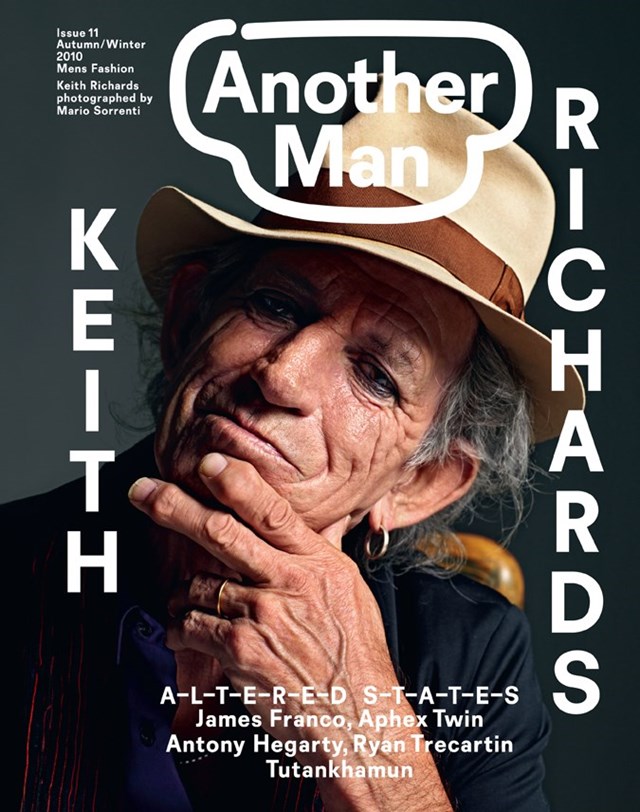

Keith Richards

Up on 76th street in Manhattan, just a block from Central Park, Keith Richards sat in a rose-painted suite in the Carlyle Hotel, where he picked at the keyboard of a grand piano. “If they don’t tune up the pianos properly,” he said sardonically, “I’m not coming back here again.”

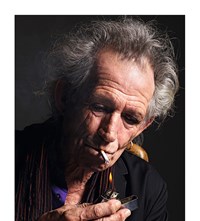

Richards swirled the ice cubes in another giant tumbler of Nuclear Waste – the potent mixture of vodka and Sunkist orange he turned to years ago when his stomach could no longer cope with the Rebel Yell – and worked his way slowly through a packet of Marlboro. The infamous jewellery – the skull ring and the handcuff bracelet – clinked and rattled. His words, occasionally tinged with the softened mid-Atlantic consonants of a boy from Dartford who now lived in Connecticut, often slurred into one another; his voice, scorched over time into a warm rasp, rose and fell with comic theatricality. He answered every question with good humour, and offered up sharp one-liners and seasoned anecdotes from his years of buccaneering junkie-dom; eventually, he pulled a huge knife from his waistband. His laugh emerged as a conspiratorial saloon bar gurgle: “Hurgh. Hurgh. Hurgh.”

This, then, was the Keith Richards I met one winter afternoon: at 64, he was no longer allowed by his family to get behind the wheel of a car, but had otherwise enjoyed the excesses and privileges of the rock star life for more than four decades: longer, perhaps, than anyone else alive. “I’ve never had to say ‘sir’ to anybody,” he told me, “since they threw me out of school.” I had come looking for the legendary Keef – blade-wielding outlaw guitarist and well-oiled storyteller, the Peter Ustinov of Quaaludes and cocaine – and he duly obliged.

And yet – after the 2006 fall from a tree that led to brain surgery, his cameo in Pirates of the Caribbean and his appearance in a Louis Vuitton campaign, it’s easy to forget that Richards has actually lived the life his persona may now seem to parody, and to have trodden a path as often beset by anguish and misfortune as that of the original bluesmen he has idolised since he was a teenager: the drowning of his friend Brian Jones less than a month after firing him from the Stones; enduring the days spent waiting for Anita Pallenberg, his then-girlfriend and future mother of three of his children, to return from the set of Performance, where she was openly conducting an affair with Mick Jagger; and the death of his second son, Tara, in his cot in Switzerland in 1976. Easy, too, to let the glamour of his 70s rebel image obscure the reality of an almost ten-year heroin addiction, which eventually proved as destructive and squalid as was possible for a man still cocooned in the luxuries of rock stardom: by 1977, Keith was at the centre of a degenerate circus of dealers and hangers-on, who once sat in the living room of his house at Redlands and watched as Anita screamed abuse at him, and his eyes quietly filled with tears.

