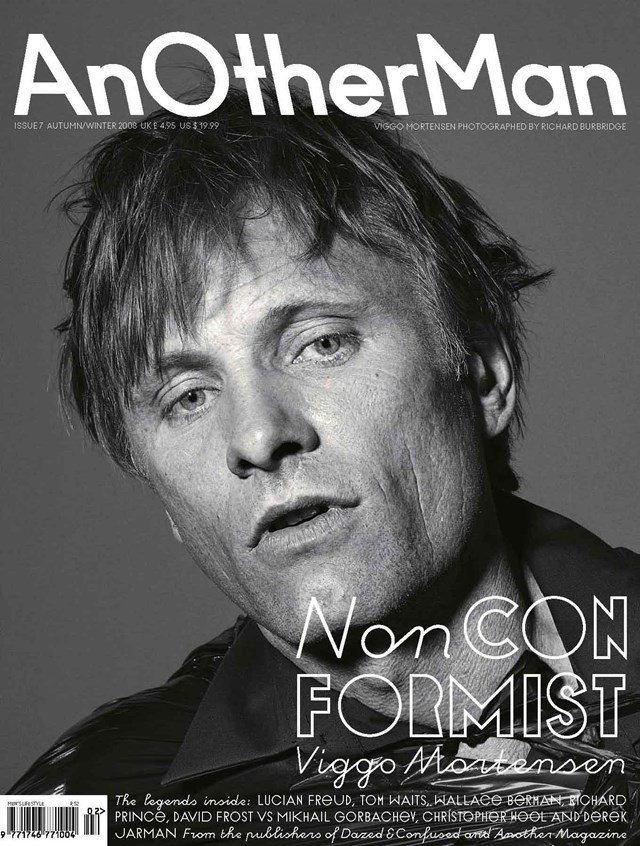

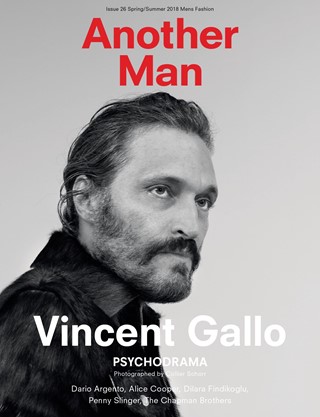

Viggo Mortensen

“When it was light enough to use the binoculars he glassed the valley below. Everything paling away into the murk. The soft ash blowing in loose swirls over the blacktop. He studied what he could see. The segments of road down there among the dead trees. Looking for anything of colour. Any movement. Any trace of standing smoke. He lowered the glasses and pulled down the cotton mask from his face and wiped his nose on the back of his wrist and then glassed the country again. Then he just sat there holding the binoculars and watching the ashen daylight congeal over the land. He knew only that the child was his warrant. He said: If he is not the word of God God never spoke.”

The Road, Cormac McCarthy

Viggo Mortensen pulls no punches, whether he’s playing a Russian mobster rolling naked around a sauna with a knife up against his groin in Eastern Promises, or just sitting back and talking about making movies and the state of politics in America. Just listen to what this uncompromising, 50-year-old actor with three decades of experience has to say about working with film directors: “I’m not going to assume that anybody’s going to help me to construct a character,” he says, his laid-back drawl sometimes dipping to a barely audible murmur as our conversation wanders towards the two-hour mark.

He’s been talking down the phone from his retreat on the Canadian border about the movies he’s made, the awards he’s never won, the politicians he admires and detests, the approaching American election, and how he hopes soon to see George Bush and Dick Cheney on trial for war crimes. “Historically, if we don’t prosecute them,” he says with characteristic frankness, “it will always be a black mark against our country.” Right now, though, he’s explaining how his approach to acting is to trust nobody and to be as self-sufficient as possible. It’s this same attitude that explains those stories that crept out last year about how he wandered off alone while on an exploratory trip to Russia, both to learn the language and to discover more about the criminal underworld, all in preparation for playing a mafia man in David Cronenberg’s London-set gangster thriller, Eastern Promises – the same film that famously had him baring his entire body for one of the most thrilling fight scenes committed to film. It’s a mark of Mortensen’s drive for authenticity that there was nothing between his bare flesh and the camera but thin air.

