As Mushrooms: The Art, Design and Future of Fungi continues at Somerset House, James Greig looks at our collective fascination with fungi

- TextJames Greig

Whether you love or hate them, the fascination which mushrooms have exerted over humans since the dawn of civilisation is undeniable. At the beginning of Mushrooms: The Art, Design and Future of Fungi – a recently opened exhibition at Somerset House – an introductory label notes that “for centuries in Europe, [mushrooms] were objects of horror and disgust, connected to witchcraft, poison and decay”. If you ask me, these superstitious medieval peasants had the right idea – I despise mushrooms, cannot eat one without retching, and would happily vote for any politician who vowed to wipe them off the face of the Earth. This, if extreme, is far from being an uncommon attitude, with mushrooms routinely being voted among the most disliked foodstuffs, along with brussels sprouts and marmite. But mushrooms have their fair share of obsessive enthusiasts, too, and whatever else you can say about them, they’re not boring – I can’t imagine enjoying an exhibition about aubergines or artichokes, or anything which actually tastes nice, anywhere near as much.

Balancing the line between art and science, Mushrooms reveals a number of fascinating, if rather troubling, facts about fungi. “There’s been so many discoveries about mushrooms in the last five years – the fact that we share DNA with mushrooms, for instance, or that we have a common single-cell ancestor,” says curator Francesca Gavin of why the exhibition feels particularly timely. Scientists have also, apparently, begun to conceptualise mushrooms as something halfway between animals and plants (if this fact doesn’t send a chill down your spine, you’re made of sterner stuff than me). But Mushrooms has a wider remit than simple biology: “To me, the mushroom has become a metaphor for so many different areas of interest, from anthropology, to science, technology to psychedelia,” says Gavin.

And there’s a political element, too – the exhibition is partly inspired by Anna Tsing’s 2015 book The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. “It’s concerned with matsutake mushrooms and the way they’re picked for a Japanese market in the north-west of America, by migrant workers; it’s looking at ideas around ruins and new ways of looking at capitalism and consumption,” says Gavin. Mushrooms may have a more direct influence on today’s economy, too – according to Gavin, “there’s rumours that the inventor of Bitcoin was a mycologist [the name for biologists who study fungi] and that the currency is built around the structures of mycology”. Bitcoin and fungus certainly share a certain subterranean, secretive quality.

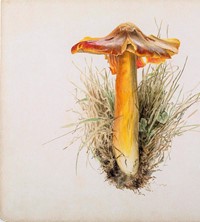

In Britain, the mushroom entered the popular imagination in the 19th century and this was the first time they were viewed as anything other than symbols of decay. This newfound appreciation is beautifully illustrated by a range of drawings by Beatrix Potter, who honed her skills with botanical studies before writing The Tale of Peter Rabbit, which appear in the exhibition. “The major shift against that was the rise of amateur botany and the Enlightenment,” Gavin says. “You suddenly had people looking at nature in a different way and thinking about it as something to be examined and explored. By the mid-19th century, things had really shifted.”

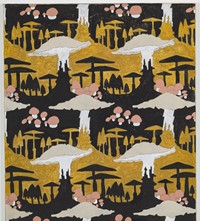

There is also a series of illustrations taken from different editions of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, all of which depict the scene where Alice speaks with a caterpillar who’s huffing shisha while sitting on a giant mushroom. At once indicative of the mushroom’s part in quaint and cosy English pastoralism (Gavin suggests that changing attitudes towards fungi coincided with the rise of the middle class), Alice in Wonderland has become a particularly English symbol of psychedelia, reaching its peak during the hippie movement in the 1960s when the mushroom’s hallucinogenic properties entered the mainstream (Alice in Wonderland inspired a bunch of songs by The Beatles and Jefferson Airplane, which were really about getting high).

The hallucinogenic properties of (certain) mushrooms are an important part in their enduring cultural significance, adding a whole other element that would not be present were they simply a regular foodstuff or decorative plant. Writer, botanist and modern-day mystic Terrence McKenna, for instance, argued that the consciousness-expanding effects of magic mushrooms allowed humans to progress in terms of both culture and evolution – which actually ranks among the least wacky theories about the drug. “There are all these wonderful and creative myths that mushrooms came from outer space or that they were the birth of religion,” says Gavin. “There’s so much to mushrooms, that I understand why people would interpret them in that way. Whether or not they’re true, the narrative is really interesting.”

The exhibition does not shy away from the druggier side of fungi: I discovered, for instance, that mushrooms developed these properties as a way “to dampen insect insights”. (While this may have worked on insects, the evolutionary process clearly failed to consider the threat posed by psytrance enthusiasts and philosophy students.) Psychedelics, which usually involve a visual element, generally hold a greater appeal to artists than more quotidian drugs like cocaine and alcohol. (To test this theory, I googled ‘cocaine art’ and found only a dispiriting selection of images of coke sculpted into different symbols, including the Apple logo and an electric guitar – perhaps the bleakest image ever recorded.) Among psychedelics themselves, magic mushrooms offer a more distinct visual language than others – the mushroom’s distinct shape is more easy to depict than say, the chemical structure of LSD.

