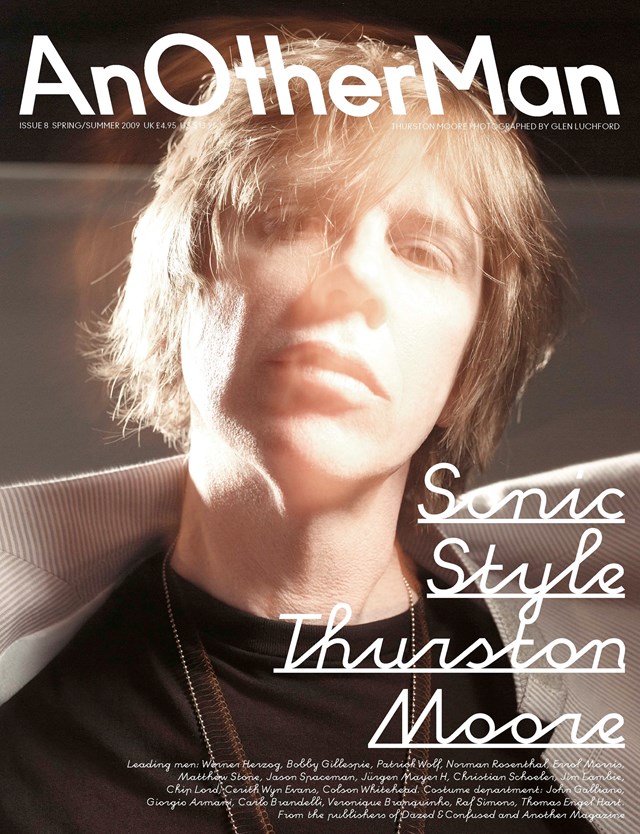

Thurston Moore

I am walking in the woods with Thurston Moore and his dog, Merzbow, a black, shaggy creature named after its owner’s favourite Japanese noise artist. Thurston is giving me the low-down on his ‘hood, this quiet, leafy corner of Northampton, Massachusetts, where he, his wife Kim Gordon and their daughter Coco have lived for the last seven years.

“Right over there is Smith College where Sylvia Plath studied and taught,” he says, pointing across a dark, muddy river that meanders through the rolling, wooded hills. “Northampton is a college town, literary, progressive, granola-liberal. There’s a big academic community and a women’s community. I guess we kind of fit in.” Well, kind of.

Although it is only three hours’ drive from downtown New York, where Sonic Youth’s unruly art-rock aesthetic was forged, Northampton is a whole world away. Around here, the postman leaves your mail on the doorstep if you’re out when he calls. I can’t see that happening on the Bowery, however gentrified it becomes. I ask Thurston if he misses the energy and edginess of the Lower East Side.

“Well, it’s close enough to be available when I need it,” he says, “but right now we’ve reached a stage where making a record is dictated by our family schedules – our daughter’s schooling, stuff like that. I mean, there are moments when I could maybe go see an amazing black metal band from Norway playing in New York, and it might be the only time I’ll see them, but my daughter has her homework to do. So I bite the bullet and help with the homework. And,” he adds, laughing, “try not to whinge about it.”

It’s easy to forget that Thurston Moore is 50 years old. In many ways, he still looks and sounds like the same lanky, floppy-fringed fan who saw the Ramones in CBGB’s in 1976 and never looked back. He exudes an air of eternal slacker cool and an unabated enthusiasm for all things extreme and noisy. Kim and he remain the hippest couple on the alt rock block, a nexus for several kinds of contemporary cultural cool: underground pop, contemporary art and photography, fashion (they recently played at a Marc Jacobs catwalk show), film, and, it often seems, every extreme variation on those same forms. They may have fled to one of the most laid-back enclaves of liberal America but they remain a busy – and culturally alert – couple.

