Don McCullin on the Stories Behind His Most Personally Significant Pictures

- TextJo-Ann Furniss

“It’s quite emotional to talk about, and I don’t particularly like it overflowing when I talk to people,” the legendary photographer says. “But if I wasn’t emotional I wouldn’t capture the honesty in my images”

This article is taken from the Summer/Autumn 2020 issue of Another Man:

“I do not want people to walk past one of my pictures without realising. They’re meant to stop you and make you look and make you feel. My background played a major role in my feeling towards the tragedies that I saw, the injustices, the murders, the child starvation and poverty. I was an underprivileged working-class English boy. We had a kitchen table the old lady used to scrub to death, a weeny gas cooker... me and my brother, mother and father slept in the same room. I was soon to lose my father at the age of 13. If you’ve seen your father’s body in the front room with candles burning, it changes you. It changes your journey before it’s even begun in life. So I have a deep emotional connection with myself and others and I start reasoning: Why are these people killing these people? Some people say, ‘It’s not your concern, you’re here to photograph.’ That’s not true. You’re there to be concerned. If you’re not concerned you shouldn’t be there. I always went to these places with a mission to try and show injustice, cruelty, poverty, pain and suffering. I was carrying a huge rucksack of causes which you could say were not my causes but they were the cloak of dignity that I had to work under. If I did not set my own rules, I would have been out of control because war is exciting. If you survive it, that is. If you get hit with a bullet it’s not exciting. If you see blood pouring out of your crotch and your legs holed with shell like happened to me one day when I walked into an ambush on the outskirts of Phnom Penh just before dusk, that’s a day of reckoning and you think, this is not meant to be in the script.”