But, like other psychedelics, mushrooms also pose an interesting challenge: how do you convey, in words or imagery, an experience which most people agree is impossible to convey? It might be why psychedelic art doesn’t have the most prestigious reputation – when you hear the term, you probably think of garish colour schemes, patterns so intricate they give you a headache, and those images of ethereal figures floating in the depths of the universe, beams of sheer enlightenment bursting out of their heads, which are so annoying they’ve become a widely recognised signifier for intellectual smugness. Psychedelic art, you could be forgiven for thinking, is something you buy from shops in Camden Market alongside legal highs and T-shirts of Donald Trump with the weed symbol tattooed on his face. Psychedelic art, in other words, is not good.

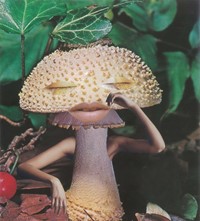

Or at least this is what I thought until I visited the exhibition, which blew a lot of my assumptions about the tackiness of the genre out of the water. The collages of Seana Gavin are particularly impressive, featuring many of the stereotypical hallmarks of psychedelic art – there’s glowing faces, planets, hallucinatory landscapes and imaginary cities. But rather than being garish, her work is also visually restrained and at times even sombre. At the risk of damning it with faint praise, it’s far more tasteful than I’d imagined psychedelic art could be. Many of the works related to psilocybin in the exhibition eschew the visual cliches of psychedelia entirely while still having it as its subject.

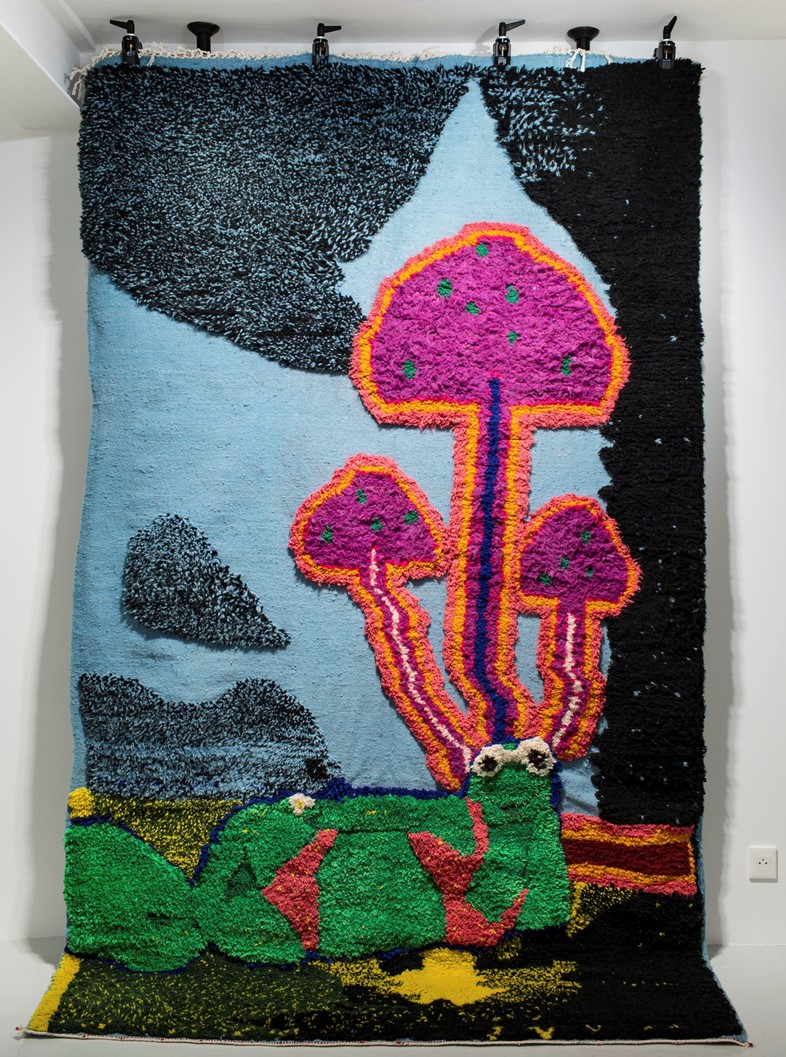

For what may sound like quite a niche subject, the exhibition is thematically broad and also diverse in terms of the media it showcases; there’s video, sculpture, photography and (as the title suggests) design. It’s hard to come away from it thinking that mushrooms are anything other than fascinating. Perhaps the qualities which account for this fascination are the very same qualities which cause some people to be repulsed; the otherworldliness, the eeriness of them. “Artists are looking for ideas from nature which are inspiring and maybe a bit magical. We’re looking for some kind of profundity and pointing towards nature really does that, and particularly so with mushrooms. They’re a signifier of the weird, the magical, the unknown.” I only hope that, in time, I’ll stop having nightmares about them growing sentient and killing us all.