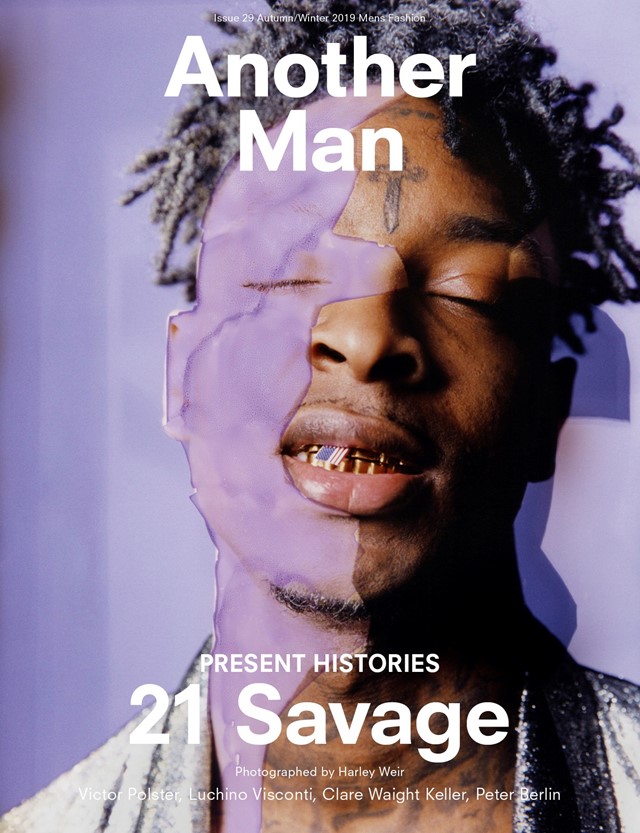

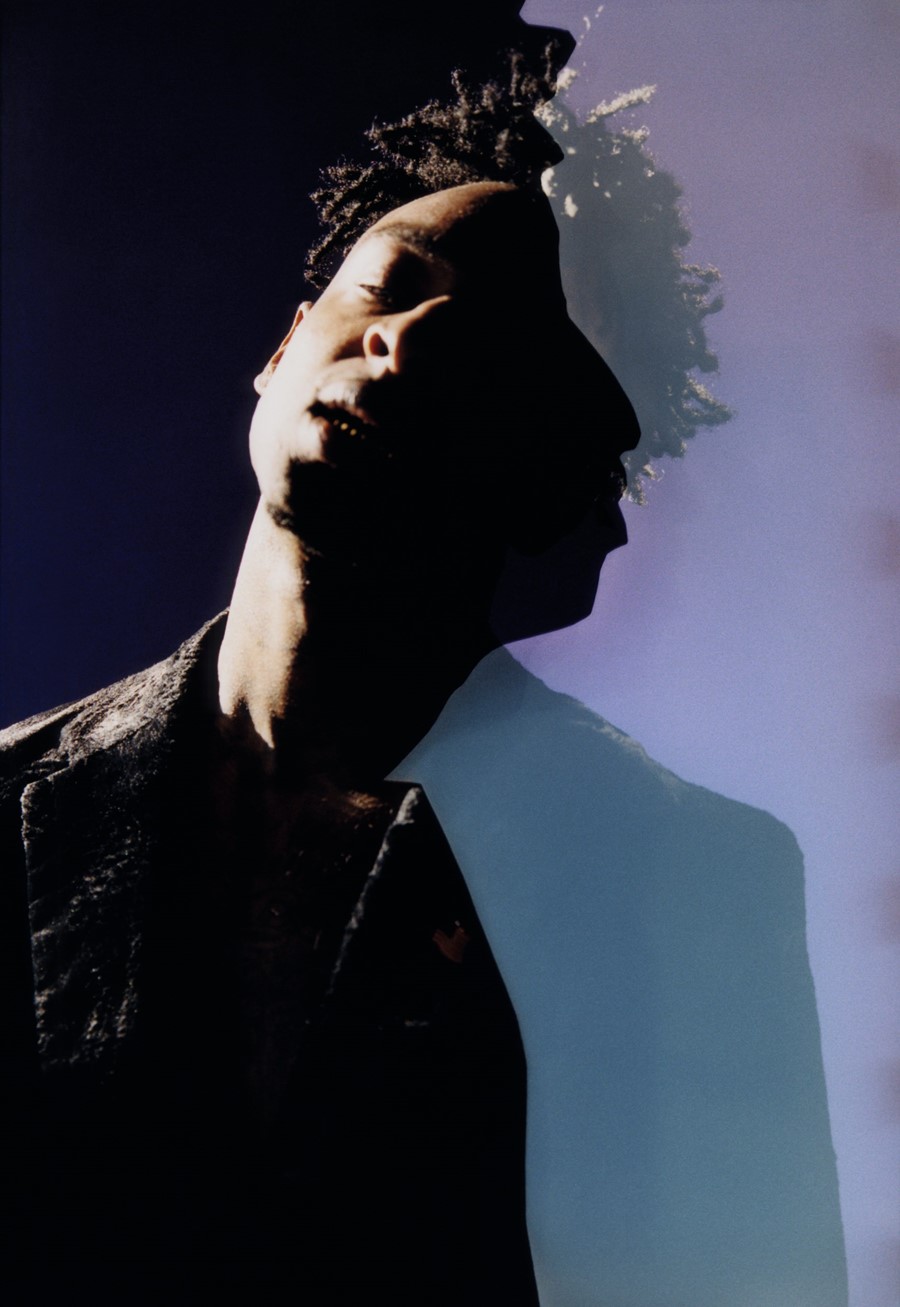

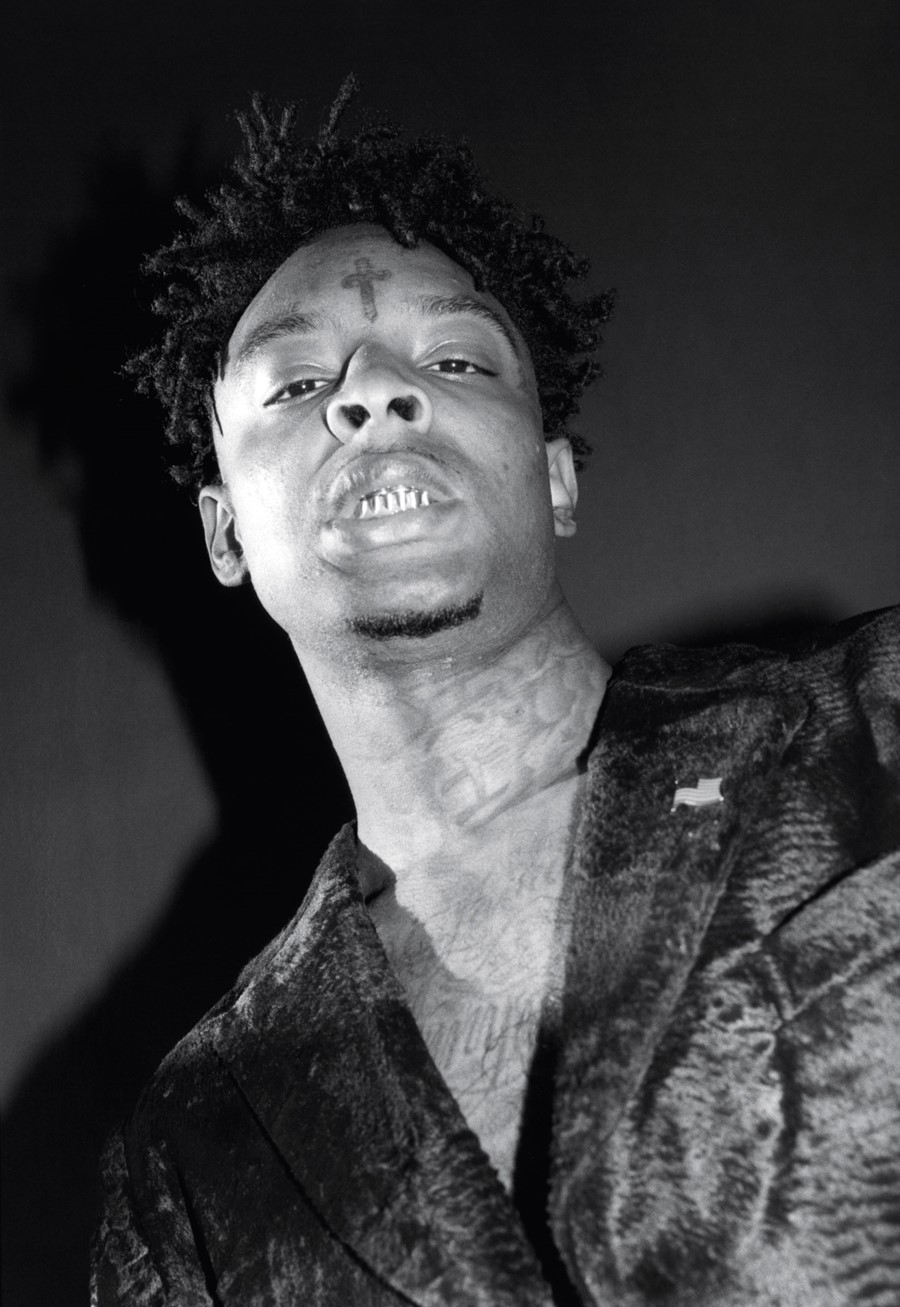