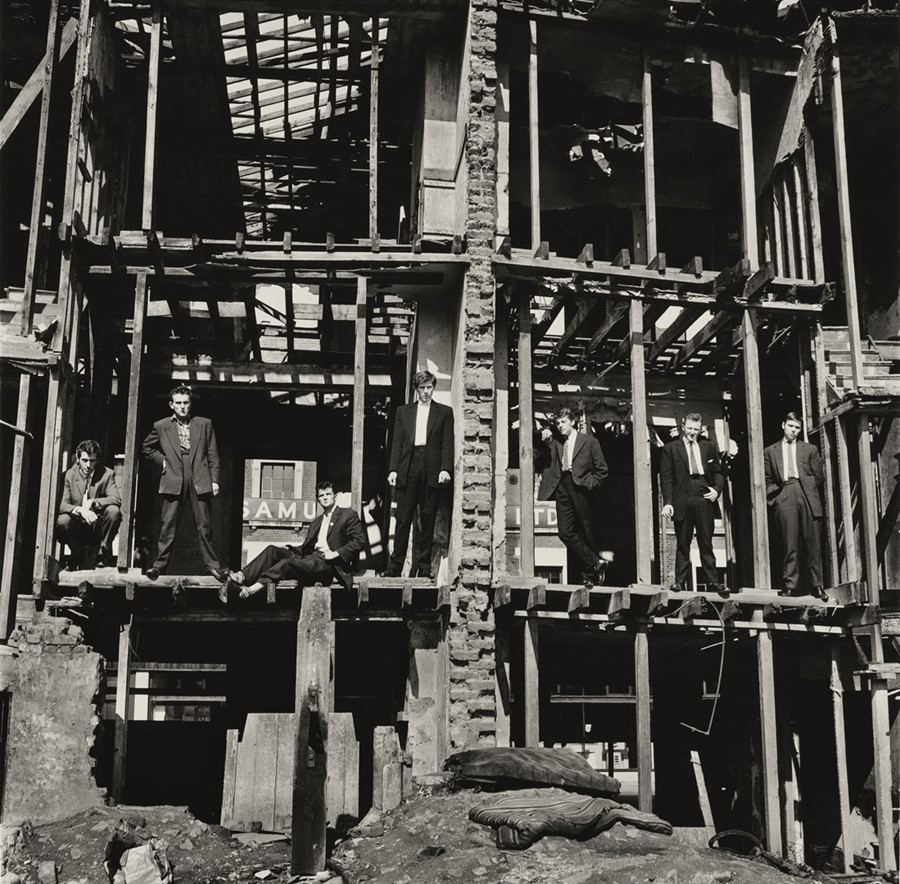

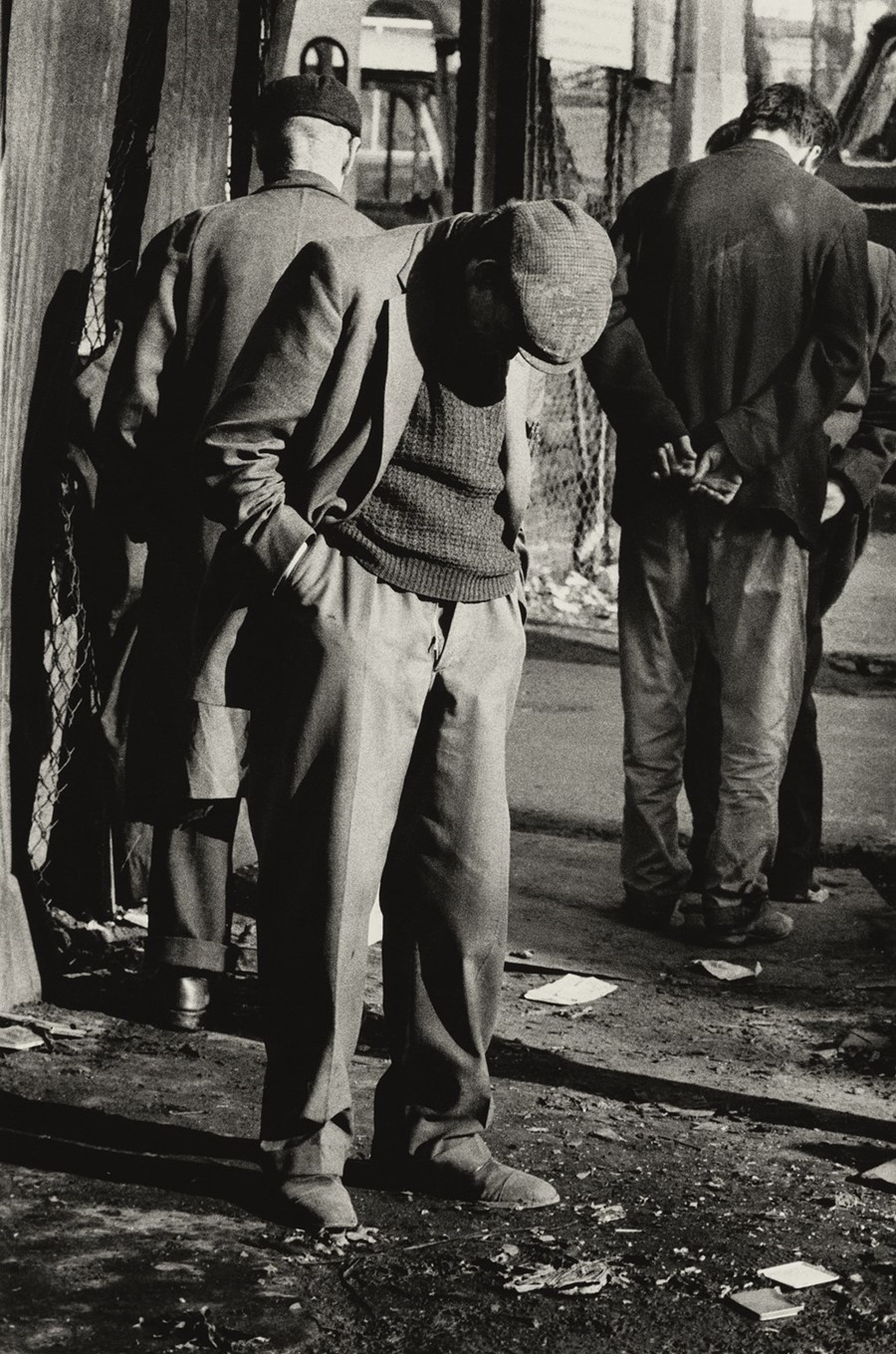

THE GUVNORS – FINSBURY PARK, LONDON, ENGLAND – 1958 (LEAD IMAGE)

“This is the picture that got me started in photography. These were the boys I grew up with in North London, who were involved in a gang clash with another bunch of boys. I wasn’t really a photographer then to be honest, I was floating around and when this picture was published by The Observer in 1958, overnight I was offered every job in England in the media world – people thought I was an established person but I wasn’t. I was about 22 and I had no future. I’d worked in Mayfair in a small darkroom just copying line drawings, and I was doing odd jobs for The Observer – 15 quid for two days a week.”

