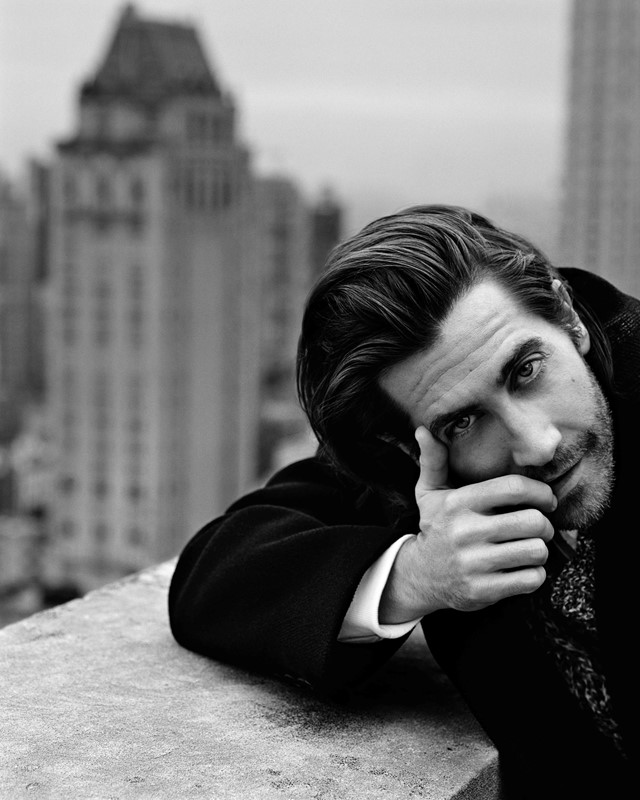

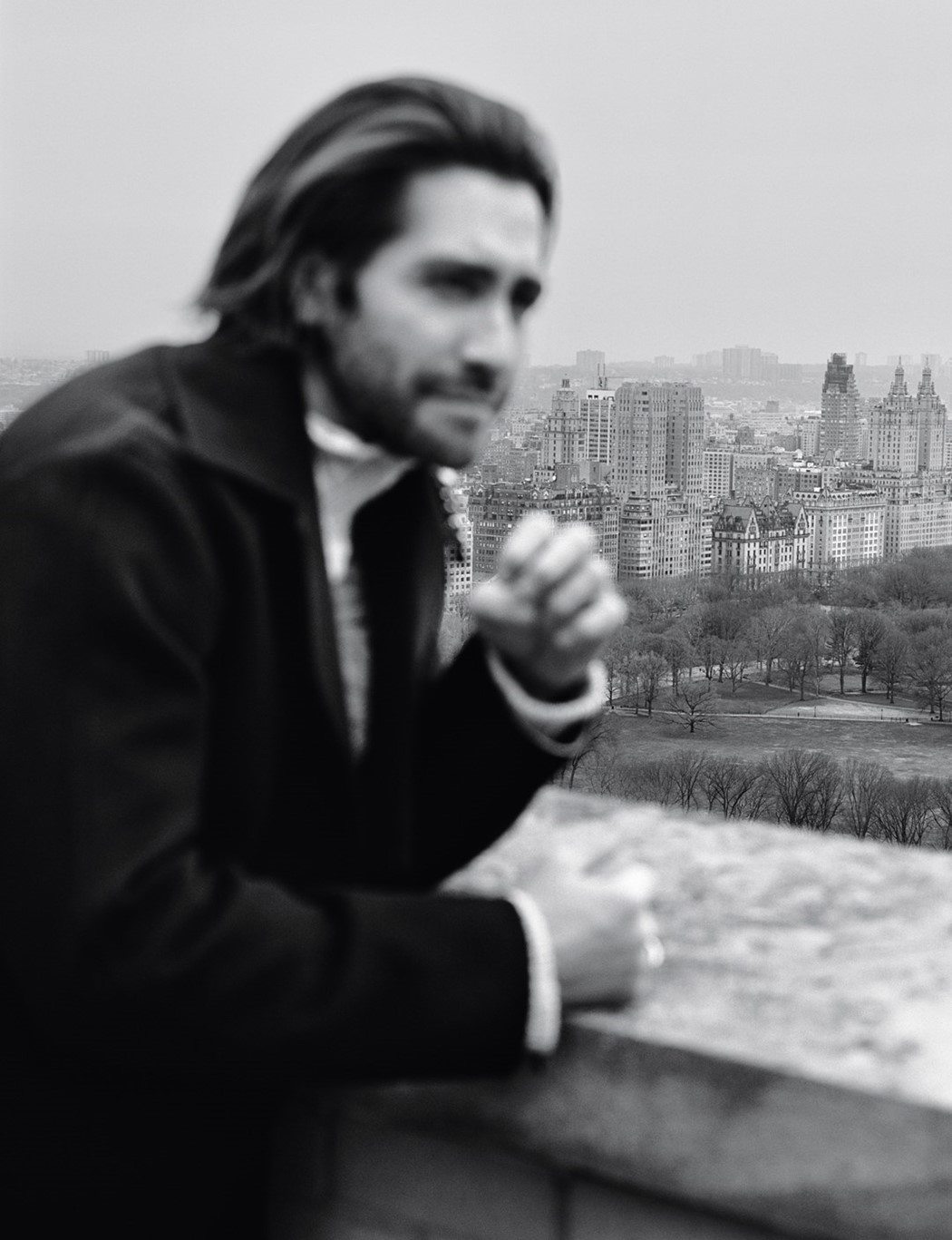

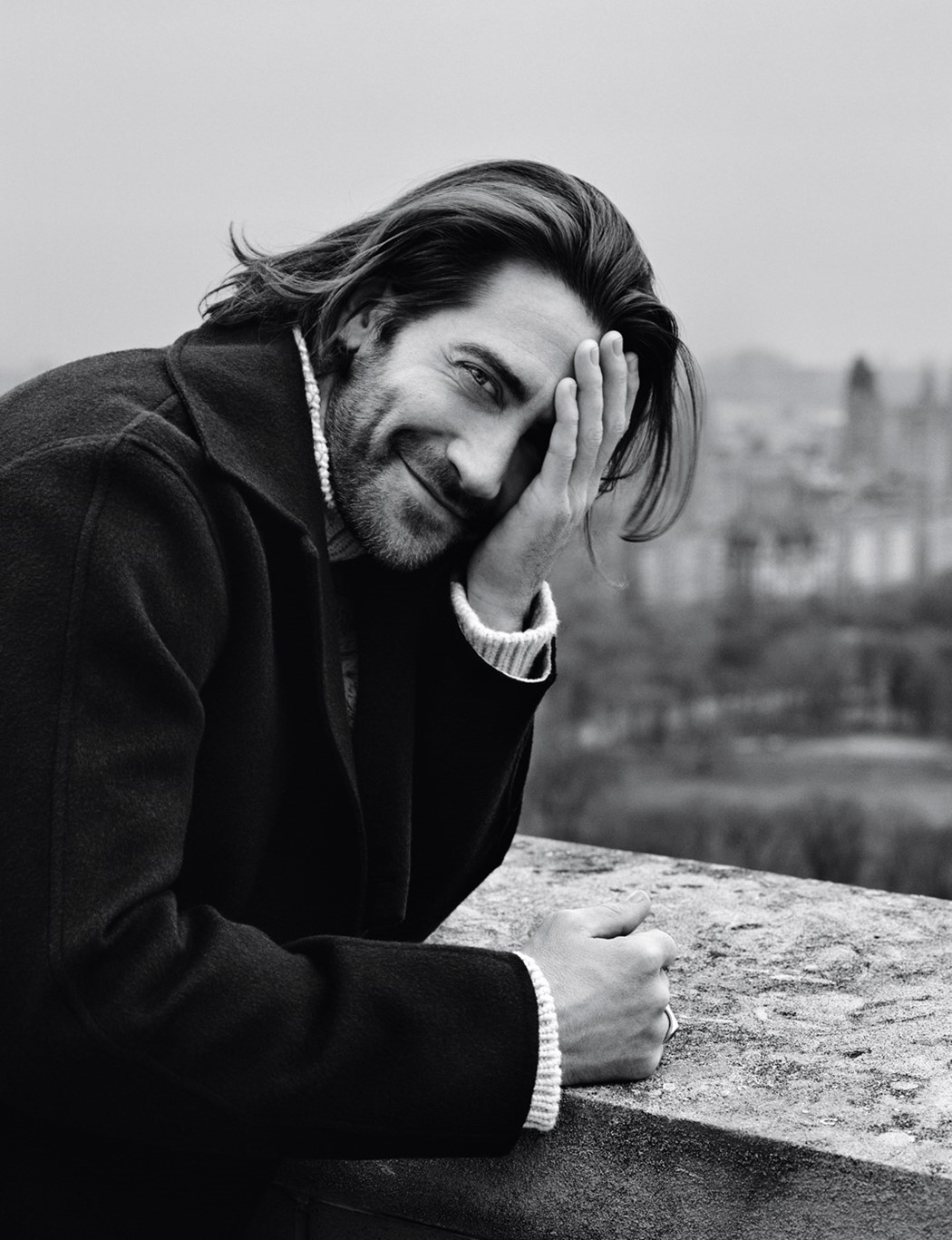

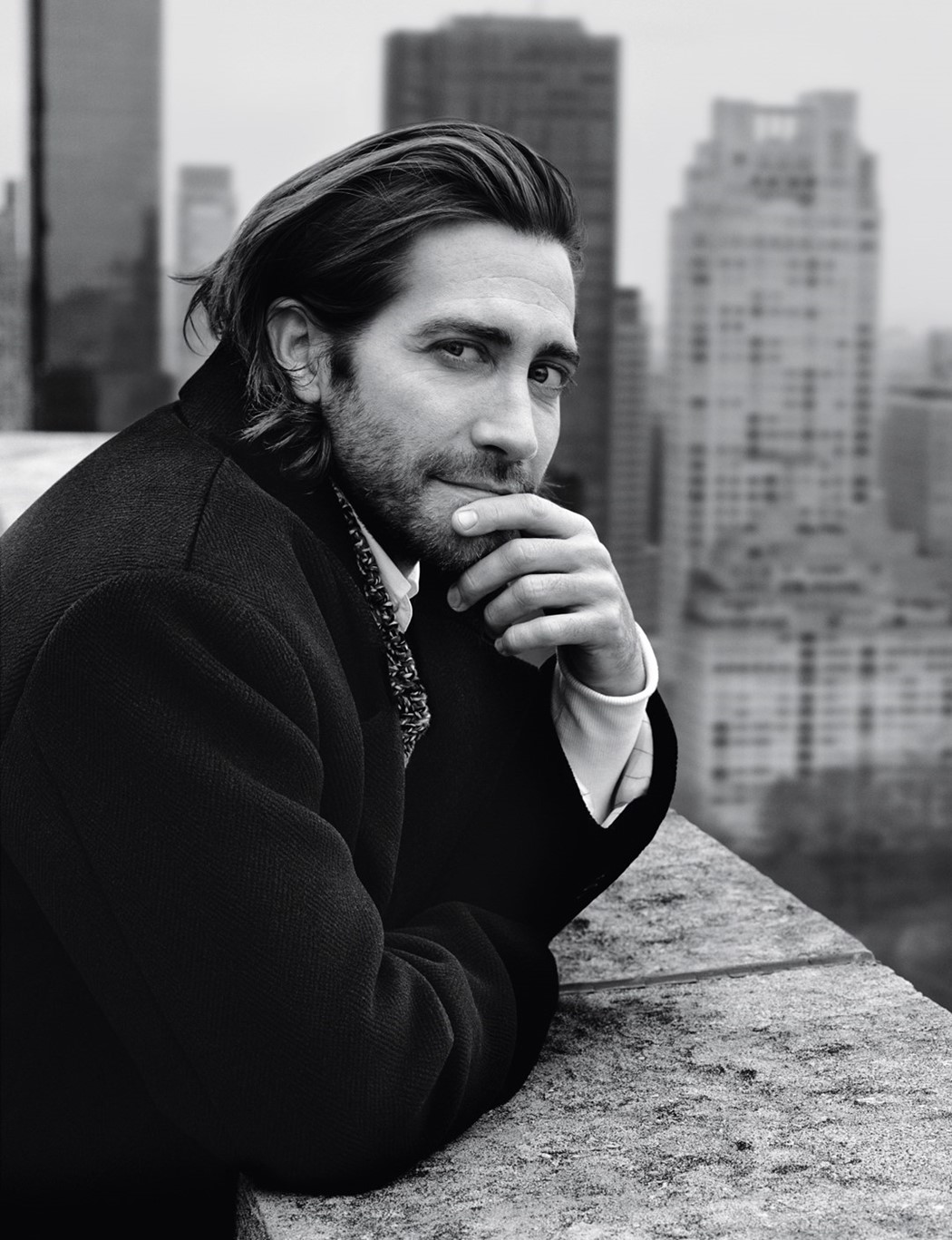

Cover Story: Jake Gyllenhaal Is a Changed Man

- PhotographyAlasdair McLellan

- StylingEllie Grace Cumming

- TextChris Heath

The full shoot: Jake Gyllenhaal for Another Man Summer/Autumn 2020, photographed in New York, February 2020, by Alasdair McLellan, styled by Ellie Grace Cumming and interviewed by Chris Heath

This article is taken from the Summer/Autumn 2020 issue of Another Man:

“I HID IN MY IDEA OF WHAT I THOUGHT AN ACTOR WAS SUPPOSED TO BE, WHAT THEY’RE SUPPOSED TO DO. AND I’M KIND OF LIKE: ‘FUCK IT, I’M NOT LIKE THAT AT ALL’”