In the last couple of years, Thurston has released his second solo album, the excellent Trees Outside the Academy on his Ecstatic Peace! label, as well as two more instalments of Sonic Youth’s self-released series of experimental albums. He has also co-authored a book on the American post-punk scene (No Wave: Post Punk. Underground. New York. 1976-1980). With Kim, he helped curate an intriguing art show, Sensational Fix, currently touring European galleries. It features the group’s various collaborations with visual artists, filmmakers and designers, from Vito Acconci to Patti Smith and John Cage to Gus Van Sant. Kim’s other group, Free Kitten, also released an album, and she started a clothing line called Mirror/Dash whose first creation is a limited edition “military-style wool jacket inspired by Françoise Hardy”. For such a laid-back couple, they manage to fit a lot in.

“I guess so,” Thurston says, nodding, “But it’s good busy. It’s like, people always say, ‘Why do you put out so many records? Why do you do so many gigs?’ Well, I’m in the music business. Personally and professionally. I don’t understand why more people don’t do the same.”

Sonic Youth are now 28 years old and have somehow managed to retain what could be called their arty primitivism against all the odds. They were formed in 1981 just as New York’s no wave scene was fragmenting, and the key to understanding their uniqueness lies, I think, in their roots in the downtown art scene. Both Kim and guitarist Lee Ranaldo were artists before they became musicians, and the group’s first gig in New York was in a gallery rather than a bar.

“We played Jenny Holzer’s loft and that’s the scene we hung out in,” explains Thurston. “Initially, the downtown art world was our audience. When I first met Kim, she was doing performance pieces using electric guitar. For a long time Sonic Youth were about the performance thing rather than the straight rock thing. We were, and to a degree still are, very art world. Our cover artwork has always denoted that.”

Sonic Youth’s album covers provide the most consistently illuminating signifier of their otherness. Daydream Nation featured a Gerhard Richter painting, Dirty was designed by Kim’s long-time friend the American artist Mike Kelley, and Goo came clothed in a Raymond Pettibon illustration. They have worked with the conceptual art photographer Jeff Wall, and the porno-art pioneer Richard Kern. “With us, it has always been about this whole community of like-minded activity,” says Thurston, “Whether it’s the artists we use, or the groups I sign to Ecstatic Peace! It’s not self-centred. If you want to talk about a governing aesthetic, that’s it right there.”

Right now, Sonic Youth are undergoing another bout of reinvention. Think Sister from 1987, where they started writing real songs, or Daydream Nation from the following year, where they reclaimed the double album as an artistic statement. Think Goo (1992) and Dirty (1994), when they held out against the post-grunge tide of Nirvana copyists and flew the flag for intelligent, noisy rock. This time round, though, change has been, to a degree, imposed on them. The force of nature that is musician-cum-composer Jim O’Rourke left the band, and has been replaced, for the time being at least, by Mark Ibold, late of the second most influential American art-rock group of recent times, Pavement.

Last year, too, they finally parted company with Geffen Records, the major label that always seemed an unlikely home for a band who, in all senses of the word, are resolutely independent. “We were like a boutique group for them,” says Thurston, who seems genuinely relieved to be free and independent again. “We were always seen as the group who brought Nirvana to the label, and I heard later that no one wanted to be the person that fired Sonic Youth. Which was disappointing because we were like, ‘Please let us go.’ At one point, we were going to call the last album You Can’t Sell This.”

Their new album, The Eternal, is their 16th, and their first for their new record label, Matador, a mid-sized independent that seems more suited to their often wilfully perverse aesthetic. It is named after, of all things, a Joy Division song. “That post-punk era of songwriting has become a source of inspiration to us in some way for this record,” explains Thurston. “We have been giving the songs working titles like ‘The Fall’ and ‘MARS’ [a late 70s New York no wave band]. One song does sound very Joy Division, though they are the last group I would claim as an influence.”

How would he describe the album? “Well, there are no eight-minute-plus pieces; they tend to be three-minute celebratory songs. It’s basically a bunch of fun, happening Sonic Youth songs.” Maybe, I suggest, they are finally mellowing out. “Maybe,” he nods, looking slightly uneasy. “When our daughter was born, I think it created a new vibe for Kim and me. And maybe that affected how we composed music lyrically. It had a deep spiritual effect on us but it’s not something I could articulate.”