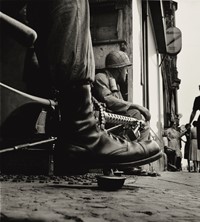

NEAR CHECKPOINT CHARLIE – BERLIN – 1961

“When the Berlin Wall crisis happened I was in Paris with my first wife and I said, ‘When we go back to England would you mind if I went to Berlin?’ I only had one camera, a Rolleicord, it was a square format so it wasn’t a natural reportage camera. I went to Friedrichstrasse in Berlin, and I was embarrassed because I wasn’t a photographer really, but I knew I had a calling for it. I saw this German woman going down the road looking very chic in this dress and I put my camera down and took this picture. I was just leisurely walking around one of the most important news stories in the world because the Russians and the Americans were facing each other at Friedrichstrasse and I was looking into East Berlin and the East German soldiers were coming, armed. So in my naive way I was at the gates of a career, and I didn’t understand where it would take me, but I knew I had a thirst for it. Here we are 60, 70 years later and I think I have a good idea what I was letting myself in for.”

EARLY SHIFT – WEST HARTLEPOOL STEELWORKS, COUNTY DURHAM, ENGLAND – 1963

“These are not straightforward photographs, they’re also taken into the darkroom where I inject into it more of my feeling, more of my sorrows. They’re not glamorous, I’ve deliberately printed them in a way that will show you that these people are not having a great time in the one life they’ve been given. I took this photo in West Hartlepool – I slept in my car all night because when I was young and poor I couldn’t afford hotels. It was one of the coldest winters in England and I woke up in the morning with frozen legs and looked out of my car window and saw this landscape and I thought, ‘This must be Birkenau,’ it seemed as if that was the crematorium of burning bodies. I thought, I need a human being, so I waited and waited, frozen to death, dying for a pee, hungry, dying for a warm drink, and round the corner came this man. It was so early in the morning that I didn’t have much light and so my lens was wide open.

“What makes this picture is this strange fence that has collapsed and gathered frost and it becomes poetry in a way, but it still looks bloody miserable and poor. You don’t want to be that man going to that place every day. I’ve been back since and it’s been completely eradicated. But when you eradicate bad things like that, you also eradicate people’s lives and jobs. The industrial north was the backbone of the so-called British Empire. It was the backbone of the industrial revolution. These are the people who paid the price of filth, dirt, heat, thirst, dangers and god-knows-what terrible accidents and loss of life. The British Empire was created by the energy of the working man in the spine of England, not the people in the south.”

THE CYPRUS CIVIL WAR – LIMASSOL, CYPRUS – 1964

“In 1964 the civil war in Cyprus broke out, when the Greek community were attacking the Turkish villages. I was at The Observer newspaper one morning and the editor said, ‘I’m going to ask you something: would you consider going to the civil war in Cyprus?’ I couldn’t believe what I was hearing, I’m sure I was levitating, and off I went. This was the first day of my real days of war. I went to the city of Limassol, and hired a car and drove through the centre of this Turkish area and there were bullets flying all over me, I was driving the car like a madman. I parked and saw this man coming out of a cinema dressed in this extraordinary raincoat, a very good-looking man in a good-looking raincoat with a very bad English machine gun called the Sten gun, and that was my first picture of war. After he came out of the cinema, women were coming out with mattresses over their heads thinking that would protect them from the bullets, men were running out with babies, and it was an emotional shock to see these human beings running for their lives under a hail of bullets. I had to pinch myself – ‘Am I watching a film? Is it real?’”