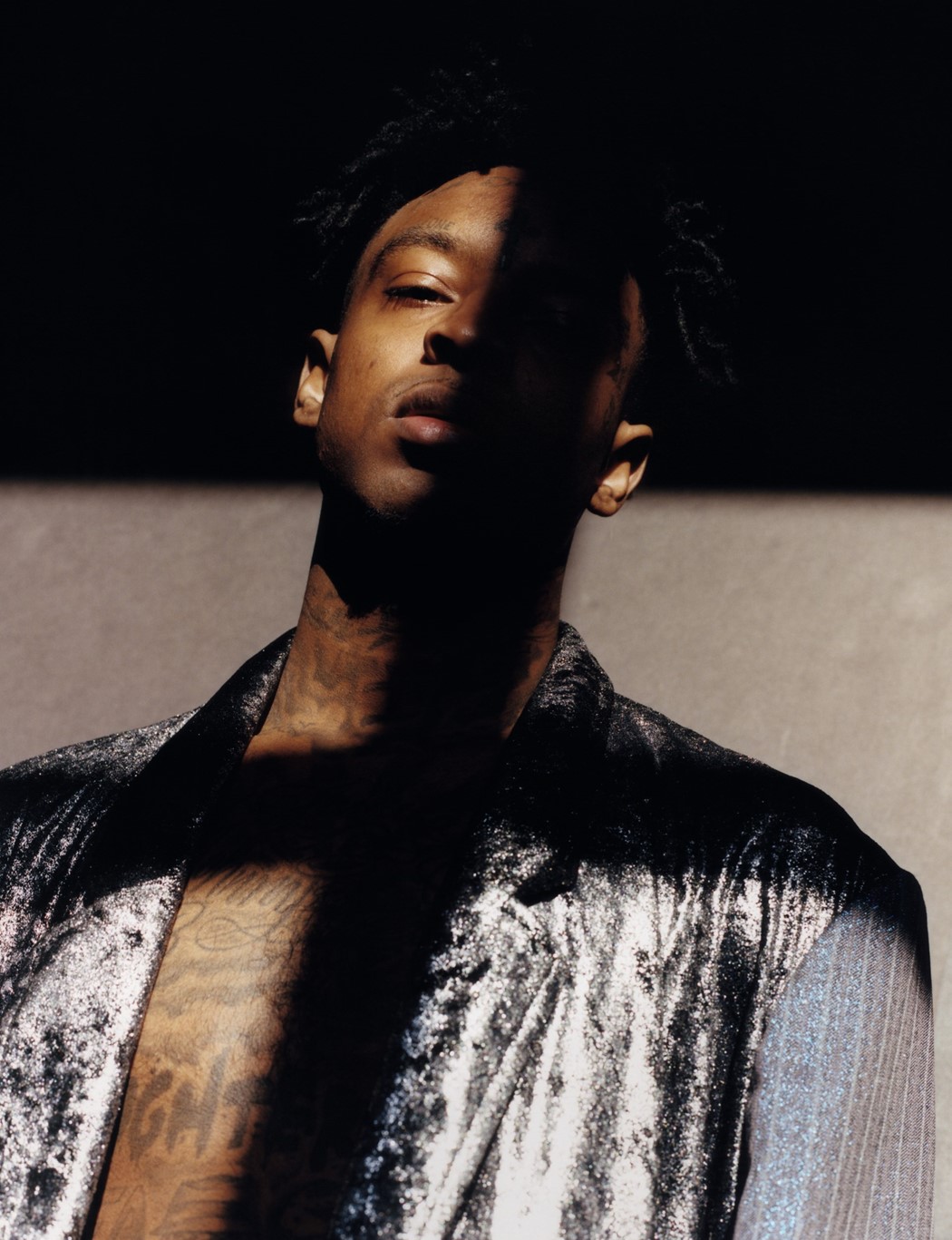

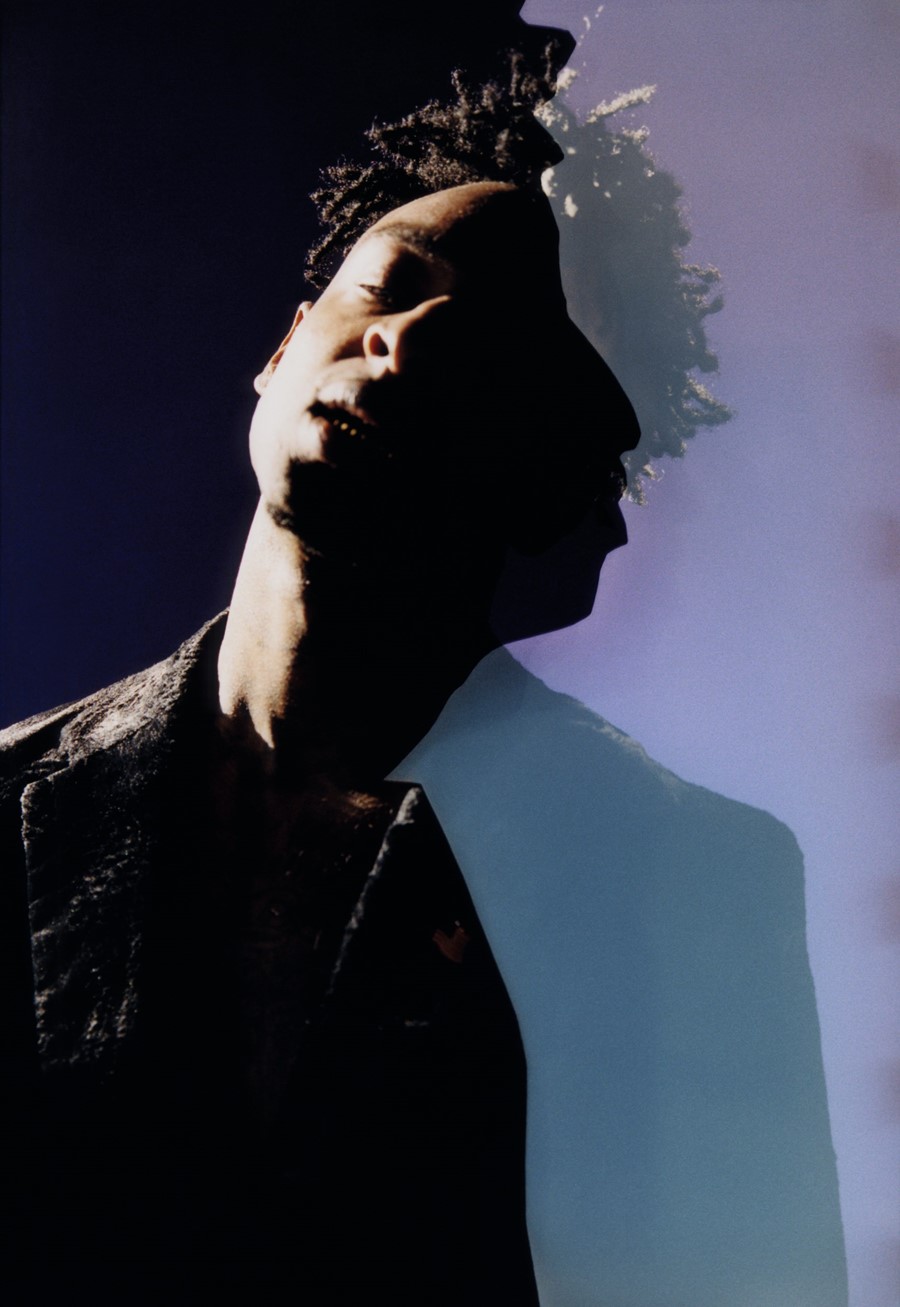

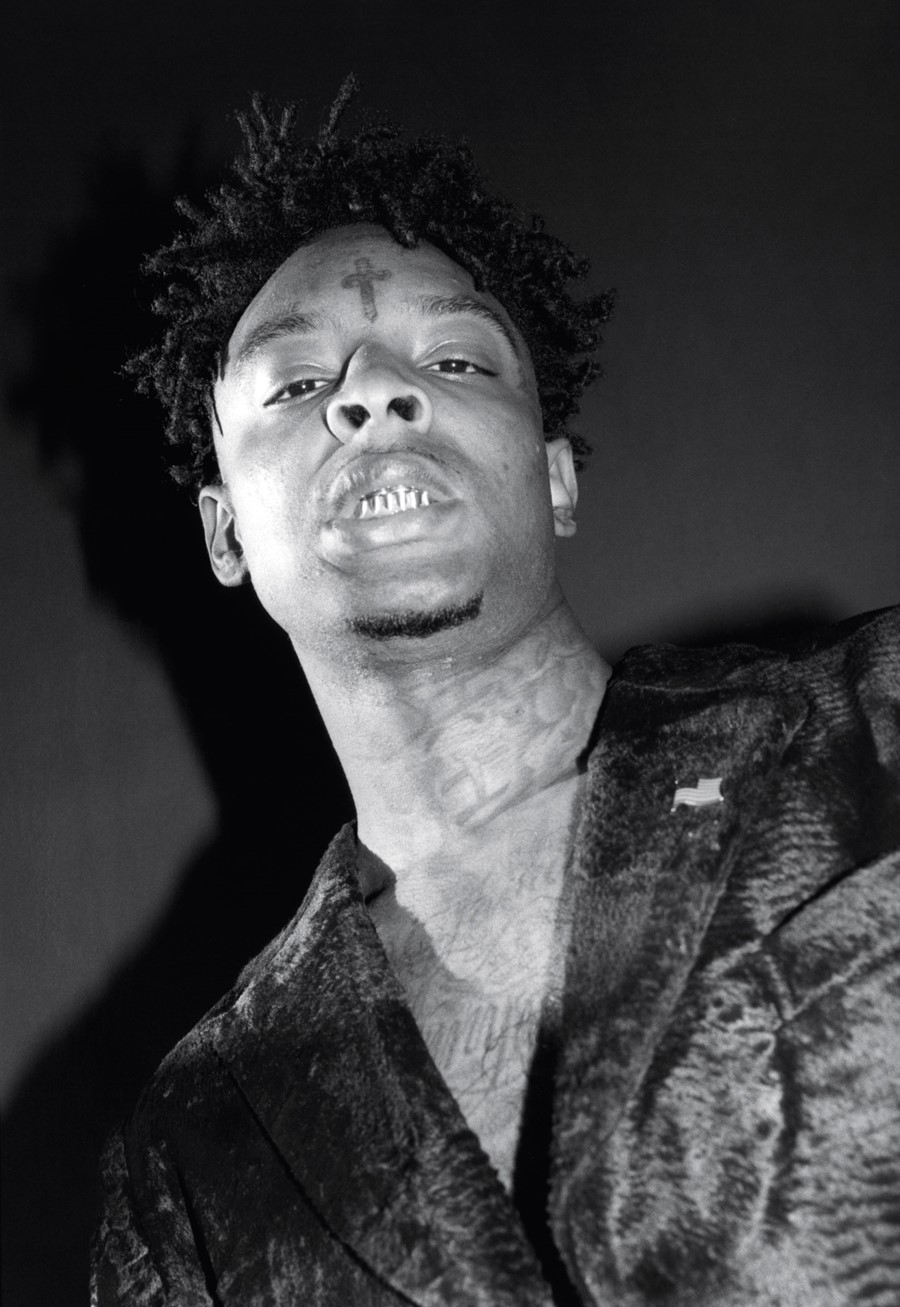

