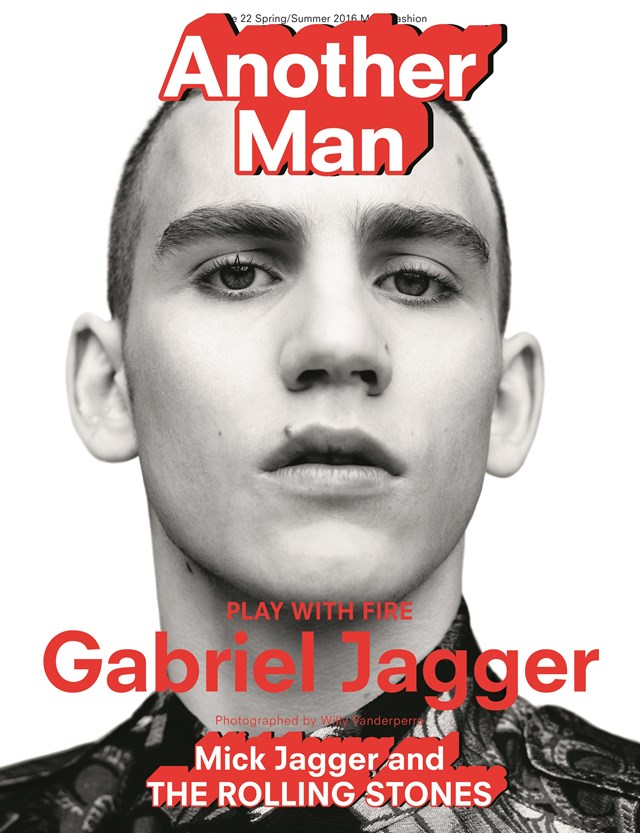

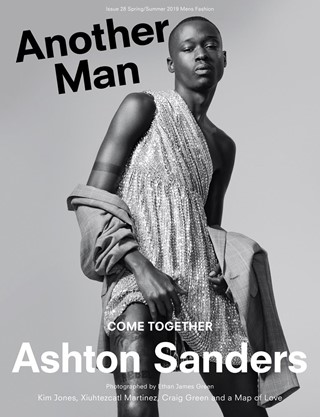

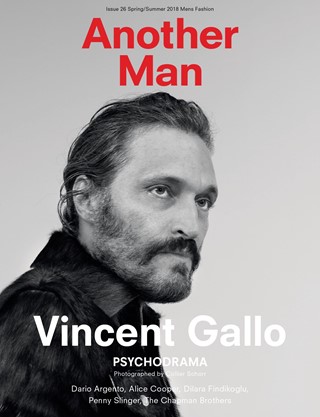

Gabriel Jagger

Mick Jagger UNDERSTANDS THE POWER OF CLOTHES. OVER FIVE DECADES PERFECTING HIS STAGE ACT INTO A MAGISTERIAL DISPLAY OF SHOWMANSHIP, ATHLETICISM AND CONSUMMATE STYLE, HE HAS AMASSED A VAST WARDROBE OF ICONIC COSTUMES. BUT THESE ARE MORE THAN JUST PIECES OF SARTORIAL ROCK’N’ROLL SPLENDOUR: THEY ARE MILESTONES ON THE CULTURAL LANDSCAPE, POWERFUL TOTEMS OF THEIR TIMES.

GRANTED UNPRECEDENTED ACCESS TO THE ROLLING STONES ARCHIVE, ANOTHER MAN PRESENTS A HANDPICKED GALLERY OF THE FRONTMAN’S MOST CHERISHED GARMENTS ALONGSIDE UNSEEN ARTEFACTS FROM THE BAND AND AUTUMN/WINTER 2016 FASHION. STARRING: Georgia May AND Gabriel Jagger; Tom Dougall FROM TOY AND Matt Saunders FROM TELEGRAM; STYLISTS Alister Mackie AND Katy England WITH HER SON Wolf; MODELS Edouard Saussac, Jake Lucas AND Tom Wells.

MEANWHILE, FROM HIS HOTEL ROOM IN PARIS, AN OFFDUTY Mick Jagger TALKS THROUGH THE OUTFITS THAT HAVE HELPED HIM SHAPESHIFT THROUGH THE AGES.

Michael Philip Jagger has been playing the part of ‘Mick Jagger’ on stages around the world for more than 50 years. It is, quite literally, the performance of a lifetime, and he’s been doing it for longer than 80 per cent of the people on the planet have been alive. That would qualify Jagger as living history if it weren’t for the fact that, decade after decade, he has been so emblematic that he has transcended chronology to become a 28-inch-hipped avatar of the eternal present.

That’s one good reason why Jagger has never felt the need to write an autobiography. His own past holds little interest for him. “I don’t mind digging up old clothes and wearing them,” he said recently, “but digging up old stories is a bore.” He makes a valid point. “Old clothes” tell the story of a performer like him more succinctly than words ever could, unless, of course, they’re the words he’s penned for the songs that everyone everywhere knows by heart. Because those songs are actually the chapters in his real autobiography, the one he doesn’t need to consign to paper. And the “old clothes” have helped give them shape and colour.