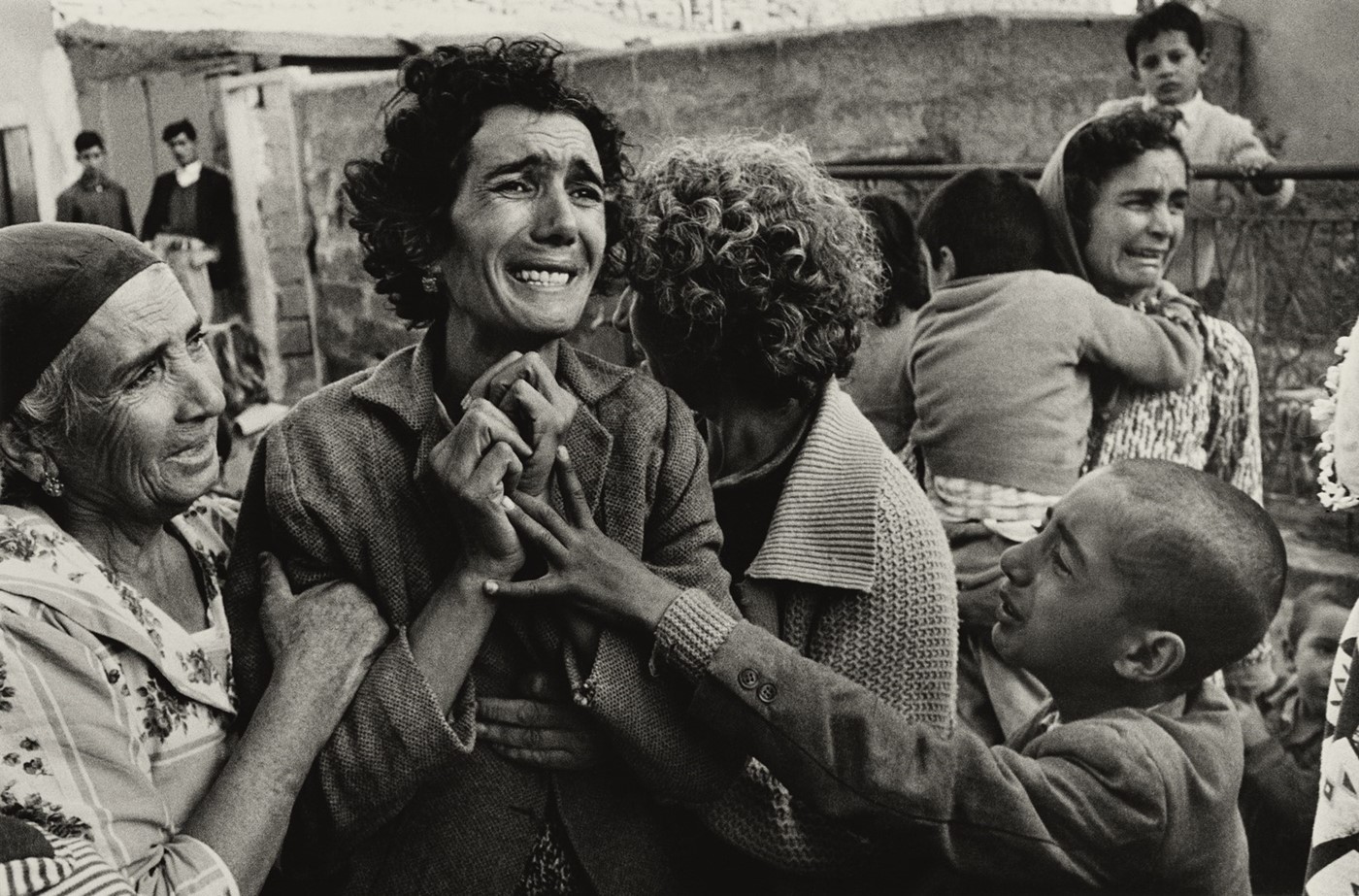

THE MURDER OF A TURKISH SHEPHERD – CYPRUS – 1964

“A few days later I went to a village that had been attacked by the Greeks. We were finding dead bodies under the orange trees in the early morning, covered in dew. This woman had just been told her husband was one of those people found in the orange grove and that’s her son reaching out for her. So this is the beginning of my journey to war and the terrible thing was, I was excited about it.”

SHELL SHOCKED MARINE – HUE, VIETNAM – 1968

“I covered quite a few wars and I wound up in the biggest war of all, the Vietnam war. This picture is of a man who has lost his will to see it through, and the soldiers around him despised him. I saw him sitting there and asked the Sergeant, ‘What’s the matter with that guy over there?’ He said ‘I don’t know and I don’t care.’ American marines are meant to be the most macho men in the world so when a man throws in the towel he’s sort of hated. People called this picture iconic, but when you call something iconic it creeps dangerously close to the artworld. It’s purely photography and it’s purely my eyes and my imagery. But don’t think for a second that I’m not artful. I’m as artful as a cartload of monkeys. But I’m artful because I’m twitchy and switched on, I’m very predatory. I have to be quick and be there and get it.”