And if the skull ring-wearing pirate mythos has almost buried the traces of the sensitive and romantic kid who, at the peak of Stones-mania in the mid-60s, according to Bill Wyman, slept with only six women in two years – and whose 1969 ballad for Anita, “You Got the Silver”, is filled with as much raw longing and vulnerability as any love song ever written – then two decades of “wrinkled rocker” clichés, corporate tours and hall-of-fame induction ceremonies have also served to dilute the significance of what Richards had achieved by the time he was 30. After the early years of chart sensation that spawned “Satisfaction” and international pop stardom fell away, it was Keith’s soul and musicianship that drove the dazzling series of albums that began with Beggar’s Banquet and ended with Exile On Main Street. At a time when the risks of being in the first wave of the counterculture were very real – “I’ve never been hated by so many people as in Nebraska in the mid-60s,” he once said. “You could just tell that they wanted to beat the shit out of you” – it was Keith who faced down the prosecuting barrister during the infamous 1967 drug trial by assuring him, “We are not old men. We are not worried about petty morals,” and was sent to Wormwood Scrubs for his trouble. Almost incidentally, while Mick ascended into the jetset, it was Keith who – with his haircut, his guitar sound and his truculent disregard for authority and his own physical well-being – established the blueprint of the modern rock star: the first and greatest, against which everyone from Mick Jones and Johnny Thunders to Pete Doherty subsequently measured themselves.

Since I met him, Richards has completed his autobiography, and there seems every chance the book may finally place his public persona in its true context. At one point during the following conversation, he told me a familiar story about staying up for nine days in a row, but then quickly added, “This was in the 70s. I’m a really straight old man now.” At the time, I thought I saw a glint of irony in his eyes as he said it. But perhaps I was wrong; it was recently reported that he had even stopped drinking. Keith Richards will be 67 in December.

ANOTHER MAN: You’re writing your autobiography at the moment… Do you have a better memory than everyone thinks?

KEITH RICHARDS: (Laughing) Yeah... I’m not spilling all the beans, it’s not dishing dirt and it’s got very little to do with money. What I’m trying to do is to write a cohesive – if it’s possible – story of what it’s like to do what I do. And it might just be volume one.

AM: Have you been keeping diaries all this time?

KR: Keeping diaries? I mean, come on, I’m Keith Richards! But I have endless amounts of notebooks that have got ideas for songs, people’s phone numbers, you know, ‘Oh my God another funeral!’ – just ideas and bits. There’s three months here in 1963, and four months there in 1970-something. And I’ve been going through a lot of that to reconnect myself. It’s quite a story.

AM: Bill Wyman claims to have slept with more than 1,000 women.

KR: I’ve never counted.

AM: What do you think your total is?

KR: You know, I’ve never gone for the bodycount. I’ve slept with... I’d say, some of the most beautiful women in the world, who I will never name, and they know who they are – but I’ve never been in for the bodycount. I’ve seen women go in and out of Bill Wyman’s room, ten minutes at a time, by the time you’ve had a cup of tea. You call that sleeping? I call that just bodycount. And if Bill feels like he’s the stud of the century, well, let him carry on thinking so. Given my reputation, I’m very, very… frugal in that area. If I’m with a lady, I’m with a lady. I just never can say goodbye, you know? I can only say hello.

AM: Charlie Watts once said the secret of a successful marriage is separate bathrooms. You’ve been married nearly 30 years – what do you think the secret is?

KR: Well, Charlie has his point of view about things… and I very rarely bathe. But Charlie’s probably right. A successful marriage? It depends on the woman, you know? It’s really friendship. I don’t care how many bathrooms or separate wardrobes you’ve got. Can you end up in bed together each night and say, ‘I know I’m a son of a bitch but, hey, here we are’?

AM: You once took a three-day road trip with John Lennon in England. So, where did you two go and what happened?

KR: Oooooh… if only John was alive, we may have a little bit more info. This was in about 1966 or 67. We went first to Torquay and then Lyme Regis, but what h a p p e n e d and why we were in these places neither John nor I could ever remember. I mean, we must have been on something exceptional. There was one young lady with us at least, and a chauffeur – I know we were in no driving condition – and we were just playing sounds. We were in my Bentley, because I said, ‘I’m not going on a trip with you in that goddamn psychedelic Rolls Royce. Let’s go more discreetly in my little blue Bentley.’ We just drove, played music and had a laugh. John was a barrel of fun, actually.

