Cecil Beaton’s Photos of the Bright Young Things and Britain at War

- TextMark Simpson

From Bright Young Thing and documenter of London’s lost generation of the 20s to a documenter of a new generation who would lose their lives in the Second World War, this is just one slice of Cecil Beaton’s remarkable life through photography

This article is taken from the Summer/Autumn 2020 issue of Another Man:

In a world saturated with social me-dear surveillance and suffused with surplus selfies, being ‘interesting’ becomes ever-more compulsory – just as it becomes ever-more elusive. Not just for artists in this brave new connected, visual, attention-seeking world, but for civilians too.

Little wonder that Cecil Beaton, a man who essentially invented himself and his astonishing career with a portable camera loaded with his ambition and longing, one of the brightest of his bright young generation of the 1920s, has become more famous, not less. As we plough relentlessly into a 21st century that he anticipated in many ways, long before his death in 1980, I suspect ours is a world he would be as much horrified as impressed by.

He was by his own admission, “driven by the visual”, and claimed not to have read a book before he was 18, which makes him sound almost millennial. But luckily for posterity, he also had a wicked way with words. His books and waspish diaries contain many timeless quips:

“What is elegance? Soap and water!” “All I want is the best of everything and there’s very little of that left.” “Perhaps the world’s second-worst crime is boredom; the first is being a bore.” And my personal favourite: “Never in the history of fashion has so little material been raised so high to reveal so much that needs to be covered so badly.”

But perhaps the most oft-quoted Beaton aphorism in our e-Darwinian age is his scornful advice to “Be daring, be different, be impractical, be anything that will assert integrity of purpose and imaginative vision against the play-it-safers, the creatures of the commonplace, the slaves of the ordinary.”

Beaton was undoubtedly one of the most interesting men who ever lived – and the life he lived is itself a kind of fantastic fairytale, albeit a lonely one without a happy ending. His advice, then, is certainly to be taken seriously, but I harbour some scepticism about how fully people who quote him on their Instagram and Patreon pages understand what being ‘interesting’ really involves. Where it comes from. And what it costs.

The 19th-century French writer and flâneur Charles Baudelaire did. He believed that the dandy – and Beaton most certainly was one, even if he didn’t describe himself as such – has “no profession other than elegance ... no other status, but that of cultivating beauty in their own persons ... The dandy must aspire to be sublime without interruption; he must live and sleep before a mirror.”

Beaton not only lived in front of the mirror, taking many self-portraits, some in drag, and maintaining an impeccable dandified image most of his life, but he went behind the mirror as well, photographing and capturing the mysterious charms of beauty in his many celebrity portraits. Beaton accessed a beautiful dreamworld betwixt life and death that he never quite left. He was perhaps the last great dandy and romantic, which is the loneliest kind of life. But he nevertheless performed a great public service

Interviewer: Your mother wasn’t able to help you in this particular difficulty?

Beaton: No, no one could help me. It was up to me to find the sort of world that I wanted.

Face to Face, 1962

Cecil Walter Hardy Beaton was born in 1904 into a prosperous Edwardian middle-class family in Hampstead, a leafy suburb of London. He was the product of true theatrical romance: his mother Esther was a Cumbrian blacksmith’s daughter who was visiting London when she fell in love with his father Ernest, a timber merchant, after seeing him onstage in the lead role in an amateur dramatic production.

True to his origins, as a boy Beaton took to hanging around outside theatres, admiring and losing himself in the pretty posters marketing the actresses of the day. Using a Box Brownie camera he was given at the age of 11, he dragooned his pretty, blonde younger sisters, Barbara (Baba) and Nancy, into recreating that world: a fantastical, stage-y, lushly artificial dreamworld that he was, almost by sheer wishful thinking, later to people with actual starlets and some of the century’s greatest celebrities.

Beaton, who went on to photograph so many famous women with an eye that was more conspiratorial than analytical, began his lifelong love affair with the camera at the instruction of a woman – his photography-enthusiast nanny. Beaton’s gaze was not exactly what you’d call ‘male’. It was rather more ambiguous than that.