All this may sound a little brash, but as the conversation goes on Mortensen’s attitude doesn’t sound anything like arrogance or paranoia. He isn’t earnest. Rather, it sounds like this actor, whose career blossomed relatively late, when he was in his early 40s and already had a respectable roll-call of smaller and supporting roles behind him, from Sean Penn’s The Indian Runner to Gus Van Sant’s Psycho, has learnt over the years not to expect anyone to hold his hand. His mantra is to trust nobody. “I’ve learned that most of the time you don’t get much help from a director,” he says. “You’re on your own and so I definitely try to show up on set with as much information as I can, whether it’s language or accent or birthplace or history. I always do that work on my own. Most directors are jerks. They may be talented. But they may also not be very good at or interested in talking to people. Too often, when making films, energy is expended on quibbling and miscommunication rather than productively telling the story.” He pauses. “Of course, some of us actors can sometimes be jerks too.”

All of which explains why he loves working with Cronenberg. He’s got a huge amount of admiration for the man, not only for the end product of his filmmaking, but also for the way he handles people, the way he’s able to explain his ideas and to make everyone feel involved. That’s what Mortensen likes: good, down-to-earth, everyday communication. He’s not someone who believes art should carry with it struggle and misery. “David Cronenberg is such a respectful director; he’s by far the best communicator I’ve ever experienced of the directors I’ve worked with. A lot of directors, even the smart ones, who are very conceptual, just don’t communicate well, whether it’s because they’re insecure or far too self-involved, they don’t relate well. But David Cronenberg and also someone like Peter Weir are just so calm. It’s fun to go to work. You want to give them your best effort.”

Just as he can’t be doing with high-minded aloofness, neither does Mortensen do jolly. Just think of those films he made with Cronenberg, the Canadian master of fear and precision. The first, A History of Violence was about an average suburban guy who lives a secret life as an assassin and has to defend his family from murderous criminals when his cover is blown. In the second, Eastern Promises, Mortensen plays a hard-faced, fearless driver to a Russian mafia family living in London. Even in The Lord of the Rings films (those three megalithic fantasy movies that turned him from a supporting actor into a household name) he was never called on to crack a smile. While others in the cast played at elves, wizards and mysticism, Mortensen rode on a stately horse as Aragon, whose most expressive tools were his sword and those striking Nordic looks that hinted at Mortensen’s Danish ancestry – his father is Danish, his mother is American and he was raised in New York, Venezuela and Argentina (he still speaks fluent Spanish among a number of other languages and was nominated for a Goya, Spain’s version of the Oscars, for the lead role in Spanish film, Alatriste, a box-office smash in Spain last year).

However, it was Eastern Promises that brought Mortensen his first bout of major awards nominations earlier this year, including a nod in the best actor category at the Oscars, the Golden Globes and the Screen Actors Guild Awards. He looks back at that period now, those strange few months of walking up red carpets and watching presenters opening envelopes containing Daniel Day-Lewis’s name, “as a very strange thing to watch, but it was interesting too. I was part of that travelling thing, that awards circuit.” Did it feel like a lot of commitment for little return? “Yeah, but it depends how much you make of it. I mean, most of those guys, they did the whole thing, they went to every event, and I didn’t do that. I mean, I was working, so I did my job as I always do to promote the movies, but as far as trying to get myself a prize, I didn’t do that. I’m surprised I even got the nominations. I felt like something of a tourist really on the circuit, just taking it all in. I looked at the whole thing really as an acknowledgement of Cronenberg more than anything else.”

