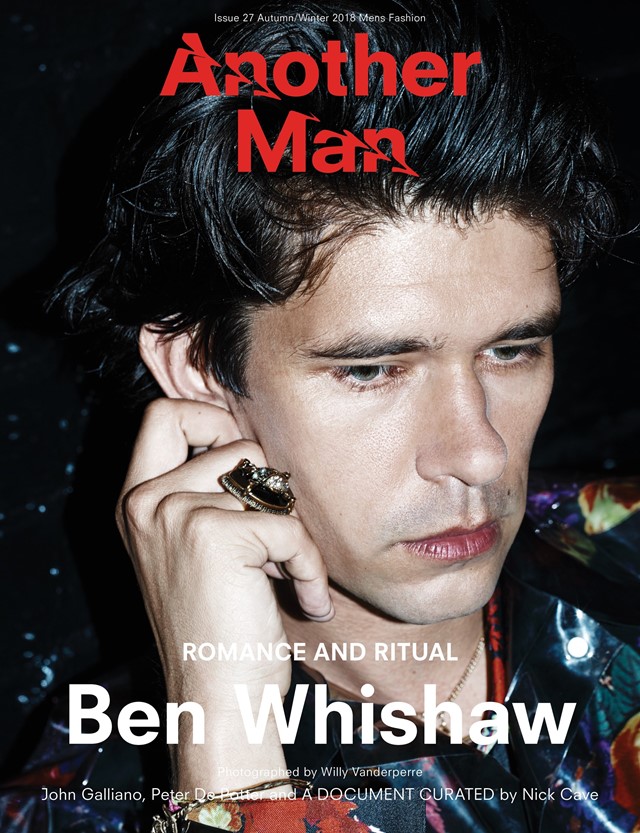

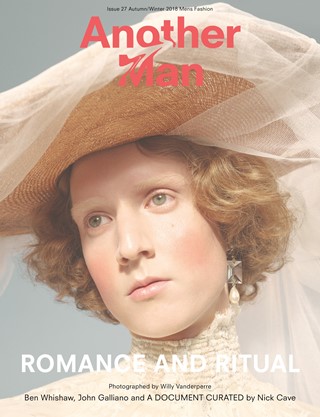

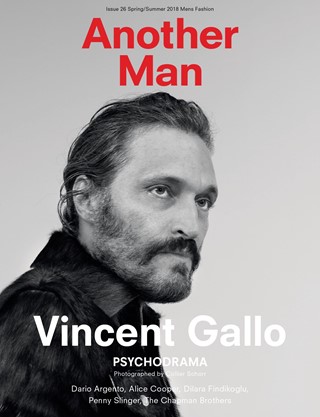

Ben Whishaw

What does Ben Whishaw love?

London. The writings of Vladimir Nabokov. One-and-a-half miniature pots of jam spread on buttered toast. And the idea of romance.

“Being romantic is sometimes given a bad press,” the actor says, eating said toast on a thick hot morning in Hackney. “Like it’s a fake thing, or an idle, dreamy perspective on something. Less frank, tough, honest... which I think is bullshit. Why is the alternative more real? Life is what you choose to make of it, how you choose to live it – so who’s to say? People need more than just the humdrum... people need other things to be fed.”