“My mother’s dressing table drawer of powder, rouge and mascara held an uncanny fascination for me,” he wrote. “One day, I stole into her bedroom and painted my face. My father caught sight of me. He became so enraged that I was locked in my bedroom.”

Neither was the world of men, or boys, Beaton’s. He had a difficult and distant relationship with his father and “the noise of laughter in the billiards room” as he called it later. He hated his first (boys only) school, Heath Mount, not least because he was mercilessly bullied by fellow classmate Evelyn Waugh, who probably found Beaton’s unabashed sissiness a personal affront. Which is a kind of distinction in itself – if the future author of Decline and Fall and Brideshead Revisited picks on you at school, you must have something about you. In fact, Waugh proved to be a thoroughly dedicated follower of Beaton’s, and continued to bully him and in effect shadow his career into adulthood and old age – and Beaton returned the compliment.

“EVELYN WAUGH IS MY ENEMY. WE DISLIKE ONE ANOTHER INTENSELY. HE THINKS THAT I’M A NASTY PIECE OF GOODS, AND, OH, BROTHER, I FEEL THE SAME WAY ABOUT HIM” – CECIL BEATON

Others were enchanted in a more convivial fashion. The writer Cyril Connolly, who attended Beaton’s next school, St Cyprian’s in Eastbourne – along with George Orwell – wrote in his autobiography of being overwhelmed by the beauty of Beaton’s singing at school concerts.

At Harrow, Beaton found himself bored and unable to fit in with the laughter in the billiards room. He cheered himself up by dressing up in theatrical costumes with other alienated boys and taking photographs – escaping into the wonderland of his Box Brownie. After going up to Cambridge in 1922, he spent most of his time and energies on the Amateur Dramatic Club, failing his exams and leaving without a degree in 1925, much to his father’s consternation.

He had however been submitting his photographs to various publications, sometimes under an alias enthusiastically recommending the work of ‘Cecil Beaton’. Eventually in 1924 he succeeded in selling a photo of the Duchess of Malfi to Vogue. It seems entirely Beatonesque that his first celebrity portrait was in fact a slightly out-of-focus photo of a male student in drag – shot outside the gents’ lavatory of the Cambridge ADC. After all, illusion and artifice are the heart of glamour.

Beaton’s big break however was falling in with the ‘Bright Young Things’. This was not left to happenstance – not only had much of his life been preparation for this, he mercilessly worked his contacts to get introductions to the Sitwells – siblings Osbert, Edith and Sacheverell – who were Bright Young Thing royalty.

So-named by the tabloid press, the Bright Young Things were a group of bohemian aristocrats, socialites, poets and artists, who came of age during or just after the first world war, and whose response to the loss and horror of that conflagration was to embrace hedonism. Celebrating pleasure, art and beauty – and being alive – they held legendary champagne-and-drug-soaked parties including hijinks such as elaborate treasure hunts through night-time London. In addition to the Sitwells, leading figures included the poet John Betjeman, the critic Harold Acton, the novelist Nancy Mitford and the painter Rex Whistler. Evelyn Waugh of course hated them, and satirised them in his 1930 novel Vile Bodies.

“THERE IS ALWAYS SOMETHING DRAMATIC ABOUT THE JOB OF PERMANENTLY RECORDING THE FEATURES OF A HUMAN BEING, IT IS THE THEATRE BROUGHT TO EVERYDAY LIFE” – CECIL BEATON

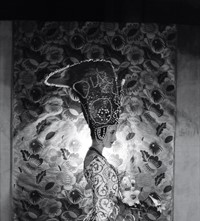

Beaton, with his effeteness, sharp wit, insatiable love of aristocracy and dreamy camera skills, was a hit and became in effect the court photographer of the group. He also found a patron and muse in the Brightest ‘Thing’ – Stephen Tennant, the ethereally pretty, heroically vain, lipstick-and-pancake-wearing, gold-dusted, dyed-haired ‘It’ boy of the 1920s. (And also, arguably, of the 1980s, when, thanks to Beaton’s photo portraits, half the Blitz club wanted to be him.)