The presence of the pram in the hall, though, has done little to puncture Thurston’s work rate. When we meet, he is in the middle of playing a brace of noise gigs on the East Coast, just him and his guitar and whatever local experimental musicians are available. “It’s usually a bar or a basement with 20 people in the audience, half of whom are disappointed Sonic Youth fans,” he says, only half-jokingly. His dedication to freeform experimental music is total. Likewise his commitment to what he endearingly calls “the underground”. When I ask him if he really thinks such a concept exists anymore, and, if so, where Sonic Youth fit into it, he understandably takes his time before answering.

“There’s certainly a big underground in what you might call extreme outsider music and the shared knowledge is incredible,” he says, sounding genuinely excited. “That’s the real success of the underground. It’s like there is no mainstream any more except the super-mainstream of Disneyfied pop music.”

Last year, though, as if in perverse celebration of their freedom from Geffen, Sonic Youth embraced the super-mainstream by releasing an album via Starbucks. It was called, with a certain self-mocking irony, Hits Are for Squares. The tracks were chosen by other artists-cum-fans from the hipper end of the pop cultural spectrum: Beck (“Sugar Kane”), Dave Eggers (“Tuff Gnarl”), Gus Van Sant (“Tom Violence”), Catherine Keener (“Bull in the Heather”) and Chloe Sevigny (“World Looks Red”). Even more ironically, it may yet turn out to be their all-time biggest seller. It often seems like they make up the rules as they go along.

“We consider ourselves a living band,” says Thurston. “We’re hardly calculated. We’ve generally always done what we do in the moment and on the seat of our pants. It’s all very loose.” Starbucks aside, have their records ever made them any real money? “Not really. It’s like, we don’t cost much money and our records tend to break even. We don’t have people around us insisting on our super-functionality. I guess we never made the kind of money that brings that kind of pressure.”

Before I depart for New York, Thurston Moore shows me around the basement of his big house. It’s a trip in itself. One section has been turned into a rehearsal space, and is littered with cables and instruments and amps. The other members of the group – Lee Ranaldo, Steve Shelley, Mark Ibold – come up to Northampton for a couple of days’ rehearsal every week. “We write a couple of songs, then go up to NY at the weekend and record them,” says Thurston. “It’s a new way of working for us and one that doesn’t allow for a lot of development. It’s more instant. It has,” he adds mysteriously, “been a challenge to some.”

The basement also contains Thurston’s record collection, wall after wall stacked high with rare and obscure records. It’s easily the biggest archive I have seen since I visited the late John Peel’s house back in the 1980s. The section devoted to Norwegian black metal is bigger than my entire record collection. He pulls out an album at random. The sleeve features a naked nubile covered in blood. “That’s a kind of generic death metal cover,” he deadpans. “She’s probably the drummer’s girlfriend.”

Another basement room houses his collection of cassette mix tapes, personalised compilations that friends and strangers have sent him from across the globe. “When you look at the detail that’s gone into not just the selection of music but the cover illustrations, it’s almost like outsider art,” he says. “These are valuable documents. I think they should be preserved for posterity as a glimpse of popular culture in a time of fragmentation.” To this end, he has also edited a fascinating book, Mix Tape: The Art of Cassette Culture, which celebrates these DIY labours of love.

Thurston can talk for hours about his enthusiasms – punk, post-punk, hardcore punk, no wave, glam rock, black metal, death metal, Japanese noise rock, the European free jazz tradition and America’s fragmented but burgeoning weird folk scene. Were he not a rock star, you could imagine him lecturing on The History of Improvised Noise at a progressive American college. I ask him how long he intends keeping going. He seems surprised by the question.

“I really feel there’s a new liberation about what we’re doing,” he says. “The new songs are different. It’s as if we can write Sonic Youth songs without even having to think what the aesthetic is any more. My favourite bands back when we started were Public Image Ltd and the Runaways. That’s where we’ve always been at as a group. We’ve always aimed for that elusive hybrid of radical experimentalism and straight up rock and roll. We’re not a typical rock band,” he says, laughing, “but we’re not a typical underground experimental band either. I think that’s what attracts our fans and confuses everyone else.”