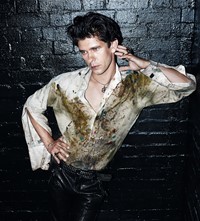

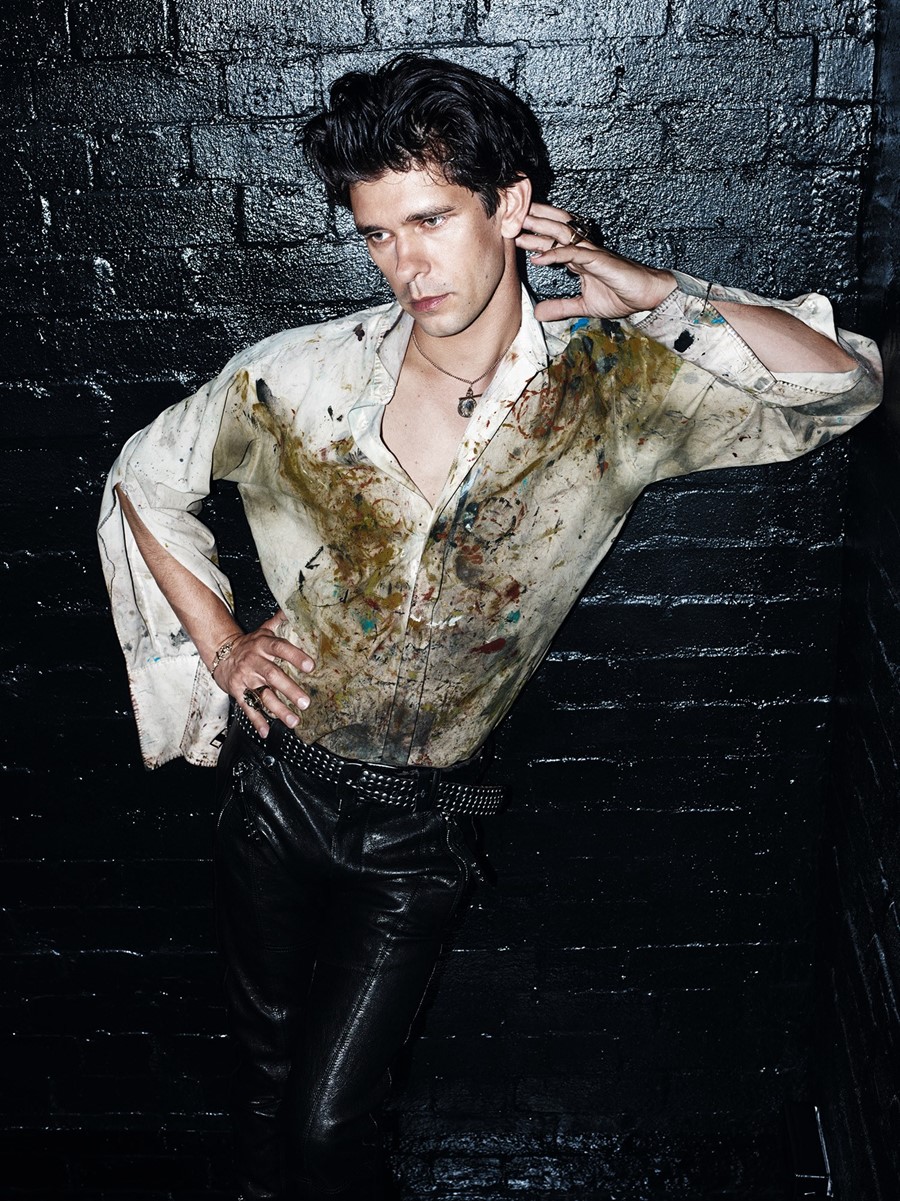

Whishaw’s best roles have always been an admixture of the darker and lighter shades of romance, coolly distilled into sharp performances of men who don’t necessarily know the ingredients that make them what they are. It’s this lack of self-awareness that the actor does so well – entering personas who are a mystery even to themselves, who brim beneath the surface of self-revelation. Jean-Baptiste Grenouille in Perfume, Sebastian Flyte in Brideshead Revisited, John Keats in Bright Star, Norman Scott in A Very English Scandal; on stage, John Proctor, Konstantin, Hamlet. All of them unable to find a place in this world which is survivable for them. They’re as much heart as mind.

It’s hard not to attach shadows of those romantic heroes to the image of Whishaw as he trudges along a petal-strewn garden path towards you, with a slight wave. The flora and fauna of Hackney City Farm’s café suit him; partly because it’s so close to his house, partly for its “ramshackle and real” qualities that evidently please him this eerily quiet Friday in July (schools are luckily not out yet). For someone so famously private – as an actor traversing mainstream and independent film with ease, he seems to hide in plain sight – sitting opposite Whishaw has an uncanny feeling of familiarity. That might be because the conversation flickers with physical mannerisms of his performances: he see-saws left and right as he speaks, as though the right phrase is in his periphery vision; when words arrive and he fixes you, his eyes are pale green pools. Whishaw’s pauses are self-assured as opposed to wary, bubbling over with thought; accompanied by a furrowed brow, or the briefest of Jean-Paul Belmondo pouts. His face moves, a lot. Most of all, as our conversation trails in different directions, he’s incredibly receptive: as though this isn’t an interview, as though we are simply here to dig out some useful truths together.

That so much of Whishaw’s acting speaks in receptivity – in the same active listening he shows as an interviewee – is testament to his uniquely unshowy presence in film. Like his characters, his light touch seems out-of-step with his age. He’s been cast as fragile men, insecure men, nerdy men (most iconically as ‘Q’, in the James Bond franchise). But there’s always been steel beneath that gauze, a determination no better channelled than in his most recent appearance on the small screen, A Very English Scandal.