AM: In retrospect, the sound of ‘Gimme Shelter’ has become shorthand for the end of the 60s. Do you remember where you were when you wrote it – and how you felt at the time?

KR: Yeah – I was in Robert Fraser’s apartment, 21 Mount Street, Mayfair. Mick and Anita and Donald Cammell were away shooting… whatever it was called.

AM: Performance.

KR: Performance – yeah and it was a fuckin’ performance… Anyway – so, having a bit of spare time on my hands, so to speak… and at the same time there was a nasty thunderstorm coming in over London, and I just started to hammer it away.

AM: When you wrote the opening, how were you feeling? It’s very apocalyptic.

KR: It’s difficult to say – you put your hands on an instrument, and – I mean, I really don’t like to think about it. I like to look at my fingers and say, ‘I don’t believe you’re doing this – keep going!’ You don’t create things, you accept them. And all you want is for that feeling to continue – your mind is disconnected from what you’re doing.

AM: Is it true you once fell asleep on stage in the middle of playing ‘Fool To Cry’?

KR: Yeah – that’s definitely true. It’s a very boring song. Mind you – I was pretty out of it. But yeah, I was on one of those (volume) pedals, and I just stayed on it – Hmmmm! It got so loud that I had to wake up.

AM: At the nadir of your heroin addiction in the early 70s, you apparently took up skiing...

KR: Yeah – you try living in Switzerland for two bloody winters. The first winter you almost go bananas, because it’s gloom, sheer gloom. And suddenly you’re there for a second winter and somebody says, ‘Hey, up there there’s bright sunshine and loads of things happening and all you’ve got to do is put these silly things on your feet and zoom down a hill.’ Okay. I’d rather be up there with the sunshine than another winter of gloom.

AM: Were you good at it?

KR: I eventually got very good at it, but the most embarrassing thing about skiing is that you start on nursery slopes, and they’re not called nursery for nothing; all you’re doing is falling over, and little four-year-olds are going by you going, ‘Haha hahahahaha!’ But in two weeks – baby! I’m rockin’ down the moguls and ending up at the bar and having a great snifter and going back up. But Switzerland to me was a prison – and that was the way I could get out.

AM: What’s the worst prison cell you’ve ever been in?

KR: I can give you the run-down of several tanks. The worst was Wormwood Scrubs, I’d say. You kind of felt all the other guys that must have been in there, for a hundred-odd years. I was only in there 24 hours, but it was the longest 24 hours I can remember. You get this goddamn shabby uniform, walk round in a circle and see the 60-foot high granite wall. The cell was probably no worse than a lot of Holiday Inns I’ve been in – it was just the fact that you couldn’t get out. That was the tough bit.

AM: What exactly is a ratchet knife and do you still carry one?

KR: (Keith lifts his shirt, reaches into the waistband of his trousers and produces an enormous bone-handled folding knife, and swiftly snaps a four-inch blade open and closed) That’s a ratchet knife – now you see it, now you don’t! (Flicks blade open again with a sudden twist of his wrist) It’s just like that, you know? And the actual cut is across here (traces a horizontal line across my forehead with his finger) – doesn’t hurt! All the blood comes down, and then you kick the fucker in the balls. It’s a very efficient way of dealing with problems. I learned it in Jamaica, and I’ve always carried one. And I gave up the shooter. Look at the horn, it’s beautiful work. I mean, look at this...

AM: Where did you get it from?

KR: I’m not going to tell you! Hurghurghhurgh!

AM: What was the first gun you bought for yourself?

KR: I believe it was a Luger that I picked up in the East Village in New York City in 1965. After that, I went into rifles for a bit – just because, uh, they go further… (laughs). I’ve only carried a piece or two now and again, and most of that was to do with the heroin business and being involved in, like, scoring. And especially in America, it bodes you well to be armed. You don’t expect to use it. A .38 Smith and Wesson Airweight revolver. That is the fucking gun: no safety on it.

AM: I’ve seen a YouTube clip of you hitting a fan with your guitar when he invaded the stage at a 1981 Stones show in Virginia – what was going through your mind?