GRENADE THROWER – HUE, VIETNAM – 1968

“War photographs like this are almost meaningless because they don’t show the negativity of war, they tend to glamorise courage, bravery and soldiery. All I was doing in this picture was to show the courage of this man who was black – and towards the end of the war in Vietnam it was only the black guys who were getting drafted, as if they were almost expendable.”

RUNNING SOLDIERS – LONDONDERRY, NORTHERN IRELAND – 1971; CHRISTIAN YOUTH CELEBRATING THE DEATH OF A YOUNG PALESTINIAN GIRL – BEIRUT – 1976

“These are street pictures. They’re not battlefields in the sense of Vietnam, but they are streets where people live and they die, as was the case in Northern Ireland, and this one in Beirut. These Christian Phalange people were dragging all the Palestinians out and shooting them dead in front of me, mowing them down and they were crying and pleading for their lives. They shot this young Palestinian girl, and this man with a stolen lute is serenading and celebrating her death on a cold, wild, miserable rainy day. I watched one of the gunmen kill two men in a doorway. Their wives and children were coming down the stairs and the gunmen blew these men to pieces in front of me, brains all up the wall and they were sliding down the wall trying to say something with half their heads missing. This Christian Phalange came to me and said, ‘If I see you taking any more pictures, I’m going to kill you.’ I thought, you know what, I believe you will. He said, ‘Now go, leave this place.’ As I was leaving, and I was quite shaky, I could hear music. I was with a reporter from The Sunday Times and we looked down the street and saw these guys. I said, ‘Martin, I’ve got to take this picture.’ He said, ‘You know what the guy just said,’ – but I could not walk past this picture. I took it and we got to the checkpoint into the west part of Beirut on the Arab side, and they asked for our passes, and I gave him the Christian Phalange pass. We were dragged out of the car and they said, ‘We’re going to cut your throats’ – they were swearing and shouting. An hour later a man came into the room where we were held and by then my mouth was completely locked as if someone had put superglue in it, I was so dehydrated and afraid. This man came in with a cigarette like in a French movie – he had a leather jacket and a polo neck sweater and he said: ‘You’ve been very foolish, these people want to kill you, but I know you are genuine newspapermen. I’ve explained to them it was just a mistake. Would you like a cup of coffee?’ I’ve never walked away with more shaky legs because I thought I was a goner. You don’t sign up for this as a photographer. You think you’re just going to press that button, but it’s not that easy. Photography is like climbing Everest without oxygen and the weight you’re carrying is a moral, mental weight that is twice as heavy as any other person is expected to carry in his life. You go out into this photographic world thinking, ‘God, I’m having such an exciting, wonderful life,’ but if you think it’s free of charge, it’s not. It’s loaded with penalty.”

HOMELESS MEN SLEEPING WHILE STANDING – WHITECHAPEL, LONDON, ENGLAND – 1970

“This was taken in Spitalfields, near the Hawksmoor church. These men were like horses – if you’re standing and you nod off a bit, you suddenly jerk because you think you’re going to fall over. So every two or three minutes these men would suddenly jerk like that and then look at you with guilt. I wouldn’t call them a family, but they were a community that became a family, a family of lost men, lost souls.”

