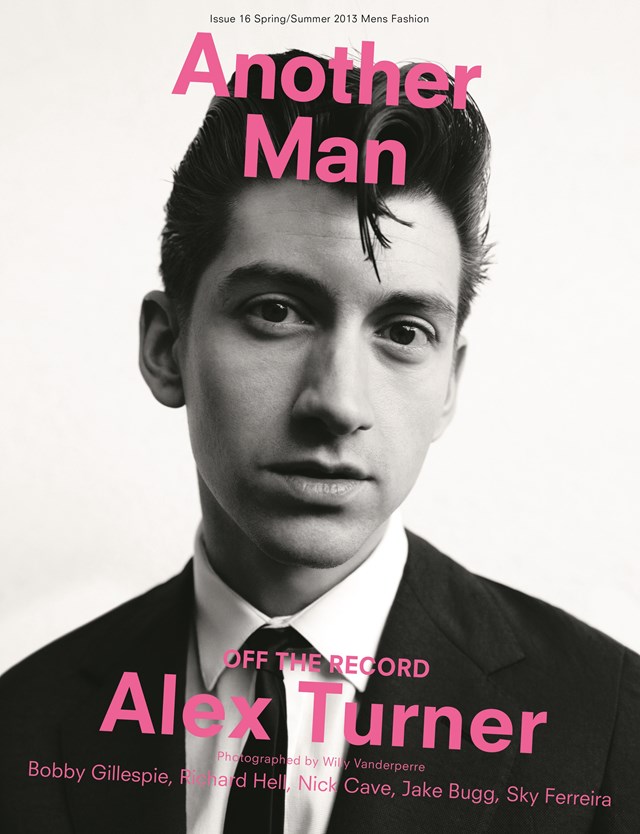

Alex Turner

The Musso & Frank Grill on Hollywood Boulevard is the oldest restaurant in town. According to the well-thumbed menu, it’s been “proudly serving Hollywood since 1919”, four years before those giant iconic white letters first appeared on the hillside behind it. Inside, not much has changed since Joseph Musso and Frank Toulet opened the doors to their dusky eaterie: oak-beamed ceilings, scarlet leather booths, mahogany walls and staff dressed in pristine red blazers.

Rudolph Valentino used to drop in here for the spaghetti bolognese, Charlie Chaplin for the boiled lamb with caper sauce, Gary Cooper for the tenderloin steak and baked potato, and Ginger Rogers for the rum dessert cake. F Scott Fitzgerald, Raymond Chandler (who name-checks Musso’s in his noir classic The Big Sleep), Ernest Hemingway, Orson Welles and Charles Bukowski were all regulars at the bar. And, if Louie – who has been taking orders since 1957 – is to be believed, it’s where, one unforgettable night, Marilyn Monroe sipped a bone-dry martini, swivelled round on her stool and made an unsuccessful pass at him.

It’s late afternoon on a Friday and, apart from a middle-aged couple on the other side of the room, engrossed in the early flush of an affair, the restaurant is empty. But, according to Arctic Monkeys frontman and Musso’s regular Alex Turner, it’s a good time to soak up the Old Hollywood atmosphere – as well as the bottled Newcastle Brown Ale on offer. “It’s great how they serve this here,” he says, taking a man-size swig and sliding back in his corner booth. “It’s a nice little reminder of home.”

It’s been almost eight years since the Arctic Monkeys – four scruffy Sheffield scamps with an unstoppable swell of homegrown support – hijacked the airwaves with their stomping breakthrough single “I Bet You Look Good On the Dancefloor”. At the time, a bolshy Turner grumbled, “Don’t believe the hype,” but nobody listened. He was promptly heralded as the voice of a generation, a master of witty and poetic lyrics, and, quite possibly, the saviour of British guitar – even Chancellor Gordon Brown, in his bid for Number 10, got on the bandwagon. Their debut album, Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not, became the fastest selling in UK history.

Vowing to become “better not bigger”, Turner and his bandmates – Jamie Cook (rhythm/lead guitar), Nick O’Malley (bass guitar/backing vocals) and Matt Helders (drums/backing vocals) – brushed off the pressure to repeat a winning formula and went on to produce three singular and, at times, challenging albums; and, in the process, became both better and bigger. 2007’s Favourite Worst Nightmare, 2009’s Humbug and 2011’s Suck It and See all went straight to No.1, making them only the second band in history to debut four albums in a row at the top spot. Somewhere in this gruelling schedule of headlining tours and studio sessions with the Monkeys, Turner also found time to work on The Last Shadow Puppets, a side project with The Rascals’ former frontman Miles Kane, and score the coming-of-age hit film Submarine.