KR: It was really just a normal reaction. There’s a guy rushing to get hold of Mick, who’s my mate, right? Since there’s no security available, I’ve got to take care of my mate – and the only weapon at hand is my trusty Telecaster. I just took it off – it was in the middle of ‘Satisfaction’, I remember that – and I thought, ‘Here goes the tuning!’ And I whacked him right behind the neck, and put him over Charlie’s drum kit; I got a terrible look from Charlie. I knew he was down, and I put the guitar on, and the damned thing is not out of tune at all.

AM: What happened to the guy afterwards?

KR: He got arrested... and I bailed him out. Hey – he was just out of it, you know.

AM: Who has the meanest punch of anyone in the band?

KR: Charlie Watts. I’ve seen him deck guys twice his size. He’s a drummer, innee? You know, look at the man’s job – he has wrists like that. Never get in the way of a drummer, man.

AM: In 1998, you fell off a ladder in your library reaching for a book. What was it?

KR: Oh, this is one of those terrible things that people always call me a liar for, but it’s true. It was Leonardo Da Vinci’s book on anatomy. Ha! And it hit me, knocked me off the ladder, and I found out all about anatomy from that without even opening a page. But it’s like, ‘Well, yeah, that’s one of Keith’s stories, blahblahblah.’ But it happens to be true.

AM: You broke three ribs, right?

KR: Yeah, yeah, yeah. And punctured a lung. Yeah.

AM: What’s the secret to a great shepherd’s pie?

KR: Ah! Now, this is a good one. Whether you use lamb or beef, it doesn’t matter. My mate, who’s now the long-lost, great (former Stones security guard) Big Joe Seabrook, taught me the one final trick is to put in some extra sliced fresh onion just before you put it in the oven.And I find that works – and shove it up your arse, Mrs Beeton!

AM: And do you make it yourself?

KR: Yeeeeah! You gotta do it yourself!

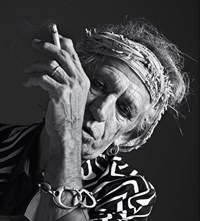

AM: How do you choose the things you tie in your hair?

KR: I’ve got loads of boxes of crap that people send me. The ones that remain are the ones that have stayed tied in. Sometimes my daughters and my wife snip me off while I’m asleep – I have to look to see that I’ve not been circumcised in the night – and others just fall out. So, I just let them rotate naturally. They just keep me balanced: I’ve always felt slightly lopsided.

AM: Was there ever a point where you thought you’d never play with the Stones again?

KR: Nah… never. I suspected in the late 80s that there was gonna be a hiatus when Mick called the Stones ‘a millstone around my neck’. I knew there was a possibility we would not get back together, but I thought, ‘Shit – we’ve been together for so long that maybe we need this break.’ Everybody had to spread their wings. Mick did his best and flapped about like a chicken, and I did the X-Pensive Winos and really flew like an eagle. After that everything came back together again.

AM: Of all the Stones, whose solo work do you think is best?

KR: Charlie Watts. Mick’s stuff disconnects when he goes off by himself, Ronnie’s done some good stuff here and there, but I’d say that Charlie has done some excellent stuff – especially with his jazz orchestra. Otherwise I’d say me. With the X-Pensive Winos, who’ve got to be one of the best rock’n’roll bands I’ve ever worked with.

AM: You used to call him Brenda, you’ve suggested he brown-nosed to get a knighthood and that he has a small penis. Do you enjoy winding Mick up?

KR: Oh yeah – he deserves it. Who else could do it? Nobody else has the fuckin’ bollocks!

AM: What’s the most ridiculous thing you’ve ever spent money on?

KR: Spending money is a weird thing. I’ve spent my life just working and doing what I want to do – and realised slowly that I’m making loads of money. But that’s not why I’m doing it. You just accumulate this amazing wealth. I’ve probably got far too many guitars. I have 3,000, and I’ve only got two hands.

AM: When was the last time you went two days without sleeping?

KR: Um... Last Friday... Friday through Sunday last week. I got home and I hadn’t seen my old lady for a while, and spent all night makin’ up time, you know? And the next day I couldn’t sleep anyway. Two’s nothing for me. I think nine days is the longest that I really did. But it wasn’t a matter of trying to stay up. I’ve got a lot of energy – I mean, sure, I had a little help. I used to like pure, pure cocaine – which is a very smooth thing – it’s got nothing to do with the street shit other people take. I was very Peruvian about it – it was like chewing the leaf. I never took anything without researching what it was. I’ve got to admit that sometimes I probably overdid it, but that was the nature of my game at the time. I don’t feel proud about staying up for nine days. I certainly don’t recommend it – for anyone.