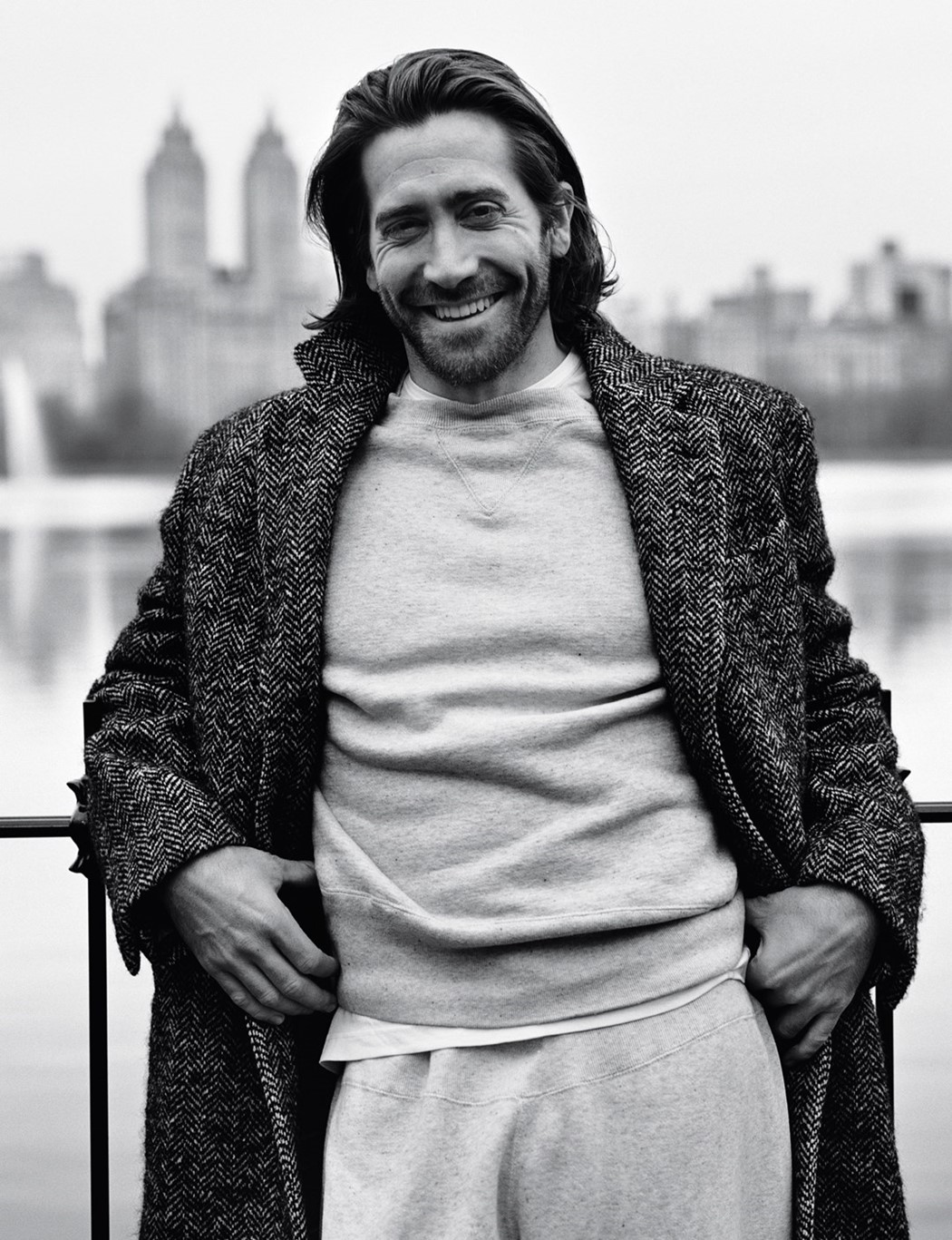

Jake Gyllenhaal will spend a fair amount of the time we spend together today trying to explain how he’s changed. He’ll come at this from all kinds of directions. One moment he might mention how “there’s a preciousness that went away”. Another, he’ll detail how he’s been trying “to take some time, and moments, listen to my own feelings”. Or he’ll compare how he is now to how he was when we last met like this, ten years ago: “All I can say to you is I feel so good where I am in my life. I was so unresolved in so many different ways, searching for things outside of myself, and when we last met I think that was what was happening. Now I’m sort of like: this is who I am, in a lot of ways. This is who I’m gonna be.”

At least part of this relates to an evolution in how Gyllenhaal approaches his acting. He had become known, particularly over the last decade, for roles involving intense preparation often coupled with some kind of notable physical transformation but he now talks of this almost as if it may have been some kind of phase he passed through. It’s not that he’s disavowing what he has done, or even saying that those instincts aren’t still alive within him – “I am super-specific, I am obsessive sometimes when I’m creating things,” he reaffirms – but he is acknowledging how the creative process he embraced may nonetheless, cumulatively, have also amounted to some kind of avoidance.

“I think I’ve hidden a lot,” he says. “Like, ‘I’m gonna hide, and then I’ll create these characters and I’ll tinker in the corner with these ideas...’ I hid in my idea of what I thought an actor was supposed to be, what they’re supposed to do. And I’m kind of like: ‘Fuck it, I’m not like that at all.’”

In truth, conversation with Jake Gyllenhaal is not always the most linear process. There are plenty more explanations and thoughts to come about who he is and who he was, and plenty of other stories and discussions that will offer evidence both corroboratory and contradictory, maybe sometimes even when he doesn’t mean them to, but they don’t always arrive in the most ordered fashion. At one point, in the middle of a stream of broken, half-finished sentences, he apologises, explaining that “this interviewing muscle, talking about myself, has not been used in a while”. Perhaps not, but I think the principal issue is something more interesting. While Gyllenhaal certainly can be eloquent and sharp, at times he is almost charmingly inarticulate, in precisely the way someone is when they are striving to communicate a real experience or thought or feeling for which they haven’t yet worked out a set of neat pre-packaged words. Even if it might sometimes also be a strategy, it still feels like he’s inviting you along on the journey of figuring all this out, rather than just sending you a shiny postcard from the destination.

For instance, when I ask him how or when these recent changes came upon him, he doesn’t have a ready answer. Instead, he starts off on several other thoughts, interrupting himself with various interjections – “when did it happen?”, “what was it?”, “when was it really?” – before settling upon what he believes was at least one of the key moments: his experience with the 2017 movie Stronger.