Now that autumn and the new season of serious films is again on the way, Mortensen is beginning to feel the vibrations of the same machine as it warms up once again. He spent the past year and a half working hard on three movies. “Three completely different stories, three completely different characters,” he says. A few days before we speak, he was in Portland, Oregon shooting extra scenes for The Road, the second film after the outback western The Proposition from Australian director John Hillcoat. It’s an adaptation of a novel by Cormac McCarthy, and after the success of last year’s No Country For Old Men, another McCarthy tale, there’s already a buzz about awards before anyone’s even seen it. Before The Road, Mortensen spent a couple of months in Hungary making Good, a serious drama about political culpability in 1930s Berlin, in which he plays an academic who gradually gives himself over to the Nazi cause in order to maintain a quiet life. First off the blocks, though, for this latest bout of intense work for Mortensen was Appaloosa, a traditional sort of American western that was written and directed by the actor Ed Harris. Mortensen plays a hard-nosed law enforcement officer trying to police a renegade town at the end of the 19th century and stars opposite Harris himself.

Both The Road and Good are Mortensen’s kind of films: bleak tales of men struggling against their environment, battling against overwhelming outside influences that threaten to swallow them whole. Today both spark thoughtful, engaged paths of conversation from Mortensen. McCarthy’s novel is a masterpiece of description that tells of a man and his young son on a journey through an apocalyptic, mysterious landscape in which fires burn, buildings are destroyed and there’s danger at every turn. Nothing’s clear apart from the reality that everything’s changed and nothing’s certain. Mortensen and his colleagues, including youngster Kodi Smit-McPhee and Charlize Theron, shot most of the film on location. They went to Pennsylvania to soak up a backdrop of old steel factories and where “it is kind of polluted and bleak-looking, especially in the winter”. They went to New Orleans and filmed at some abandoned shopping malls that hadn’t been touched since Hurricane Katrina, and, perhaps most spookily of all, they travelled to the site of Mount St Helens near Portland, the volcano that erupted catastrophically in 1980 and where the trees still all lie strewn in one direction after the devastating blast that killed 57 people.

Mortensen tells me that he spoke to Cormac McCarthy on the phone before they started filming and the 75-year-old novelist offered to speak to him as often as need be. As it turned out, the pair had only one conversation and that was mainly about their respective kids. When they’d almost finished shooting the film, McCarthy came down to the set in Oregon and, Mortensen remembers, seemed pleased that the director was following his vision closely. “Another director with a bigger budget would have made much more of a special effects movie out of it, and I think that would have taken something away from it,” Mortensen explains of how he thinks The Road, which is still in the edit room when we speak, will turn out. “At least in my opinion, if the movie works it’s going to be because of how lean it is, how gritty it is, not because they’ve laid a whole load of effects on it, like a Spielberg or a Peter Jackson would do. I think he’s tried to minimise by thinking out the design and the look.”

It’s the mystery of The Road that makes it most striking to Mortensen. “Like in the book, it could be 10 years from now, or it could be 20,” he elaborates. “It’s obviously some place in North America from what it looks like, from what’s left of it. But you don’t know whether the destruction is the result of nuclear waste or a nuclear war or environmental damage or an earthquake or a climate disaster or a combination of all those things.” The book itself is a revelation. It’s an austere, lean story that offers wonderful, poetic descriptions of a world gone wrong. The emphasis is on the relationship between this wandering father and son. They’ve both lost the woman in their life – the father, his wife; the son, his mother – and they’re travelling aimlessly, trying desperately to survive while the father attempts to keep his son safe and maintain some sense in him of what’s right and wrong in a world gone beyond mad.

“Basically, it’s a love story between a parent and child,” Mortensen goes on. “That’s what drew me to it anyway, being a parent.” He has a 20-year-old son, Henry, from his 11-year marriage to singer and actress Exene Cervenka, who he met on the set of a TV show when he was just starting out acting in the late 1980s. “It’s an extreme version of what every halfway decent parent goes through, worrying about their children’s well-being, that they will grow up to be adults and take care of themselves, so you can leave the world knowing your kids are going to be safe. It’s more extreme here, but it’s the same worry. If I go, this kid is completely alone. It’s every parent’s nightmare.”

We talk about Good, the other film he’s got coming up, and the conversation soon locks on to politics, a subject close to Mortensen’s heart in this year of an American presidential election. Back in January, he lent early support to Dennis Kucinich, the Democratic congressman and presidential candidate by flying to New Hampshire to speak out in Kucinich’s favour. Kucinich was out of the running by the end of January and now Mortensen is willing to speak out in favour of Obama, even if he has reservations. “I hope the movement that Obama created, as happened with Robert Kennedy, will prod him to go a little further in some areas than he would have, particularly in Iraq,” suggests Mortensen. “Robert Kennedy wasn’t particularly opposed to the Vietnam war, but he changed his position as a result of the pressure from the ranks of his supporters. I’m hoping that’s what will happen.”