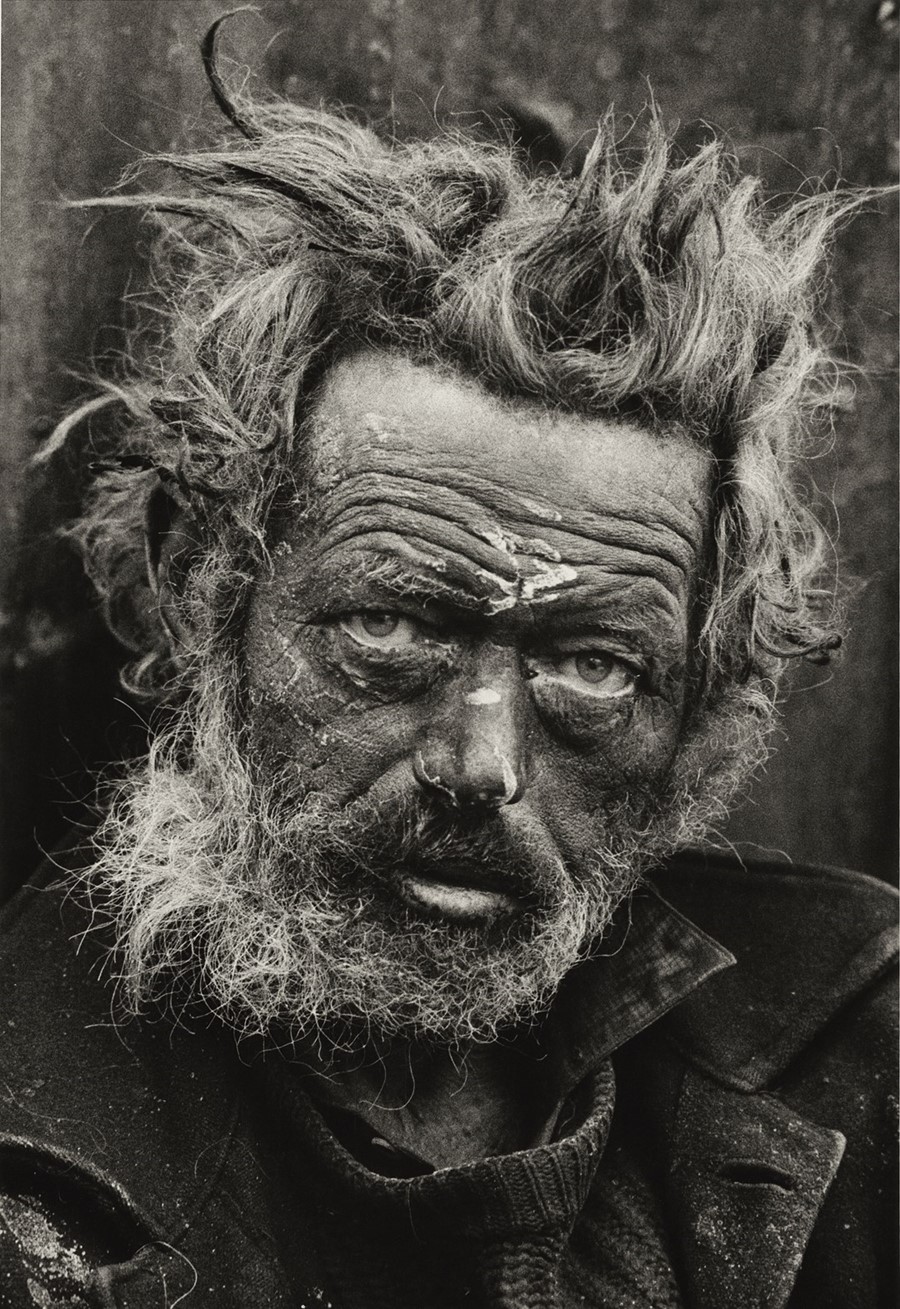

NEPTUNE – SPITALFIELDS, LONDON, ENGLAND – 1970

“When I did this story about the homeless in England, I thought I came close to doing my best photographic work, and it was in my own country. It wasn’t a war as we know war, but it was another kind of war, a war of mentality, a war where men lost their dignity, lost their homes, lost their families. In those days they were called down-and-outs and they were often associated with drink, which wasn’t totally fair because this man here had been cast out of a mental institution. These men were totally wrongly labelled as drunks, losers, bums, nobodies. They were human beings. This story was all taking place east of Aldgate – around Liverpool Street station, around the great wealth of the City. You had this extreme tragedy in a place where all the money was being generated in England. So the contrast was challengingly striking, people who were going into the City to make millions passing people like this in shop doorways.”