21 Savage

- TextThomas Gorton

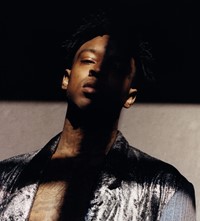

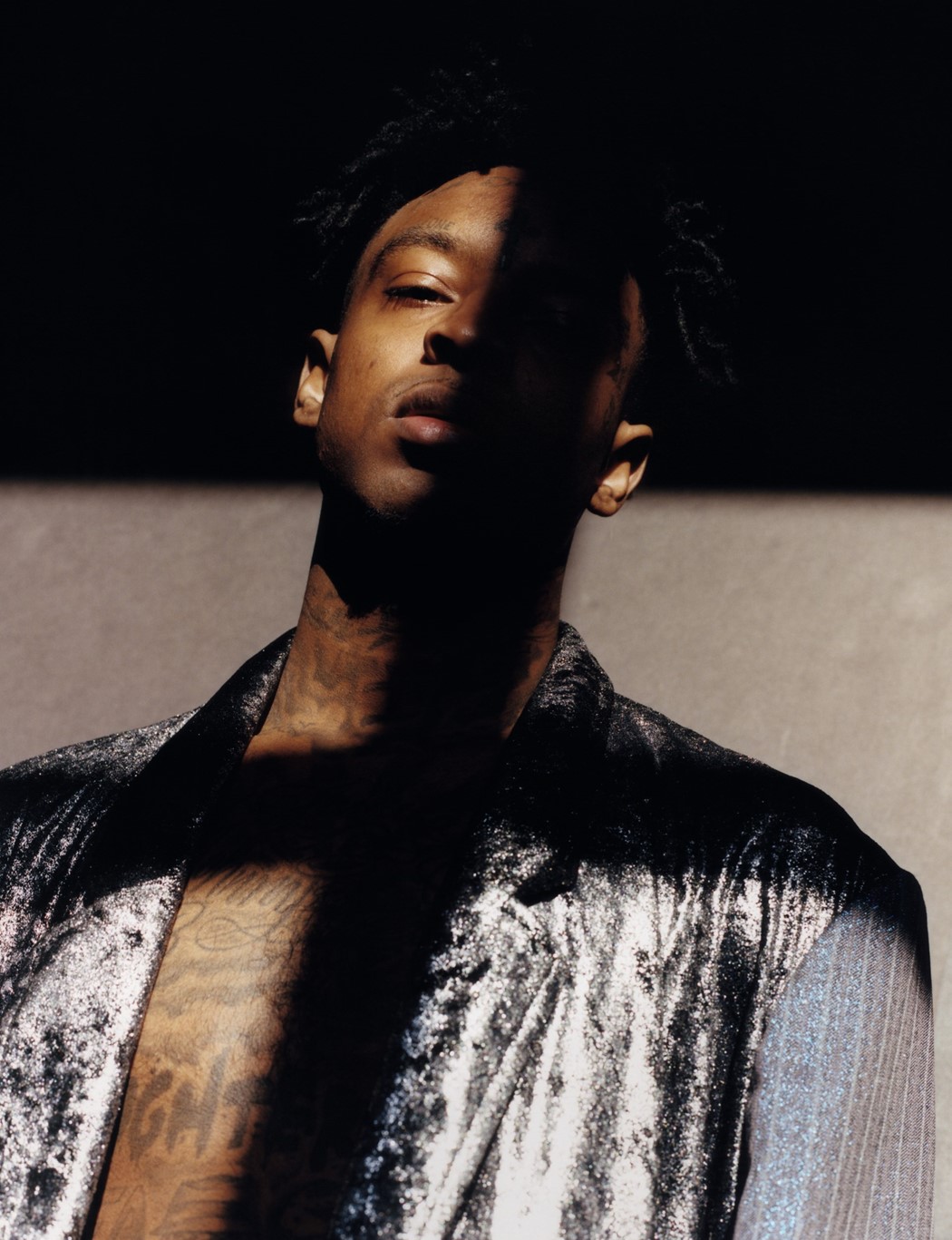

- PhotographyHarley Weir

- StylingEllie Grace Cumming

Issue 29

2019 HAS BEEN A ROLLERCOASTER YEAR FOR 21 Savage.

THINGS STARTED WELL ENOUGH FOR THE ATLANTAN SUPERSTAR WITH HIS SOPHOMORE ALBUM IN THE TOP SPOT OF THE BILLBOARD 200. TWO MONTHS LATER HE WAS ARRESTED BY ICE AS AN ILLEGAL ALIEN AND INCARCERATED, FORCING HIM TO MISS A HEADLINE PERFORMANCE AT THE GRAMMYS.