AM: Do you think musicians like Amy Winehouse and Pete Doherty take drugs for different reasons to the ones you did when you were their age?

KR: It’s the same old thing – all I’d say is you should take your drugs in your spare time, if that’s what you want to do, but don’t mix it up. If you’ve got something to say and something to do, then do it. And if you wanna take dope, do it when you’ve done what it is you want to. If you mix it up together, you’re just gonna fall like a million others. I’ve seen too many friends gone that way. I’ve had a word with Pete about this, but it don’t make any difference. I think he’s a squealer – I think he has ulterior motives.

AM: Have you ever been in danger of believing in your own public image?

KR: The only danger is trying to get away from it, and it catching me up. You don’t have much to do with forging a public image. It’s forged for you by the media, and by time. And you suddenly realise that you’ve got one. I always wanted to be a chameleon; now it’s all skulls and pirates. The image becomes a bit of a ball and chain – you get stuck with it, but then you realise that maybe that’s who you are, and it’s not such a put-on as you sometimes feel… (but) I mean, I’ve got kids, and they think I’m a pirate. And I’m really not one, you know what I mean?

AM: You’re often characterised as being afraid of nothing and no one. When was the last time that you met someone who genuinely frightened you?

KR: Fear is a funny thing: it’s only when you have to face it that you have any concept of what it means. When I looked up at Dr Andrew Law and told him to cut my head open – that scared me to death. I couldn’t believe I’d said it. I’m lying there in New Zealand and he says, ‘You’re stabilised, you can now go to New York or London, whatever – and have the operation.’ I said, ‘I ain’t going nowhere – you’re doing it. And you’re doing it as soon as you can.’ That was probably the most frightening moment I’ve had. It’s easy making decisions for other people, but when you’re inviting a guy to open your head…

AM: What’s the best part of getting old?

KR: Realising that there’s no difference between being a young guy, being a baby – you’re still learning the game. I don’t feel any different now than I did when I was 20. I mean, I realise that there are certain limitations, that I know a lot more, but – hey, the next day is still just the next day. It don’t matter how old you are. I saw my mum off at 93: I’m looking at her in the hospital bed and she’s saying, ‘Why meeeee?’ I mean, you are 90-fuckin’-three you old cow! ‘I know,’ I said, ‘I’ll play you a song.’ And I brought a guitar along and played her ‘Malaguena’, a song her father had taught me, and she said, ‘Bit out of tune, Keith.’ And then she croaked.

AM: Can you clear up the whole thing about snorting your dad’s ashes once and for all – I’ve seen you quoted as saying first that you did, then that you didn’t and then most recently that you did after all. Which is it?

KR: Well, it’s about halfway in between both of ’em. Actually... (Long pause) Do you want to hear the latest story?

AM: Yes.

KR: Alright, alright. I opened my dad’s ashes, and some of them blew out over the table, just because of the suction of the lid, you know what I mean? And, I mean, I no longer do cocaine – I’m not allowed to since I broke my head open. Otherwise I’d be right in, baby! Nothing stops the old snorter. But I can’t do it, I don’t do it. But I looked at my dad’s ashes down there and – what do I do? Do I desecrate them with a dustbin and broom? I mean, what am I gonna do? So what I did, I wet me finger and I went like that (licks finger) and I shoved a little bit of dad up me fuckin’ ’ooter. And, I mean, I’m sure he’s still blessin’ me. The rest I put round an oak tree – which is coming up a treat.

AM: What do you think happens when you die? Is there anything on the other side?

KR: Now that’s going into realms beyond my capabilities. Let me put it this way: I’ve thought I’ve been dead several times. And there have been times where I’ve just left the body and watched things happen. I watched a three-tonne car turn over and I’m driving, but I’m watching the car turn over three times – and it’s a convertible… (Laughing)… and it’s rolling and rolling. But I’m watching it all from above. Now what happened was that the car came straight down – bang! – rubber side down, steaming away – and suddenly I’m back behind the wheel. That’s as far as I can go: I can say you can leave your body when you think you’re dying. But the light at the end of the tunnel might just be called New Jersey.