Tennant’s older brother Edward, a promising poet, had been killed in the first world war, aged 19. The younger Tennant, who would be an inspiration for Waugh’s dissolute, decadent, doomed beauty Sebastian Flyte in Brideshead Revisited was in many ways collateral damage.

Aesthetically, Tennant was an even more epicene, more elegant – and more aristocratic – version of Beaton. He was what Beaton aspired to be – so Beaton knew exactly how to capture him. His hypnotic other/unworldliness shines out in Beaton’s photos. In some of the photos he took of them together they look like fairy twins – or satanic angels.

With the help of Osbert Sitwell, Beaton was able to put on his first exhibition at the Cooling Gallery in 1927, featuring many of his photos of the Bright Young Things – including his famous portrait of angular Edith Sitwell posed as a gothic tomb (Edith was to remain a close friend until her actual death in 1964). Beaton’s reputation as the most fashionable photographer of his generation was sealed.

In 1928, with the wind in his sails, Beaton steamed to New York with the unassailable conviction that America would throw itself at his feet. But initially America proved somewhat impervious to his charms, especially after he made a remarkable appearance on film in which he criticised, looking and sounding every inch the faggy limey dandy, New York women for not looking like English aristocrats. (At the end, in a hilarious touch – Beaton was both very funny and very sincere – he affectedly studied his fingernails/claws).

After a year of “difficulty” he landed himself a lucrative contract with Vogue magazine, where he worked as a highly successful photographer for the next decade, using his sense of theatricality, wit, artifice, love of the surreal (e.g. the famous head-in-a-hatbox photo) and taxidermist’s skill, to turn selling into an art form and help invent fashion photography as we know it today. Fashion, after all, presents us with a through-the-looking-glass dreamworld we can inhabit – for a price. Beaton proved the perfect spirit-guide to that world, one he had been inhabiting as often as possible since his youth.

He also travelled the globe photographing celebrities such as the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, Gary Cooper, Marlene Dietrich, Jean Cocteau, Coco Chanel and Pablo Picasso. Beaton was queen of the world – so it was fitting that he was appointed court photographer to the royal family in 1937. Queen Elizabeth (the future Queen Mother) took to the witty, catty, stylish young man, and he took photos of her in the gardens of Buckingham Palace styled almost as an Edwardian actress, in a white (in fact pale pink) dress complete with parasol that helped turn her into a camp icon.

But then, in 1938, disaster struck. Entirely self-inflicted disaster. He inserted, in tiny but fatally legible print, anti-Semitic words and phrases into a Vogue collage of New York society figures. A huge scandal erupted, and he was forced to quit Vogue and New York in disgrace, his career in tatters. He was profusely apologetic, and asserted he was not anti-Jewish and was “violently hostile to Hitler”.

Why did he do it? Beaton said he didn’t know and seemed as much baffled by it all as he was remorseful. In hindsight it seems a product of his childish, bitchy sense of humour – and his English snobbery, acquired from the English aristocracy, who were known for their casual anti-Semitism.

He was however to make amends in the most spectacular and convincing fashion, in a way that transformed him and his legacy, marking his late arrival into adulthood – and demonstrating how true dandyism requires great courage.

After the outbreak of war in 1939, he was offered the job of photojournalist by the Ministry of Information. He was to travel to fronts all over the world, to China and the Middle East, find himself in crossfire and plane crashes, taking photos that captured the intimate personal impact of this global war in a style as direct and immediate as his previous photography was artificial and dreamy. His talents were now enlisted for propaganda rather than fashion – for capturing ordinary men and women in the service of their country, rather than pampered starlets in the service of glamour. And what glorious propaganda he made!

It was in particular his photos of the war on the Home Front – the land girls, the Blitz, the Battle of Britain pilots of 1940 – that rehabilitated Beaton. His famous portrait of three-year-old Blitz victim Eileen Dunne in a hospital bed, head bandaged, clutching her teddy bear and looking reproachfully into the camera, appeared on the cover of Life magazine and helped mobilise public opinion in the US on Britain’s side.

His portraits of young RAF airmen as they waited for the scramble bell to toll them into the skies above England to face the Luftwaffe and death were the grounded counterpoint to his Bright Young Things period. But then, the 1920s generation shaped by the apocalypse of the first world war had scrambled and were now taking on Hitler and the second apocalypse.