“Norman is an incredible survivor, he has a kind of survivor’s energy,” says Whishaw of his character in the BBC drama, which US viewers were watching for the first time the week we meet. A kind of black comedy-of-errors chronicling the most notorious and idiosyncratic chapter in British political history, the drama recounts the rise and fall of Jeremy Thorpe (craggily perfected by Hugh Grant), a closeted gay man who was leader of the Liberal Party from 1967 to 1976. His career ended when he was charged and tried for his part in conspiring to murder his former lover, Norman Scott, the stablehand-meets-model (this is the 1960s) who had repeatedly attempted to go public with the scandalous information he had on their affair. The show’s acerbic take on the ‘Thorpe affair’, which ended with Thorpe being acquitted despite evidence of his guilt, re-tells the story for a new generation who have little knowledge about this stranger-than-fiction event – including Whishaw himself.

“To be honest, I didn’t realise how complicated it would be when I accepted the role... Everyone who I speak to who was alive then and who remembers the trial remembers how badly Norman was depicted in the press. When you’re dealing with real things, and people who have been wounded, it’s hard” – Ben Whishaw

“I had never heard of Jeremy Thorpe,” admits Whishaw. “He’s lost to history, and that’s one of the interesting things about the show: it really captures a time that has gone.” At once an unflinchingly intimate drama – with the kernel of a tender love story within it, somewhere – and a true crime thriller, the show also demonstrates how the Thorpe affair straddled wider cultural shifts that would define British modernity: when the 60s counterculture rose to threaten the establishment, and the establishment dug new trenches in response. “The trial, which is the culmination of the whole show, is at the same time as Thatcher came into office,” explains Whishaw. “I was born the next year, 1980, and then a different world starts to come to power.”

Whishaw has played living people before – he namechecks Bob Dylan in I’m Not There as a particular challenge – but the decision to take on Norman Scott was something unprecedented (he was able to meet Scott, who is alive and well; Thorpe died in 2014). “To be honest, I didn’t realise how complicated it would be when I accepted the role,” Whishaw says, a little sadly. “I have played people in the public eye. But that’s very different from taking on someone who is not a public figure, though has been observed on some platform at some point. Everyone who I speak to who was alive then and who remembers the trial remembers how badly Norman was depicted in the press. When you’re dealing with real things, and people who have been wounded, it’s hard.”

Given the immense gaps left by the prejudice of the media flurry at the time, what Whishaw does with that space is thrilling: investing the character with a tangible strength as well as a sweet naivety, and cutting loose with a sexy, troubled, ultimately redeeming depiction. Scott’s powerful speech in court, where he describes how “all the history books get written without people like (him) in”, offers a poignant moment of hope for a time when being gay won’t have to mean being sidelined. Whishaw, however, feels the show’s success lies in its evenhandedness – its sympathy for all these humans making the worst possible choices. “It’s not anti-anybody, neither does it let anyone off the hook,” he explains. “There is something humane about it. Of course, things haven’t changed and probably don’t change...”