Stronger, which Gyllenhaal’s company produced, tells the story of Jeff Bauman, who lost both his legs in the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing. Naturally, Bauman was played by Gyllenhaal, who approached the challenge with a characteristic (and impressive) visceral intensity. When the movie was released, Gyllenhaal – who remains deeply proud of the film – promoted it vigorously, the real-life Jeff Bauman often appearing alongside him as an unexpectedly sparky counterpart. But while the movie didn’t sink without trace, nor did it really seem to make its mark in the culture.

Here’s exactly how, sitting here today, Gyllenhaal describes all this, and his subsequent reaction:

“I think I kinda pushed so hard, I wanted that movie to be so excellent. It was a devotion of mine to the guy I played and for myself. I tried everything I could to do his story service – I fought so hard for that movie to get seen, for his story to be appreciated. It felt like a lot of pressure. Because we had made a choice to tell a story about something that was devastating and really real and a person who I became really good friends with. And so I just pushed really hard. It didn’t have the response that I really wished for it. And I think in some ways, in the process of it, learning from Jeff, who I played in that movie, I went, ‘What am I doing? What am I pushing so hard for?’ You know? You can’t pretend these things, you know. You’re never going to play the actual experience. Someone said to me: ‘You’ve lost your imagination.’ And I think I realised that I’d sort of almost lost my imagination. And I went, ‘Well, what the fuck is acting…’ - or, ‘what the fuck is creation…’ – ‘… without imagination?’ And so I went, ‘Okay…’. Like: let’s have a little more fun here.”

Since then, there are two evident ways in which that “a little more fun” has manifested itself in Gyllenhaal’s work. The first has been onstage, in the theatre. Gyllenhaal went straight from Stronger and another film produced concurrently by his company (the family drama Wildlife, an adaption of Richard Ford’s novel) to appearing on Broadway as the lead in Stephen Sondheim’s musical Sunday in the Park With George after only six weeks’ rehearsal. At the time, exhausted, he was worried whether he’d even be able to get through it. But not only did he get rave reviews, more importantly, he discovered some of that a-little-more-fun.

“All it did was feed me,” he says. “And I went, ‘Oh my god, this is my joy, this is what I love.’”

Gyllenhaal also subsequently applied whatever this new principle is to his film work.

“I think the idea of character for me has changed,” he says. “I’ve just let go into the joy of it.” Fortuitously, this shift in approach came along when he was approached to appear in a new Spider-Man movie, cast as the villain Mysterio.

“I’m just taking all the judgement out of it,” he says now, “because it just feels like bullshit. It’s things I love, you know.