STILL ON BAIL BUT BACK ON THE ROAD AND IN THE STUDIO, THE 26-YEAR-OLD IS A CHANGED MAN. GUARDED, SUBDUED AND DEFINITELY NOT IN A HURRY TO PICK UP THE PHONE, HAS TRAP’S FIREBRAND BEEN DIMMED?

I eventually speak to 21 Savage on one of his rest days in the midst of a 20-date American tour. It’s the fourth try, after numerous attempts from his management to conduct this interview via email. The line is crackly, Savage sounds far away, distant. Most of all, he sounds tired. His management are on the line, only occasionally making their presence known to request that some of the pre-approved questions are skipped, and that our time is up. But however remote he seems, over the echo and delay of the cross-continental connection we are, eventually, talking. The artist – one of the biggest rappers in the world – is present.

It is no surprise that he’s exhausted. Beyond the strain of touring America, the 26-year-old Atlanta-raised 21 Savage, born Shéyaa Bin Abraham-Joseph in Plaistow, London, was arrested on 3rd February, 2019, by ICE agents, who accused him of unlawfully staying in the US after his visa expired in 2006. In an interview with Good Morning America, Savage recalled the glare of the helicopter circling overhead, the guns, the blue lights, and one of the agents saying “we got Savage”. He was in jail for nine days before being released, and it remains an ongoing legal situation that dictates what he can and can’t say. “I’m not trying to say anything to provoke ICE,” he says. “I’ve still got a family in America and I have a case that could get me kicked the fuck out of America away from my family.” Some, including his lawyer and congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, believe the arrest was retaliatory, a response to Savage performing an alternate version of his hit single a lot on Fallon that included the lyrics “the gas was off, so we had to boil up the water. Been through some things so I can’t imagine my kids stuck at the border. Flint still need water. People was innocent, couldn’t get lawyers.” Four days later the rapper, whose latest album I Am > I Was hit No.1 in the Billboard charts, was in a cell.

US Immigration and Customs Enforcement is a defining image of Trump’s America, an aggressive federal unit who in August carried out their largest raid in a decade, rounding up 680 undocumented workers at sites across Mississippi. Families are being torn apart, children detained, tensions heightened.

Another defining image of modern America is 21 Savage, a man who grew up tough in Atlanta, was banned from every school in his district in 7th grade for bringing a gun to school, survived six bullets on his 21st birthday, lost his best friend in the same attack, and became a globally-recognised, Grammy-nominated, totemic trap artist, a godfather of the world’s most influential genre.

His arrest represented the apex of the American Dream and Nightmare colliding. Pop culture icons like Cardi B, Killer Mike and Meek Mill – who has experienced his own brutal treatment at the hands of the law – all spoke out in support. Inside his cell, he visualised freedom, his mother, and waited. On the outside, people questioned that increasingly important but ever elusive attribute – his authenticity. Wasn’t he meant to be from Atlanta? Savage didn’t say he was British! Twitter exploded, and much to the frustration of his friends he became a meme, something that the rapper said he appreciated at the time. Knowing he was on people’s minds gave him comfort, and he has little interest in people questioning his legitimacy as an Atlantan. “The streets know where I’m from, the people who I was caught up with know where I’m from, my momma know where I’m from,” he says. “I don’t really care what anybody else thinks. They can think what they want to think.”

Difficult connection aside, this is not an easy interview. There’s a defiant reticence to his answers, a wariness that dominates the conversation, and indeed this whole process. There is however something completely endearing about his childlike closedness. I ask him who he considers the best artist in the world? It’s not a particularly interesting question, one that perhaps doesn’t demand an interesting answer, but I threw it in to placate the pre-approval process. He will absolutely not entertain the idea that there is a better artist in the world than himself.

Who do you consider the best in the world if it wasn’t 21 Savage?

“I would say me.”

But if you couldn’t say you?

“There’s no way that I couldn’t say me. I would still say me.”

Who do you see as your competition?

“I don’t have any competition. I don’t really care about other artists. I care about me.”

After the call, a member of his team WhatsApps me to apologise for his shortness, and agrees that he’ll answer follow-up questions over email. Ten are sent, but the answers never come back.