The relationship between music and clothes is a rich subtext of the huge Rolling Stones retrospective which opens at the Saatchi Gallery in London in April, whence it will undoubtedly roll around the globe, massive world tours being a Stones speciality. The exhibition is called Exhibitionism. With a title like that, you’d expect its showier artefacts (there are more than 500) to be the most striking. Of course they are, but the evolution of Jagger’s dress over the years is a perfect potted history of the band.

“In the beginning, we just wore what we had,” he says. “And we didn’t have anything, so we wore our student-y clothes onstage. Then when we first got managed, we were given what were thought of as ‘stage’ clothes, made by tailors, which were discarded half-used while we went to find our own street clothes, did them up a bit, made them individual, sewing things on them, mixing and matching. As the places got bigger, I was aware you had to make more of a statement. If you’re playing in a 1,000-seater, people can see you more, but playing in a 15,000seat arena, you have to cut more of a dash. You have to have a silhouette and a colour, and some kind of item that’s going to be noticed and followed, whether it’s a scarf or a hat. So that was the beginning of it. There weren’t people telling you what to do. You had to do it yourself.” So that’s that.

Jagger once said he’d be out of rock’n’roll by the time he was 30, which is the sort of blithe declaration it’s easy to make in your hope-I-die-before-I-get-old youth. But in those days, who really imagined a Stone would – or even could – roll past the early 60s, through the 70s, the 80s and beyond, into the uncharted reaches of the 21st century? There was simply no blueprint for such career longevity. Jagger created it, drawing the roadmap for a fearless new world of rock-till-they-droppers, defying comfy gussets, elasticated waistlines and golf as they pranced and shrank, shrank and pranced into their dotages. But he was the first, and none of the acolytes came close to matching the fascination he exercised in his prime.

“The only performance that makes it, that makes it all the way, is the one that achieves madness.” Jagger spoke those words in character as the rock star recluse Turner, a kind of Mick-but-not-Mick, in the 1970 movie called – what else? – Performance, which still ranks as his most extraordinary artefact. That movie – that scene, Turner dancing with a neon tube – transmogrified my teen existence when I saw it. “Yeah, that line was in the script,” Jagger recalls. “I don’t know who spoke it.” Given his fabulously cavalier amnesia, there’s a good chance he means those words. And, given his Dionysian stagecraft, there’s an equally good chance he knows what the line in the script actually signifi es. “Occasionally,” he concedes, “you get these almost transcendent moments in some concerts. But when you get there, it feels quite scary so you usually pull yourself back.” The fact that still happens for him, however occasionally, is as remarkable as the fear he says he feels.

But fear has always been something of a friend to Jagger. The Stones started out scaring people, their dissolute shagginess a deliberate affront to Beatle-y lovability. In their first photo shoot as a band, on May 4, 1963, they’re wearing black rollnecks and jeans that their Svengali Andrew Loog Oldham picked up on Carnaby Street. That hint of beatnik student was enough to strike terror into the hearts of wholesome family types, who had barely learned to live with John, Paul, George and Ringo’s long hair. Jagger remembers the scandal a Stone could cause by being tie-less in a restaurant. Now he admits that he can be the one mourning a decline in sartorial standards. “People just don’t dress up like they used to. I suppose in some way it seems silly of me to say I miss it because I was one of the fi rst people to try and break it down. But I kind of do. I always make jokes, ‘Oh look, there’s a man in a t-shirt,’ in a quite formal restaurant, or ‘I’m the only man in here with a jacket on.’ I make jokes about it because I’m aware of it. When people went to the theatre everyone dressed up. I don’t really miss that. But do you like going to the theatre and seeing a bloke with not very nice legs in shorts and flip-flops?”

Before you take this as further proof of the adage that we all eventually turn into our parents (maybe that should be updated to grandparents, or even great-grandparents, now that Jagger himself is one), shoehorn another image into your mind: Mick onstage in America, November 1969. He remembers the tour as a transition to a whole new level of performance. And Jagger put his look together himself. He bought the trousers at Stirling Cooper (they were an early design by Antony Price, latterly famous as the imagemaker for Roxy Music and Duran Duran, among many others). The Uncle Sam hat and long scarves came from Western Costume Co., LA’s most stellar vintage resource. But it was the motif on the scoop-necked, long-sleeved tee that stimulated the most excitement. Did it stand for omega, last letter of the Greek alphabet, the end of everything? Or was it an upside-down astrological sign, Leo, the fire sign of kings and presidents, of domination, authority and pride, all turned topsy-turvy in a time of cultural and political chaos?

In the moment, Jagger said the symbol represented infinity. Any one of those readings added to the Satanic majesty that swirled around The Stones that November. The witchy-ness peaked at the Altamont Speedway in Northern California, where The Stones played on December 6, just four days after the Manson family had been arrested further down the coast. For that performance, Jagger switched the t-shirt, top hat and scarves for a ruffled shirt and a huge black and red cape that the British designer Ossie Clark made for him. But, as Gimme Shelter, the Maysles Brothers’ documentary of the tour eventually revealed, the magic that Mick was trying to invoke was co-opted by real darkness, brought on, with ironic appropriateness, by Hell’s Angels.