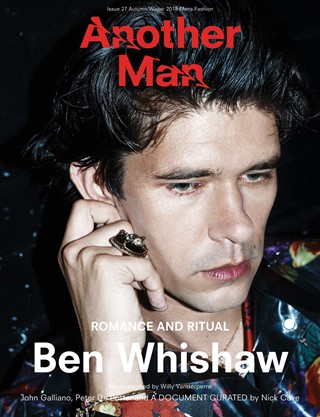

Fast-forward to today and, after a year-long spell in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, a sell-out North American tour with the Black Keys and a head-to-toe rockabilly makeover, Turner and the Monkeys have set up camp in Los Angeles and started work on new material. Thankfully, the frontman shows no signs of forgetting his roots. He proudly shows off a Sheffield rose tattoo on his left forearm like it’s a powerful talisman – “Well, I wasn’t going to have some Chinese symbol, was I?” he laughs, his thick Yorkshire accent undiminished by four years in the States. He also constantly twiddles a ring on his right little finger emblazoned with the words “Death Ramps” – the childhood nickname for the local hills where the Arctic Monkeys used to ride their BMXs.

Still only 27 years old, any cocky bravado in Turner has mellowed into a relaxed confidence. He seems comfortable in his own skin and, finally, with his place in the dizzy worlds of music and fame. In conversation he’s thoughtful, self-deprecating and open; worried about sounding “really boring”, he stops himself midway through the ongoing saga of a rogue humming in his home stereo (neither his father, a former physics teacher, nor a studio engineer have solved the problem yet). The only time he slightly falters is when asked where in LA he lives – “Errr,” he splutters, “we’re all sort of staying around the… kind of near the canyon area”. (A door number and zip code weren’t expected).

Dressed in a black leather jacket, black t-shirt and jeans, and crowned by a magnificently maintained quiff, he looks like a young, doe-eyed George Harrison from The Beatles’ Hamburg days in the early 60s. The similarity was startling when, last summer, the Arctic Monkeys performed a barnstorming cover of The Fab Four’s “Come Together” at the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games. “Aye, that were a boss night,” he says, as if remembering a Saturday drink at his old Sheffield local, The Grapes.

He’s right, of course, but that warm July evening in 2012 will also prove to be a watermark point in the story of the Arctic Monkeys. With the eyes of the world on them and Paul McCartney watching from the wings, it was the moment they rightfully claimed the British rock crown. And, as their magnetic frontman swung his Les Paul guitar on to his right hip and sang, “Got to be a joker, he just do what he please…”, it was the moment Alex Turner the icon came of age.

Why the move to Los Angeles?

It’s a bit of cliché but this town is built on rock’n’roll so the best studios and equipment are here. It’s just one of these places where records have always been made and where they’ll continue to be made forever, probably. Well, that and the fact that the sun always shines and you can ride your motorcycle in December.

How does it feel having the band together again in one place?

We hang out more than ever so it’s kind of like we were in the beginning, back in Sheffield. For a while things got a little fragmented because I’d be off in New York or wherever but it’s great now because we can work on music together every day. It’s been a long time since we’ve made a record that way.

Do you worry that Tinseltown could soften your Yorkshire grit?

(Laughs) No chance! I’m not going to start writing Californian songs about highways and palm trees. Someone told me a thing about LA that’s really stuck with me: ‘You sit by your swimming pool and fall asleep with your Pina Colada and then you wake up and you’re 50 years old!’ We’ll have to wait and see but I don’t think that’s going to happen to me. I think, as a reaction to most guitar music out there, which is really bland at the moment, the opposite will happen. Who knows, maybe I lost my edge five years ago? But you’re fucked if you have to start trying to keep an edge – you just have to keep sight of why you wanted to be in a band in the first place.

And why was that?

We lived in this place called High Green, which is on the outskirts of Sheffield, and this town called Chapel Town was the next metropolis and we’d go and watch this local band down there. It was six bus stops away, which when you’re 15 feels epic. I remember there was this one night – there were probably only ten people in the crowd – but it was the coolest thing I’d ever seen. It kind of showed me another world, another way to live.

Pulp, Def Leppard, The Human League, Joe Cocker…Why do you think Sheffield has produced so many musicians?

And all with such different sounds... I really don’t know. Richard Hawley – another great Sheffield musician – put it to me that Liverpool has produced lots of different bands but they all have a Liverpool sound, the same thing with Manchester, but Sheffield? I mean, we don’t sound like Pulp, we don’t sound like Def Leppard and we definitely don’t sound like Human League…

And there’ll be new Sheffield bands coming up that sound nothing like the Arctic Monkeys.

Definitely. In fact, there’s another band from Sheffield now that are a big deal in the hardcore scene, they’re called Bring Me The Horizon. It’s fucking mad loud music, lots of screaming. I mean, I respect it – it’s kind of awesome – but it’s not my thing… Actually, the lead singer even went to our school, I think he was in the year below. Anyway, it could not be more different to what we do but we’re all from the same nest.

So, you never felt part of a scene?