I always wanted to be in a superhero movie, do you know what I mean? I mean when, people say, ‘Oh, are you going to play a superhero? Do you want to be a superhero?’ And I’m like, I mean, it depends on who, but, yeah, sure. Yes. I love that, too. And I also do love My Name Is Joe – there’s just fucking nothing like it, and the experience of that movie hits me in the heart and the gut in a way no other movie does. But at the same time, I deeply love and understand Bruce Banner, you know.”

Another way of putting it is that there are certain kinds of praise that can box you in, because the compliment they convey also implies a kind of limitation. “People telling me, ‘Oh, you know, he’s a very subtle actor…’,” Gyllenhaal says. “That was something people said to me all the time. And I was like, ‘No, I’m not!’ I mean, there’s so many other…” He cuts himself off, and instead decides to complete his thought like this: “I mean, I’m smart enough to know that I’m not going to show my whole hand even now. There’s a lot more.”

Playing Mysterio offered Gyllenhaal plenty of scope to show another side of what he could do, an opportunity he took with gusto. Adding an extra layer to Mysterio’s over-the-top playfulness was the fact that the character himself is constantly acting, feigning to be what he is not. Gyllenhaal enjoyed taking advantage of that too. “It was fun for me, because I felt like you don’t really ever know when he’s performing, even when he’s not performing,” he explains. “There were times when I walked off set and I’d go, ‘Man, that wasn’t very good acting… ooooh! Perfect!’ I could throw all that out of the window. Any standards I had, I got to get rid of, and that was really fun.”

“THERE’S A PRECIOUSNESS THAT WENT AWAY”

If there is a new and looser Jake Gyllenhaal, another manifestation of this is his relatively recent presence on Instagram, a turn of events he memorably justified in an American TV interview with the words: “I came to the conclusion that nobody cares about anything any more, so I should join Instagram.”

“Maybe it’s all part of the same thing,” he concedes. “Everybody was taking everything a bit too seriously. Maybe I was taking myself a bit too seriously. I’m actually not that serious. I can be, but I actually am a fool. And it’s a great place to be that. I have a whole group of people who are doing it who might know me and would be interested in getting a little picture every once in a while to see if I had something nonsensical to talk about. So, nobody really cares, you know? And also I just started to say to myself: ‘You’re gonna put your face on a poster for a movie that’s gonna be over the world in different cities on streets, and you’re not going to do a similar thing on this platform that gives you an opportunity to say potentially some interesting things… and potentially some very uninteresting things? Some funny stuff? And play around?’ I mean, look, it doesn’t always make me feel comfortable. But there are things about it that are fun.”

Characteristically, Gyllenhaal pivots in the same conversational breath from this lightness to a recent essay in the New Yorker by the late author and neurologist Oliver Sacks about the perils of the digital age. And from there, somewhat to his bemusement – and perhaps, you may correctly sense, occasional incredulity – we spiral down quite a rabbit hole, beginning like this:

“We are in a very interesting time. You know, where are we headed? How is it that you can look on your end-of-the-week data that Apple spits out at you and realise that you spend three hours on social media somehow? Where the hell did that go? I mean. I’m still flabbergasted I’ve spent 17 hours searching for food on FreshDirect.”

17 hours? In a week?

“It’s not 17, but it’s, like, five to seven. Like, searching for Persian cucumbers. It’s a real search for me.”

You spent five hours in a week searching FreshDirect!

“I like food! I’m into food, and cooking food.”

You do know that shops are available by walking?

“Yes, I do that too. If they calculated all the time I spent looking for groceries, you would know that most of the characters that I’ve played are not characters! Obviously, I just gave myself away. I mean, I do enjoy shopping for food. And I do enjoy searching for whether or not the ingredients are actually sustainable or where they’re from. And it takes some time, you know what I mean?”

And the Persian cucumber – that’s real? I didn’t even know there was a thing called a Persian cucumber.

“What? Yeah, of course. Yes.”

How’s that different from a regular cucumber? “They’re smaller. They’re crunchier. You’re kidding?” I’m not kidding.

“The Persian cucumber and the Japanese cucumber, they’re of a certain size and they’re great.”

And what do you use them for?

“Salad. I don’t search that long for Persian cucumbers, I should admit. I search for other things that potentially you might not ever know. I found a great gingerbread cookie.”

What was special about the gingerbread cookie?

“The taste of it. Is the descriptive enough? Just a classic ginger cookie. A classic, with icing.”

Circular?

“No, rectangular. Looked a bit like a playing card. But large. Soft, yet had a bit of a – as Paul Hollywood would say – a bit of ‘you can still hear the crack...’ or whatever. How have we digressed to this?”

I was told you like these British baking shows. I’m sort of horrified.

“Really? I have watched every one of them. Yes. What is it about them that you don’t like…?”

After we’ve discussed the various pros and cons of cooking shows and the wider world of reality TV formats for a while, Gyllenhaal makes a peculiar and quite interesting observation about the particular world of the The Great British Bake Off: “There’s somewhat of a perversion to it, in that you can never, ever taste nor smell what it is that you see. You can watch people build Legos, you don’t need to smell Legos. You don’t need to taste them, you can watch it. But when you watch somebody build like a tiramisu… You’re never gonna taste that! No. You’re never gonna taste that! And all you have is someone describing it to you. You know, it’s Mary Berry and other hosts that tell you, and they’re experts, and that’s great. But there’s something about it that I think, particularly as a Brit, you might find very interesting.”

You’re suggesting that there’s something pleasingly masochistic in that absence?

“Yes. Yes. And, at the same time, also just wonderful to watch, I mean, you’re in the English countryside, you’re in a tent. You know? It’s great.”

Oh my god.

“I know. I’m sorry. Maybe you shouldn’t have taken this interview.”