Jagger remembers he was wearing boots that day. Heavy footwear, anchoring him to earth. “I never want to wear boots,” he says now, and you immediately think of his balletic skittering, never treading the boards, just flying above them. The Nureyev of rock he was, and his shoes were everything. “In the 60s, I used to wear Capezio dance shoes and Indian leather moccasins, coz they’re really comfortable,” he recalls, perfectly happy to talk about the more practical side of his past, “but they’re useless for ankle support. On a big stage, you’ve got lots of surfaces. You’ve got wood and you’ve got metal, and you’ve got stairs, lots of stuff to negotiate, and sometimes it’s a bit wet and slippery. So shoes are a very practical thing. It’s hard to find shoes that look good and do the practical work. I’m always trying to find sneakers that are going to give you support so you don’t twist your ankle. I’ve been lucky on that.”

But not so much anymore. Jagger can no longer find that ankle support. He’s still wearing his old sneakers, “which I rage about because they’re too heavy.” And when he buys new ones? “They’ve changed the way they make them so much that I have to sand the soles so I can actually do turns and spins in them. But it’s very difficult to do, because they’re so much lighter. So it’s quite a headache trying to find the right shoes. I’d love to work with a sneaker-maker. I should really be going to one, because I know they do it for tennis-players, just the way they want.” So there’s a business opportunity going begging for some enterprising entrepreneur.

But we’re not here to make life easier for Nike, or Adidas or whoever is going to strategically ally themselves with Mick Jagger’s feet when they read this. Though it does raise the issue of how he has intersected in other ways with fashion over the years. “The whole thing about fashion is that you like to see things out there that are new,” he says. But when you’re him, you’re liable to see something you wore 40 years ago cycling round again as an inspiration. “You do get clothes and you think, ‘I used to wear this, this has been recycled twice now’.”

But there are fashion images of Jagger that are indelibly his, never to be repeated, as close to iconic in the real sense of the word as rock music has ever got. For The Stones’ concert in Hyde Park on July 5, 1969, 48 hours after Brian Jones died, Jagger was dressed in an androgynous coatdress by 60s fashion guru Michael Fish. “I just bought it off the peg the day before the concert,” he remembers. “I bought a white one and a yellow one. The white one’s gone off somewhere, but Jade has the yellow one.” (Yellow has actually been something of a running theme for Jagger over the decades. It’s the colour most associated with God. Make of that what you will.)

Then there was the fruitful association with Ossie Clark. “He was very clever at thinking things through,” says Jagger. “He made those velvet jumpsuits, and that was the beginning of people making me things specifically for onstage. And Ossie made me offstage jumpsuits so I could wear them when I was travelling with Bianca. We would both wear Ossie one-pieces when we were in the airport.” Clark’s scoop-necked, rhinestone-studded jumpsuits dovetailed so well with the rise of glam rock that it’s hard to imagine there wasn’t some deliberation on Jagger’s part. Here was a new wave it was necessary to ride. He says now he was clearly conscious of the mood of the moment (the Jaggers and the Bowies teased the media with insinuations of a ménage à quatre), but the outfi ts weren’t really that thought-through. “First, it was a really comfortable outfit to wear onstage. It was like I had almost nothing on. It was really sexy and clingy, but it was very easy to move in. That was the beginning of making onstage clothes that were comfortable and not just tight street clothes. I don’t like to wear anything that feels like you’re straining in it. But I was aware that they looked kind of glammy and the outfi ts started getting more like that after that.” And those were the days when stagewear influenced streetwear. “Yeah, the late 60s and early 70s were a good period, you were very much unafraid to wear things out on the street that you were wearing onstage.”

He’s in Paris when we talk. It’s a city which could put Jagger in mind of more than his own line of footwear. Has he ever thought of doing a line of clothing? “I do sometimes, but it’s a lot of work.” He admits to extreme laziness. Right now, for instance, he’s supposed to be looking for clothes for some upcoming South American dates. But all he’s done so far is scoot once round Bon Marché, where he ended up buying a couple of Paul Smith shirts. But Jagger is fashion-savvy. “Certain designers fi t me better, like Margiela and Lanvin. There are too many alterations with other designers.”

Since the death of his partner L’Wren Scott, he’s mostly been responsible for his own on-stage styling. The South American dates are, for instance, all outside, all big stadiums. “I’m going to be on display, so I want to catch the colours. I’m the guy in yellow, so you don’t miss me when I’m in that jacket. I make quite deliberate choices about who I want to be.” Which carries us full circle to ‘Mick Jagger’, the performance. Jagger claims it liberates him. “When you’re not onstage anymore, you can shed the persona, and you can relax and calm down and be yourself. The costume helps you be the performer, but it also helps you keep your feet on the ground when you take it off.”