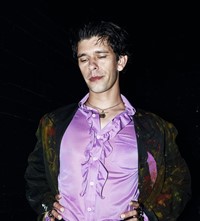

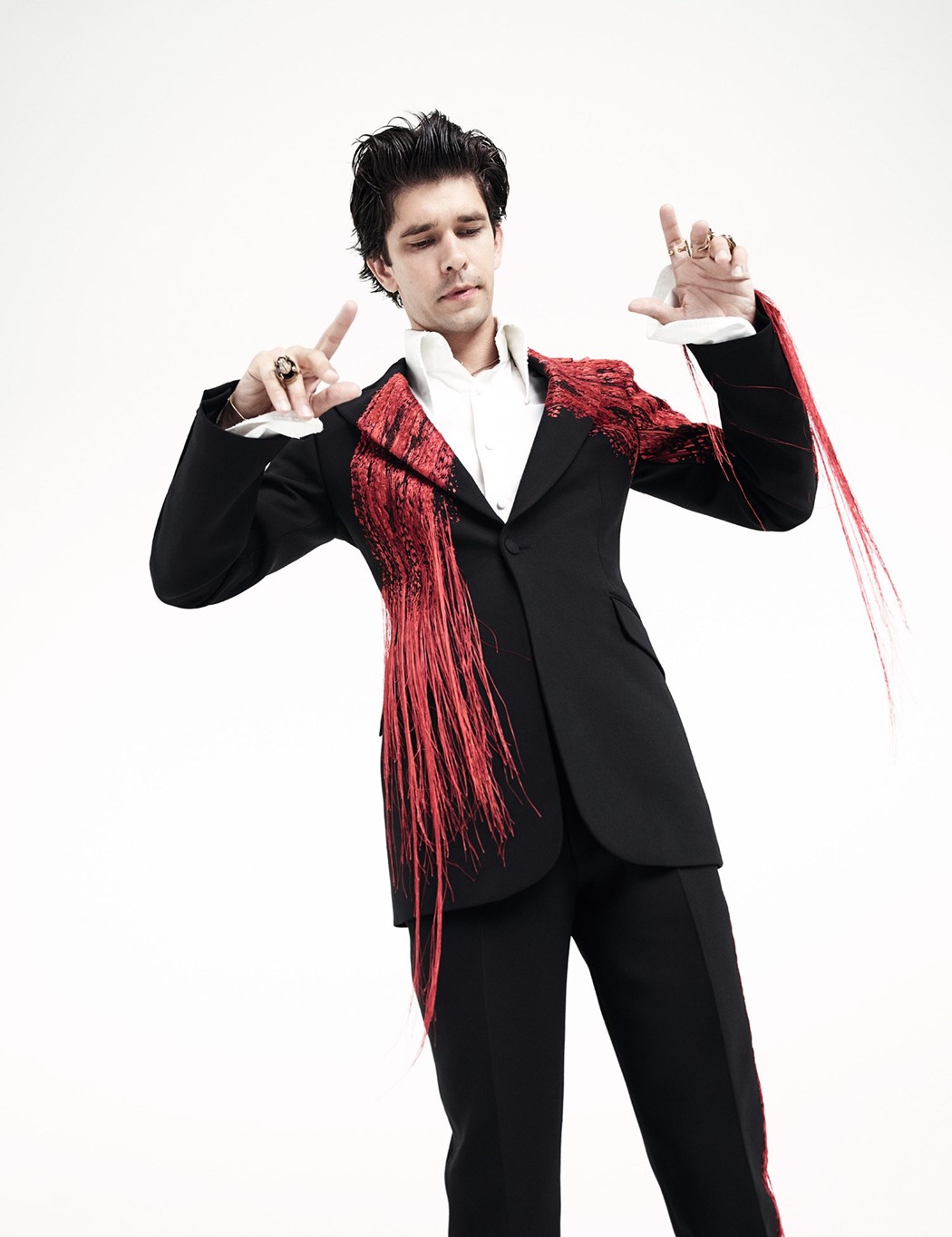

That’s a sentiment that rings true for many openly gay actors who find themselves frequently typecast. Whishaw, however, has been able to tell his own story. Married to his husband, composer Mark Bradshaw, since 2012, the actor has eschewed obviously award-baiting parts while allowing for a personal kind of activism to express itself in his choices. In Lilting (2014), he played a young man trying to connect with the elderly Chinese mother of his late boyfriend, who does not know that her son was gay; in London Spy (2015), a lonely nighthawk whose new relationship with a secretive man spirals into forbidden territory. Roles like these seem to express something of the stories Whishaw wants to tell about LGBTQ lives, which emerge like a secret fault line in his work. But for him, acting is instinct: nothing to do with his real life, everything to do with his fundamental beliefs. “The older I get the more I really feel that acting is my expression,” he says. “That there must be a reason why I need to get these things out; these kinds of stories and these kinds of characters. For me, it’s never straightforwardly, ‘This happened to me, therefore I can do it’.”

“The older I get the more I really feel that acting is my expression. That there must be a reason why I need to get these things out; these kinds of stories and these kinds of characters. For me, it’s never straightforwardly, ‘This happened to me, therefore I can do it’” – Ben Whishaw

“I’m really interested in how you can know something, even though you don’t know it,” he continues, musing intensely on an empty spot three seats along. “How you can inhabit something, even though you’ve never experienced it. There’s something that we share that we don’t know: a collective human consciousness, or past lives, or literally in our genetics. It’s bigger than the circumstances of your own life. I feel that when I’m acting. There’s something else that comes in. It’s like dreams – where are they coming from? They come from somewhere else.”

Continuing the thought, Whishaw draws out the parallels between his compulsion to act and the compulsion to love: both involve a desire to make the unknown known, but sparks are only given off in the pursuit. The moment you become self-aware, it’s impossible. “When I was younger, starting out in acting, I was obsessed with love and trying to find it,” he smiles. “But I feel we’re not living in very romantic times, don’t you think?”

“Because we’re not living in a time where people value not knowing something,” he expands, citing the social media platforms that he, publically at least, avoids. “They value everything being laid out and advertised. And that’s how people get a sense of self worth – of being seen and being known. The demonstration of your individuality is everything.” For Whishaw’s part, he values the mystery at the heart of all things, and trusts in what nature has in store for him: he only knows that winter is horrible and summer will eventually come, a theatre performance might go terribly but tomorrow, you do it again. “Everything is cyclical,” he says. “We wake up and we go to sleep, but I don’t find that hopeless or nihilistic.”