We always rejected the notion that we were part of any scene. We were like, ‘Fuck you!’ to everything that was outside our world and our group of mates – I don’t know why that was. I was just writing lyrics to make friends laugh; it was literally for those ten people in our little clique. I thought that what we were doing somebody else was doing in Liverpool and in Manchester and in every other town. But, looking back at it now, I guess we started a kind of movement, maybe.

Did you always want to get out of Sheffield?

I think most people in their teens want adventure and to run off to wherever, and I definitely always wanted to do that. I mean, I love Sheffield and I love going back there now but there was a time when it got difficult. We started getting recognised and suddenly the place that was your hometown becomes something else… we weren’t getting chased down the street like we were fucking Britney Spears or anything but, you know, we’d go out and it would get weird. That certainly helped me on my way down to London.

How do you deal with fame now?

Out here I don’t have to really. It’s very rare that someone comes up to us. Every now and then someone will but it’s always the maddest people that you wouldn’t expect. It blows my mind what the Arctic Monkeys’ demographic is – it’s a mystery. The other day an old bloke in the queue for the coffee shop said, ‘I just flew in from Indiana the other day. Are you from the Arctic Monkeys? We love your music, great to see you.’ I wasn’t expecting that… (Laughs) Then, another time, it’ll be some kids, but it’s rare here. You know, there are bigger fish to fry in this town. There are a lot of faces so it’s easy to blend in. When it happens I can deal with it a lot better now; as a belligerent 17-year-old I was a bit more like, ‘What the fuck is going on?’

What stage are the Arctic Monkeys at in their career? Does music feel like a career?

Yeah, it does in the sense that I’ve come to terms with the fact that this is what we do now. For a while there was no certainty about that; it was like, ‘Are we really just going to write songs and play rock’n’roll?’ But now I’m like, ‘Well, if that’s what we’re going to do then let’s do it well – do it right.’ (Laughs) So, yeah, we’re just at that difficult fifth record stage now… we’re writing at the moment and we’ll start recording in the spring.

Can you write anywhere?

I need a bit of solitude to be able to write because it’s like working out an equation. My notebook is full of of slashes, squiggles and arrows. But when it comes to singing the tune, I never read it off the notepad because, by that stage, I know the answer. I like Nick Cave’s approach to writing: he has an office in his house and he goes and writes there from nine to five and then quits for the day. He says that he doesn’t understand people that just write a tune on the back of a cigarette packet – and I concur with that. Usually I’ll sit there for fucking weeks – or months even – recalibrating the song. It’s like a piece of machinery that you keep on tinkering with.

How do you know when it’s finished?

Well, sometimes there is definitely a lightning bolt moment – you know, that ray of light when you think, ‘Now that’s a song!’ and it almost writes itself. But that’s rare.

While you’re writing a song, do you worry about how it’ll be received?

It’s important that it doesn’t suck – excuse the Americanism! I want to get it right and, yes, I suppose there is pressure to do that. I think that anyone who says they don’t feel that is lying. I definitely think about who is going to hear it, and I always have; it’s just that the number of people who are going to hear it has multiplied a bit. But the trick is not to let that influence you.

Are you happiest in the studio recording or on stage performing?

I would have to say the studio, but only by a hair. There is something about being in the studio because, in some ways, you never get it that good again. It’s the first time you get to know a song; it’s like your honeymoon period with that song and then, as you play it live, it becomes like that joke you tell every night.

Would you describe yourself as a control freak in the studio?

Yeah, probably… (Laughs) well, definitely. I think somebody needs to take the reins and I’m happy to do that. I’m sure it’s quite annoying for other people at times, but I think they’re glad that someone is… not exactly in charge but has a vision.

Have you ever come to blows?

No, not yet – but there’s always time! To be honest, I think we’re all past that point now: we’ve all grown up together and unless someone is really being a dickhead, we don’t fall out. It still feels just like four old friends who used to hang out on the same street rather than bandmates. Apart from if you were in the Navy or something, I guess it’s quite unusual spending that much time with four blokes… and even more unusual to not end up fighting each other.

On stage, how do you know when you are really connecting with an audience?

When you see that the bored guy who had his arms folded is now waving them around, or when that girl who has been texting all night finally looks up! (Laughs)

Have you really seen a girl texting all through a show?

Oh yeah! It was a real challenge when we first arrived in America. We were used to playing the O2 Arena with everyone singing our songs and having a bit of a party, and then we’d come here and play a small venue in Florida and some hick would be shouting, ‘Come on, man! What is this?’ But I love those sorts of shows where you have to try and convince people. You have to become ten times more animated and really rattle everyone’s cage.

During a performance, are you lost in the moment or in total control?

It’s strange sometimes because my mind just wanders off and mad memories pop into my head and I start thinking about some person, and almost forget where I am. But that’s part of the fascination; that’s why you’re up there. The audience is watching this guy on stage going somewhere else and they’re captivated by it – at least, I am when I watch groups. I mean, you’re there for the music but you’re also there for that…

Is it a transcendental experience?

I don’t know what to call it. To be honest, I’m just trying to fucking remember the words half the time.