Mortensen’s political commitment, shown by his active support of Dennis Kucinich early in the presidential campaign, is not new. He’s campaigned before, both for issues relating to our exploitation of the natural world, such as the preservation of wild horses (especially around the time of Hidalgo in 2004, when he played a 19th-century horseman), and for the rights of native Americans, a cause he speaks up for in an upcoming documentary, Spirit Riders, to which he’s lent his name and his voice. This same commitment beyond the world of the movie set can also be seen in his curatorial work with artists, photographers and writers. Mortensen runs a small publishing house, Perceval Press, through which he publishes his own photography and poems, as well as the work of other artists whose work he wants to support and distribute. “We don’t focus on one particular thing,” he says of the publishing venture, which he works on intermittently between films and when individual projects spark his interest. “I suppose we’re mostly known for publishing photographic and art books. I try to do things that are harder to find, or that people don’t know about, or that interest me, whether it be art history in Cuba or a New Zealand artist or an Icelandic artist or a book about the Russian situation. We’re going to put out an anthology of new Argentine poets soon, for example. A mixture of things. I don’t have any set goal with the publishing, any more than I do with my movies, I like to try different things and learn about things. That was the case with the three movies I worked on this last year.”

Talking to him, one thing’s for sure: Mortensen can’t wait to see the back of the incumbent president. It’s on the subject of George Bush that Mortensen is able to make biting parallels with Good, in which he plays a German academic. His character, John Halder, is not especially political, but the Nazi Party spot something in this literature professor’s only novel that relates to the debate over euthanasia. They invite him to be an honorary member of the SS and he accepts, hesitantly, but only slightly so. It’s a slow process yet Halder goes from curious observer to operating at the heart of the Nazi machine. Mortensen’s not afraid to make parallels with American politics over the last eight years.

“It’s happening now, it’s happened before,” Mortensen says of the portrayal of the slow-burn loss of liberties in Good. He’s thinking of the curtailment of civil rights in America since 9/11, of the Patriot Act, of the “with us or against us” rhetoric of the Bush government. And he doesn’t mince his words. “Look at this country I’m in right now and the administration, and what’s happened in the last eight years to the judicial system, the laws, the standing of this country in the world, education, healthcare, the economy... There have been incredible changes, and if somebody said to you would you be willing to put up with all these things and have all these laws changed, you’d say: well, no. But, by having it happen little by little, it’s like a death by a thousand cuts. Before you know it, you’re bleeding to death.”

Mortensen goes quiet for a while. He’s been sitting outside for the past hour and a bit, leaning back in a chair and talking away under the morning sun. “There’s a hummingbird right in front of my face,” he whispers gently. Mortensen is very much an outdoors man. You can see it in his photography and in his paintings, in those very personal, expressive works that he makes when away from the glare of Hollywood, and that explore the details of nature and of landscapes and play with movements of light and abstract moods. Maybe it’s his childhood playing out in his work: he grew up on various farms in Argentina and Venezuela, where his father was a ranch manager. Nature is in his blood. Maybe, too, it explains why so often he’s attracted to movies like Hidalgo and The Lord of the Rings and Appaloosa – films that take him outdoors or call for him to get up on horseback and ride out into the wild.

He’s a lone rider in the film industry, too, dismissive of its vanities and determined to make his voice heard without any fear of interfering. “Any movie that anybody makes in the end is only as good as the compromise everybody makes. It works when everybody’s willing to put their ego to one side and roll their sleeves up.” Does he think that finding himself at the top of the tree relatively late, gaining lead roles only in his 40s, helped to form this independent attitude? “Yes, a lot probably,” he says. “It helped me to learn how to do my job. I learned to be self-sufficient. Whatever class you’re in or school you go to, there’s nothing that compares to just doing it and making mistakes.”