It’s on stage where Whishaw feels he has grown the most as an actor; where he first appeared in the public consciousness as a wunderkind Hamlet (at the Old Vic, in 2004), and has appeared regularly since. But while he blazed onto the boards as an instant prodigy, as the actor matures, he feels he only gets better. “For me it’s really important that artists are allowed to grow,” he says. “Not to say that Timothée Chalamet isn’t amazing. I get that. That kind of blithe ignorance and innocence is very exciting – raw, and powerful.”

Before stage and screen, Whishaw’s first love was London; having grown up just outside, like most children of the Commuter Belt, he feels “very passionately” about the city. His next project is as London as it comes: a bitingly satirical film adaptation of Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield by provocateur Armando Iannucci, which he is mid-filming when we meet. “It’s very much Dickens but it’s very much Armando too,” he enthuses. “And joyously not very faithful to the book. I’m playing Uriah Heep, the archvillain. I love Dickens and I love his love of people, eccentricity, and that celebration of human oddity – just gorgeous. But what we’re exploring is what is it about this world – this society that these people are living in – that makes them do the things they do?”

The Iannucci project appeals to Whishaw’s gleefully dark streak, which extends to the confrontational reading on his bookshelves. Today he takes Nabokov’s Speak, Memory and Edouard Louis’ latest book History of Violence out of his Fjallraven backpack (the latter, he says, “writes with this amazing honesty and fantastically uncensored, brutal, beautiful clarity about things”.) For Whishaw, “art should be transgressive. It should push, and be uncomfortable, and offer another perspective on things. We’ve got to protect that. Otherwise…” He needn’t fill in the gap: with today’s post-Trump political chaos and ever-narrowing media filter bubbles, making art which breaks through held opinion is more vital than ever. “We mustn’t be allowed to be smoothed away. We don’t all have to agree. I feel very strongly on this at the moment – difference is really great.”

When nuance, ambiguity and the value of taking one’s time is overtaken by a culture obsessed with seeing things in black and white, going to the cinema becomes close to a political act. Where else do you have solitude-in-community, switched-off phones and new worlds to wash over you and hold close? Endless opportunities to fall in love. Whishaw knows this – and he’s happy to scramble around in the dark like the rest of us. “Sometimes the characters feel more real than my life, if that makes any sense,” he says. “Because you can see them. They’ve got a beginning, and an end.”

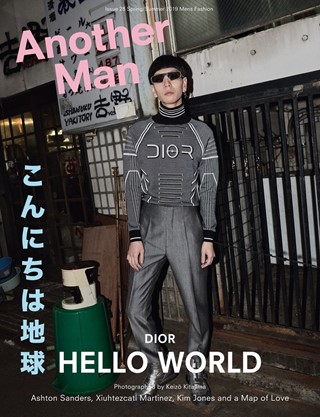

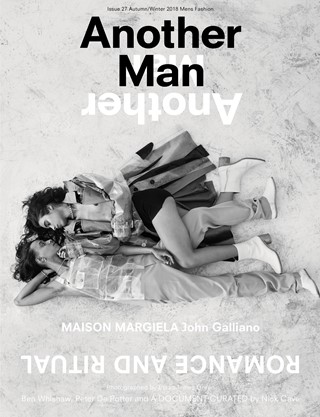

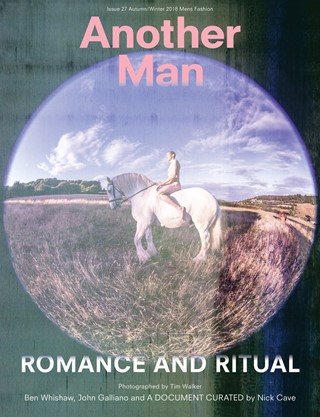

The A/W18 ‘Romance and Ritual’ issue of Another Man is out now. Buy a copy here.

HAIR Anthony Turner at Streeters MAKE UP Lynsey Alexander at Streeters MANICURE Adam Slee at Streeters using CHANEL La Base Protective And Smoothing and CHANEL La Creme Main SET DESIGN Emma Roach at Streeters PHOTOGRAPHIC ASSISTANTS Romain Dubus, Robert Wiley, George Eyres DIGITAL TECHNICIAN Henri Coutant STYLING ASSISTANTS Vincent Pons, Ruairi Horan, Kiran Sanghu HAIR ASSISTANT Claire Grech MAKE UP ASSISTANT Phoebe Brown SET DESIGN ASSISTANTS Camila Perna, Joseph Burke PRODUCTION Ragi Dholakia Productions POST PRODUCTION Triple Lutz