“EVERYBODY WAS TAKING EVERYTHING A BIT TOO SERIOUSLY. MAYBE I WAS TAKING MYSELF A BIT TOO SERIOUSLY. I’M ACTUALLY NOT THAT SERIOUS. I CAN BE, BUT I ACTUALLY AM A FOOL. AND INSTAGRAM IS A GREAT PLACE TO BE THAT”

Gyllenhaal has spent substantial chunks of his adult life in Britain (most recently, filming Spider-Man: Far From Home) and will be back for several months this summer when Sunday in the Park With George is reprised at the Savoy Theatre in London. (It’s a musical, incidentally, that pivots off the life and work of the pointillist painter Georges Seurat.) Gyllenhaal says he likes the British acting tradition and craft and shorter work days, and the dry sense of humour: “There’s just so many things I love. And I’ve also been very embraced there since I was really young. You know, the way my brain works, my mind works, I felt more embraced there than even here.”

I ask him, conversely, what drives him crazy in Britain.

“I think, in the end, how different we are,” he replies. “In the end sometimes I just say: can you please just tell me how you feel?” He goes on to complain about the lack of cooling systems or fans in the summer (“it’s just a suggestion”) and the way British people refuse to believe anyone else can make a decent cup of tea (“just not true”) and the prejudice that no Americans can do a passable British accent.

Just going back to the first thing: you do know we’re never going to tell you how we feel?

“No, I know that. I know. Believe me, I’m very aware.”

There’s a lazy love in our culture – not just in Britain or America, but more within global popular culture at this point – for a specific kind of story about the famous, one that shows them to be self-obsessed and overcome with self-regard. It seems that many of us – too many of us – wish such stories to be true. (I see it as a subset of a wider, generally-unexamined resentment towards the famous for their presumed conceit in thinking that we’re interested in them, a resentment principally held by those most keenly interested in them.) However much Jake Gyllenhaal may try to separate himself from this kind of world, he is not immune, and a mean-spirited classic of the genre appeared in the American tabloid the New York Post on 26 April, 2019. Its headline was Jake Gyllenhaal’s favorite art is of himself and the story read, in part, like this:

A Page Six spy recently overheard a conversation in a downtown art framing store between a collector – who had been lucky enough to get a portrait of himself done by a favorite artist – and the store owner.

When the guy asked the owner if it seemed too vain to get a picture of himself framed, the owner reassured him by saying, “Jake Gyllenhaal comes in all the time and I’ve never framed something for him that’s not a picture of himself.”

Perhaps understandably, Gyllenhaal doesn’t seem over-exuberant when I mention this, but I’m glad I do, because it’s sometimes when people are slightly on the back foot that they provide the most eloquent and heartfelt expression of how they actually feel and think. First, at my request, Gyllenhaal addresses the specifics, but his answer will grow from there.

“Oh god. What do you want to know about a nonsensical story? So what I think happened is – because I can safely say here that I don’t have any framed photographs of myself in my apartment – is that I have a production office, and at the production office we have posters of my movies.”

Which is not that weird.

“I mean, some people may think it. But it is what happens. And so I assume what happened is that when they were framed, that’s what someone’s said. I mean, there’s no other way it could be anything else.”

But is it, consequently, offensive? Because it certainly plays into some kind of stereotype.

“I’m a big boy. You know, people like to write many things. In truth, you can’t stop people from doing whatever it is they want to do. I’m of the firm belief that creating is much harder than destroying. And, you know, all of us have a three-year-old in us who likes to build the Lego and then kick it right over. But I also believe when we’re grown-ups, we should have a part of us that says, ‘Let’s take the tough time to create, as opposed to destroy.’ It’s nonsense. To me, nonsense is nonsense. Like I said: frankly, I don’t think anybody really cares. I wouldn’t have even known about it if I hadn’t gotten a phone call from the people I work with. I just thought: it’s just not true, so why are they even going to say that? I mean, let’s go to my apartment! I also believe that people ultimately at some point know something is nonsense, and who someone is, and who they show themselves to be.”

While we’re at it, here’s another headline, one published only a few days before Gyllenhaal and I meet: Did Jake Gyllenhaal Endorse Bernie Sanders Through His Cat’s Insta? The story refers to a post from the account purportedly belonging to a cat called Ms Fluffle Stilt Skin – who many people online seem to believe, for reasons which are not entirely clear, belongs to Jake – in which the cat in question is pictured in front of the candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination speaking on a TV screen. The post’s caption is “I’m feline this guy”. If there is a way to have a conversation about this that is not surreal, we fail.

Did you see the story?

“I’ve been told about it. I don’t have cats.”

It seems people really think this is true.

“One of my favourite things about Fluffle Stilt Skin, a cat that I do know…”

You do know this cat!

“I do know the cat. And she’s a magnificent cat. And, as every American, she is entitled to endorse whomever she would like to endorse.”

So how are you brought into this?

“I will say one thing: you will get no clarity from this situation that you’re hoping for. Except to tell you that I have a dog. I’m allergic to cats.”

And, for the record, you have made no endorsement?

“No.”

Another way that Gyllenhaal addresses his recent trajectory is through the prism of manhood. “The idea of being a grown-up, of being a man was, at the time when we talked last, something I was searching for,” he reflects. “I’ve spent many years trying to understand what that is. Like, movie after movie, life experience after life experience, going to certain extremes, to say, ‘Oh, is it in the physical world? Is a man who holds a gun...? Is a man who gets in a boxing ring...? Is a man who falls in love with another man?’ What is masculinity? And without knowing it, I think that’s what I was searching for.”

What I believe he is now saying is that instead of trying to learn about being a man by inhabiting all these different versions of manhood in his acting roles, he is just taking some time to try to be.

“It’s been really lovely,” he says. “Much more space for my mind to wander, and much more time to just say, ‘Oh, how did that make me feel?’