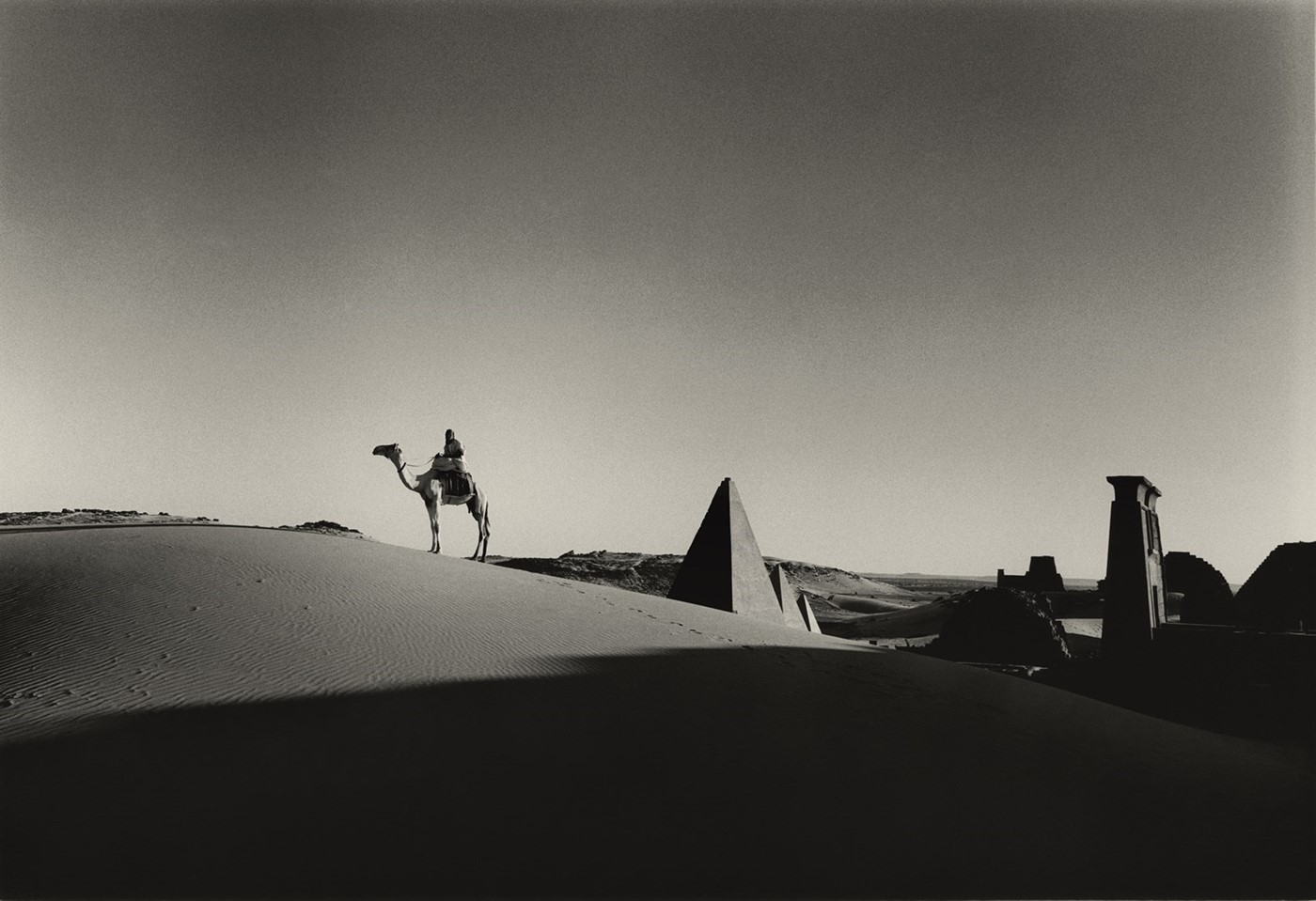

MEROË, THE EAST BANK OF THE NILE, SUDAN – 2012

“This is a place called Meroë on the sixth cataract of the Nile, where there are 50 miniature pyramids and tombs. This is in a book I did called Southern Frontiers. I’ve been playing with history, social events, social tragedies, war... in a way it’s almost a full circle of human existence with its stresses and problems and its histories and its architecture. Photography has brought me an education that several universities couldn’t give me. I’ve had such a great life, there wouldn’t be enough money in the world to pay for all the things I’ve done and the places I’ve been and the things I’ve learned. I’m still learning. Every day teaches me something new. I’m searching before I become parchment dust, I’m searching for surprise and joy in discovery. But you know what they say about curiosity. And sadly it killed many of my cat friends.”