Nancy Mitford became an ARP driver for a while, worked shifts at a first-aid post in Paddington and looked after evacuated East End families at her London home – and denounced her fascist-sympathising sister Unity. Harold Acton joined the RAF. Rejected as unfit for military service, John Betjeman worked for the films division of the Ministry of Information. Rex Whistler served in the Guards Armoured Division and was the first member of his battalion killed in the Normandy campaign. For all their decadence, the Bright Young Things were made of stern stuff, and when the time came, many of them did their duty and more.

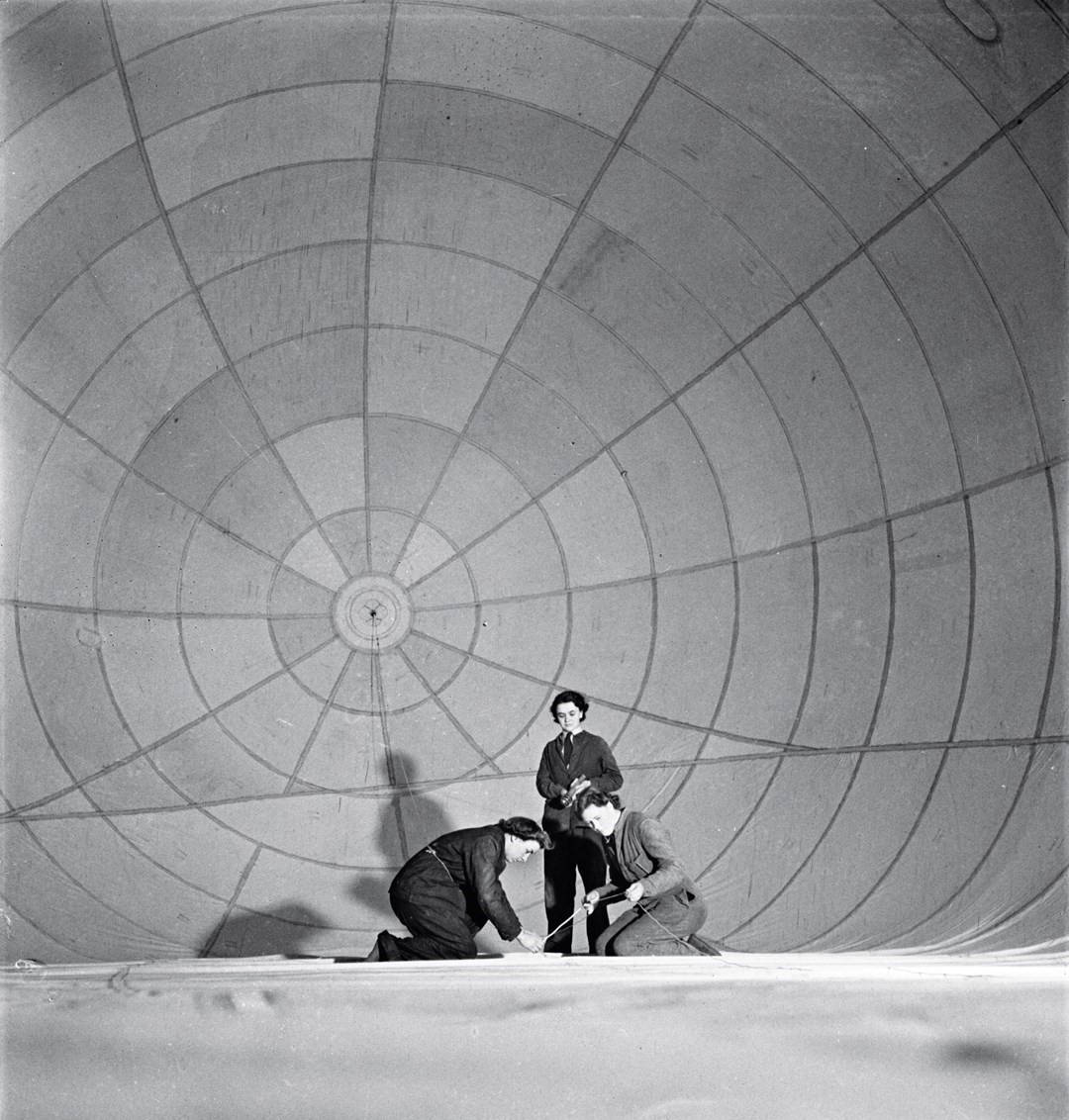

Beaton did his duty to his country and himself. The theatrical aspect, the drama that Beaton always sought and often found in his photos, was provided by the stage – and apparatus – of war, the struggle against Nazism, and the threat of death, his genius for composition finding a new, fresh, much larger canvas. The war-factory women dwarfed and yet centred by the geometry of a deflated barrage balloon. A bow-tied Winston Churchill surrounded by the weighty paraphernalia of the War Cabinet, frowning resolutely into the camera.

“I HAVE NEVER BEEN IN LOVE WITH WOMEN, AND I DON’T THINK I EVER SHALL BE IN THE WAY THAT I HAVE BEEN IN LOVE WITH MEN. I’M REALLY A TERRIBLE, TERRIBLE HOMOSEXUALIST AND TRY SO HARD NOT TO BE” – CECIL BEATON

There is also a refreshing, arousing egalitarianism in Beaton’s wartime photos, his snobbery short-circuited perhaps by his sexuality. His male subjects gaze into this effeminate man’s lens in a way that is entirely modern and alive: intimate. There is almost a “got a light, mister?” pick-up quality to some of them at a time of course when, as for most of Beaton’s life, any and all male homosexuality was completely illegal, if rather common. The images are even more poignant and affecting when we consider that in some cases this may have been the subject’s last ever photograph.