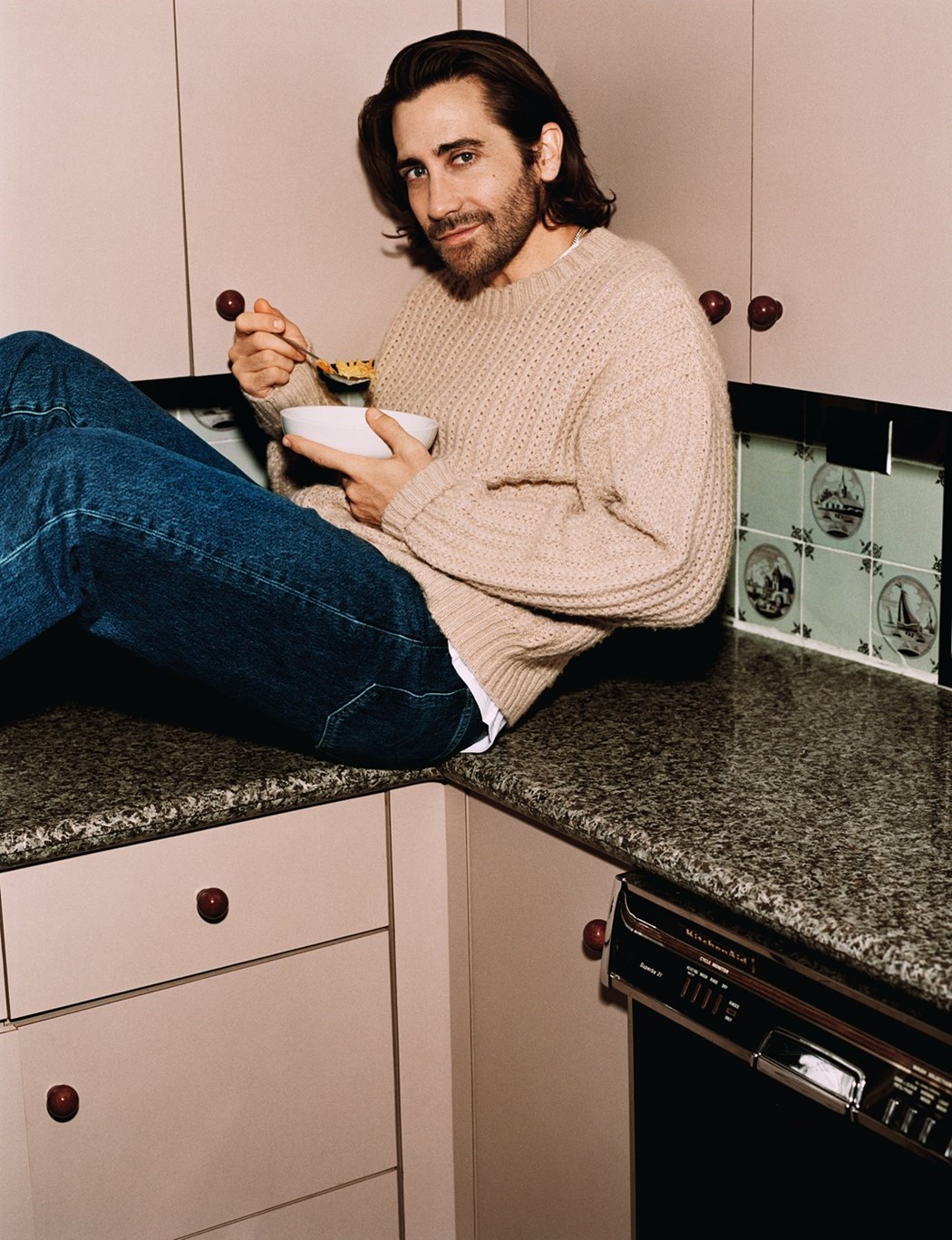

Although he has been on stage, Gyllenhaal hasn’t been on a film set to shoot a scene since the last day of the Spider-Man shoot in September 2018, and he says that he has no firm plans as to when he will next do so. Instead, he says he’s been reading, cooking, particularly for his nieces (“They like my cooking, you know”), letting his hair grow (“you sort of go: ‘why not?’”), travelling, both to see his family in California and further afield. He mentions a recent trip to Bhutan, one that seems to have been undertaken on almost a whim – “Someone had said, ‘Oh, it’s a nice time to go to Bhutan.’ And I thought, ‘Where is Bhutan?’ I knew it was near India, I just didn’t know exactly where” – but which he describes as an incredible experience. He tells me about having tea at the top of a three-hour hike next to a melted glacial lake, and about another hike up to a temple where a monk has lived for 35 years. “I had tea with him too,” Gyllenhaal says. “And some very stale crackers.”

At the same time, in a different way Gyllenhaal is busier than he has ever been. He has a production company, a serious one with 30 projects in development (“some of which I’m in, some of which I’m not”), and four films in which he doesn’t star either in post-production or awaiting release. The company is called Nine Stories, a name which in part is an accidental relic, inherited from the corporation name Gyllenhaal needed for business reasons when he started out, and which the young Gyllenhaal had taken from a book he loved deeply, the short story collection by JD Salinger. When he set up this current production company, Gyllenhaal tried countless other names but, failing to find one that seemed to work, eventually went back to this. Still, even setting aside his slightly mystical thoughts about the number nine, he does now have a rationale for it.

“I think, also, if you can make nine great stories in a lifetime, or tell them,” he suggests, “you’re good to go.”

And how far in do you think you are?

“I think I have been in them. I have yet to make any.”

But that’s the plan?

“Yeah.”