He might not seem interested in this interview process, but Savage is by no means an apathetic artist. He’s a philanthropist, and one who has repeatedly given back to the streets he grew up on in a way that separates him from his peers. Since 2016 he’s hosted the annual Issa Back to School Drive, an initiative that helps kids out in Atlanta with school uniforms, stationery and haircuts. (‘Issa’ refers to ‘it’s a... ’, a term he coined in a 2016 interview when asked what the tattoo on his forehead was: “Issa knife,” he replied. It’s now slang used by kids from Atlanta to Acton.) This year – just days after being released by ICE – he launched a financial literacy programme called the 21 Savage Bank Account Campaign, aimed at advising kids on how to manage money and steer clear of aggressive credit card companies.

“It’s a good feeling to be able to do the stuff that I do,” he says. “It’s very important to me because I never had anyone giving me anything from school growing up. I never saw any artists do that type of stuff when I was growing up. Nobody came back or gave away anything. People barely do it to this day. It’s important for me because they support me so I feel like I should support them too. It makes me feel good because I know my influence can change the cycle. That kid’s kid might have a better chance, and so on and so forth.”

Savage has also been outspoken about gun violence – another defining image of modern America – but now cannot imagine a world without firearms, despite having called for them to be removed from the planet back in 2016. “There’s never going to be a future without guns, there’s always going to be guns,” he says. “If they were never made in the first place, we wouldn’t have these problems, but it’s too late now. There’s too many guns made. All we can do is try and control who can get guns.”

Talking about other people, or other issues, is when Savage seems to feel most comfortable and is most forthcoming. He’s immensely proud of his three children, and he’s determined to create a bright future for them through his art. But as soon as the conversation moves to him, his work or his interests, or even his past, he shuts down. He moved to Atlanta from London aged seven, but remembers little of his life in England beyond playing Tekken with his cousins in his grandma’s house. Neither does he recall any details about returning for a month for an uncle’s funeral in 2005, and doesn’t have any affinity with UK music – although he comes alive at the idea that he might be misquoted as disliking it. “If you post this in a magazine and say I don’t care about it, that doesn’t sound the same as me just not listening to it,” he says. “It sounds like I’m dissing it. I know some of the people and the big names but I don’t really listen to it. I don’t really listen to rap like that anyway. I listen to a lot of RnB.”

Over this glitchy transatlantic line, Savage sounds like a sensitive person quietly wrestling with conflict, a quality that comes through in his music. Case in point: the opening of a lot starts with the words “I love you”, a beautiful soulful sample taken from a song of the same name by a group called East of Underground, a band formed in the army during the Vietnam War. From there, Savage ruminates on money, cheating, lying, crying, infidelity, violence. It’s a lot.

Owing to his detention by ICE, Savage was unable to appear at the Grammy awards with Post Malone, and perform Rockstar, the number one single that he features on, and which earned him two Grammy nominations. Despite such a high-profile arrest, artists stayed quiet at the awards show. In fact, it was only Ludwig Göransson, a Swedish producer who worked on Childish Gambino’s This is America, who acknowledged 21 Savage in a speech. Post Malone was photographed wearing a 21 Savage T-shirt backstage. Savage says the silence didn’t bother him. “Nobody can stand up for me,” he says. “I can stand up for myself.”

Rockstar is an archetype of the decade’s braggadocious pop trap template, a minor-key banger that details the emptiness of excess, while simultaneously boasting about the luxury of finding endless sex, drugs and dollar bills boring. No one seems truly happy. And it’s something that sticks with me as I consider the machinations of making this interview even happen at all, wading through a team that surrounds a team surrounding an artist, who seems trapped in it all.

We live in a safety-first world of celebrities interviewing each other, an information age where any soundbite becomes a story, and a culture of cancelling. Are we all afraid of each other now? These past ten years will be remembered for many things – Donald Trump, Instagram, the climate crisis, and perhaps the death of the pop star interview. Which in this particular instance is a shame, as 21 Savage doesn’t have nothing to say. He has a lot.

HAIR Kenny Williams SET DESIGN Stacy Suvino with The Spin Style Agency PHOTOGRAPHIC ASSISTANTS Gwen Trannoy, Drew Leach STYLING ASSISTANTS Jordan Duddy, Isabella Kavanagh, Alex Assil SET DESIGN ASSISTANT Fatiyha Johnson with The Spin Style Agency PRODUCTION Connect the Dots SPECIAL THANKS Art Partner