Beaton himself died in his own bed, aged 76, at his home in Wiltshire in 1980, after a highly successful postwar career immortalising a new generation of Hollywood stars, such as Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor and Audrey Hepburn. He won three Oscars himself for his inspired costume work on films such as Gigi and My Fair Lady and was the subject of a 1971 tribute documentary by the photographer David Bailey, featuring Mick Jagger, Twiggy and David Hockney.

Knighted in 1974, Beaton lived long enough to see his work and legacy fully acknowledged, and also to see homosexuality (partially) decriminalised in 1967, meeting and basking in the adulation of a new generation of young people influenced by his work and much more relaxed about male homosexuality. He even made it on to Desert Island Discs in 1980.

But he died alone and by many accounts unhappy, both with being alone and being old. In his bedroom were found three of his photos – two were of male lovers – art collector Peter Watson and Olympic fencer Kinmont Hoitsma – who looked like younger, more masculine versions of him. And one was of his friend Greta Garbo, the (mostly) lesbian film star he asked to marry him – who looked like a more feminine, more glamorous version of himself. Photography really was his lifelong vocation and companion.

The 19th-century French writer Stendhal considered beauty to be “nothing more than the promise of happiness”. But our pessimistic dandy guru Baudelaire was perhaps more on point when he wrote: “The study of beauty is a duel in which the artist cries out in terror before being defeated.”

This is the price of being interesting. I wonder how many young people today are willing to pay it.

“I EXPOSED THOUSANDS OF ROLLS OF FILMS, WROTE HUNDREDS OF THOUSANDS OF WORDS, IN A FUTILE ATTEMPT TO PRESERVE THE FLEETING MOMENT… I STARTED OUT WITH VERY LITTLE TALENT, BUT I WAS SO TORMENTED WITH AMBITION. ONCE YOU’VE STARTED FOR THE END OF THE RAINBOW, YOU CAN’T VERY WELL TURN BACK” – CECIL BEATON

Special thanks to Emma Nichols at Sotheby’s. Cecil Beaton’s Bright Young Things was set to be display at the National Portrait Gallery, London, until 7 June, 2020. However, due to Covid-19, the gallery is currently closed. However, Their website provides a comprehensive archive of Beaton’s work.

The Summer/Autumn 2020 ‘High Art Pop Culture’ issue of Another Man is now on sale internationally. Head here to buy a copy.