“THE IDEA OF BEING A GROWN-UP, OF BEING A MAN WAS, AT THE TIME WHEN WE TALKED LAST, SOMETHING I WAS SEARCHING FOR. I’VE SPENT MANY YEARS TRYING TO UNDERSTAND WHAT THAT IS. LIKE, MOVIE AFTER MOVIE, LIFE EXPERIENCE AFTER LIFE EXPERIENCE, GOING TO CERTAIN EXTREMES, TO SAY, ‘OH, IS IT IN THE PHYSICAL WORLD? IS A MAN WHO HOLDS A GUN...? IS A MAN WHO GETS IN A BOXING RING...? IS A MAN WHO FALLS IN LOVE WITH ANOTHER MAN?’ WHAT IS MASCULINITY? AND WITHOUT KNOWING IT, I THINK THAT’S WHAT I WAS SEARCHING FOR”

When Gyllenhaal talks about all the stuff he’s understood and resolved since we last met ten years ago, he can make it sound as if things might now be sorted and settled. I don’t imagine that they are. I love that he feels he’s worked all these things out, and I feel he’s sincere in saying so, but I have a pretty strong hunch that if we meet again in ten years he’ll have worked out a whole load of new stuff.

What’s maybe more significant in the long run is the spirit and energy and inquisitiveness he brings to it all. When you listen to Gyllenhaal talk – for instance, to give just one example, when he explains how he needs to be “working with people who’ll say, ‘Yes, you can try all these strange things, and we’ll cut them out anyway if we don’t like them, but go ahead’” – you get a sense not just of what a tonic it may be to work with him but how maddening it often probably is too, but you also get a sense that he’s genuinely committed to a voyage of honest exploration, one not focused on preening his ego.

We’re pressured to admire people who have it all together, but I’m quietly always more interested in, and impressed by, the others: the ever-curious, not the already-certain; the ones with lots of questions, forever looking for something, not the ones with all of the answers who are sure they’ve found it; the right kind of mess, not the wrong kind of perfection. And it feels like Gyllenhaal may be one of those.

Just before he leaves, we talk about a key moment in his past, Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain (2005), in which he appeared alongside Heath Ledger. Gyllenhaal told me ten years ago that he couldn’t watch it, and I ask whether that’s still the case. He says it is. He talks – then and now – about the film as though it was something he was fully committed to but which nonetheless in some ways existed beyond his control and understanding. “There are things you’re chosen for – a quality, an essence – and Ang did that. And it’s still a mystery to me. And something that Heath and I shared: that it was a mystery to us at the time.”

I mention to Gyllenhaal that when I recently watched back old TV interviews from the time, I was jolted by how homophobic a lot of the banter seems, even when it was intending to be the opposite: gay cowboys, it’s all a tremendous joke. This reminds him of something.

“I mean, I remember they wanted to do an opening for the Academy Awards that year that was sort of joking about it,” he says. “And Heath refused. I was sort of at the time, ‘Oh, okay... whatever.’ I’m always like: it’s all in good fun. And Heath said, ‘It’s not a joke to me – I don’t want to make any jokes about it.’” I say how smart of Ledger that seems, in retrospect. “Absolutely,” says Gyllenhaal.

His phone keeps pinging, and he clearly needs to go, but even as he prepares to do so, this train of thought leads him to reflect further on occasions, like the filming of Brokeback Mountain where, as he puts it, “the life experiences of them are so deep that no matter how powerful the movie is to many other people, or what it means to them, it means something completely different to me.” He mentions, as a second example, Southpaw, and then suddenly, unexpectedly, Jake Gyllenhaal is talking about the very first day he stepped in front of the camera, at the age of ten playing Billy Crystal’s son in the amiable fish-out-of-water comedy City Slickers. He starts describing the whole scene: feeling the unnatural temperature of the 10K lights illuminating the classroom through a window, and how there was a hallway that was dark, and how there was a scrim blocking off people who didn’t need to see, and how in awe he felt, stepping into that sacred space.

“I’ve seen that scene sometimes,” he says, “and I see that little boy, and all I remember is that other side, that perspective. And it’s so deep in me.”

Gyllenhaal doesn’t say where he is going, but if I now imagine he has a quiet day ahead of him, a little reading, searching online for produce to cook for dinner before putting on some meditative jazz and going to bed, I’m wrong. Though he doesn’t mention it, he has a rehearsal to get to.

The next evening’s episode of the TV show Saturday Night Live is hosted by the comedian John Mulaney. One sketch, set in a New York airport, finds a variety of increasingly outlandish characters, most played by cast members from the show, singing parodic air-travel-related versions of famous songs from musicals. Towards the scene’s end, a man strolls onstage in striped pyjamas – a man greeted, as soon as the audience realised that it is Jake Gyllenhaal, with delighted it’s a famous person applause. He proceeds to sing a song, one originally from the musical Wicked but now about how happily Gyllenhaal’s character submits to the attentions of airport security inspectors, however invasive. As he approaches the song’s climax – “you can search way up in my cavity!” he booms – Gyllenhaal lifts off from the ground, and flies above the stage on wires, before disappearing high into the wings, off away towards whatever strange fun lies ahead.

GROOMING Losi at Honey Artists SET DESIGN Nicholas Des Jardins at Streeters PHOTOGRAPHIC ASSISTANTS Lex Kembery, Simon Mackinlay STYLING ASSISTANTS Jordan Duddy, Isabella Kavanagh, Ian McRae SET DESIGN ASSISTANT Gautam Sahi PRODUCTION Pony Projects PRODUCER Leone Ioannou PRODUCTION COORDINATOR Daniella Fumagalli PRODUCTION ASSISTANTS Zach Berry, Cristina Bartley-Dominquez POST PRODUCTION Output London

The Summer/Autumn 2020 ‘High Art Pop Culture’ issue of Another Man is now on sale internationally. Head here to buy a copy.