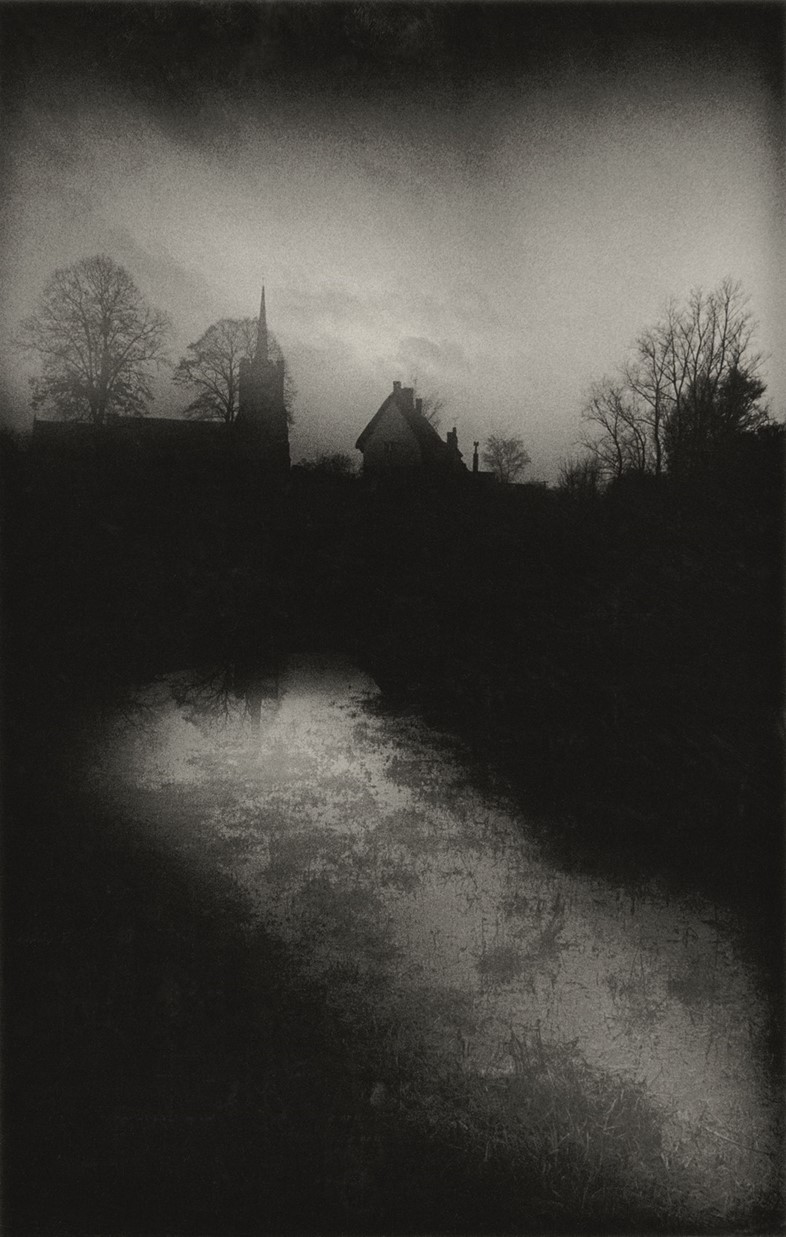

DUSK – HERTFORDSHIRE, ENGLAND – 1973; DEW-POND BY IRON AGE HILL FORT – SOMERSET, ENGLAND – 1988

“What I’m trying to do with these, is cancel out the others. This is in a small village in Hertfordshire at dusk. When my first wife was alive we lived in this village. The other is in Somerset, a dew-pond with an Iron Age fort over the back. I came to Somerset as a child at the age of five, because I was evacuated during the Blitz. Years later I walked into the house I live in now in Somerset on a cloudless May day, and I said to the woman I was with, ‘I’m going to buy this house.’ She told me not to be too hasty. But I heard water and ran down the valley and saw a huge trout in the stream, and I said: ‘I’m buying this bloody house!’ It was the smartest move I ever made because it all came together then. It has been my spiritual home, my sanctuary. It’s as if I was born here. I went through some personal turmoil and I was in such pain. I came here and got pissed every night, I’d drink Special Brew to keep me going, then I’d hit the wine and crawl upstairs totally pissed out of my brains. I’d broken my arm in a gun battle in El Salvador – fell off a roof in a gun battle like in a Hollywood film. They were firing at rebels in one of the Spanish churches and the roof collapsed. I fell backwards and broke all my ribs and shattered my arm. So I was dragging myself around here with this broken arm, crying and drinking and punching doors. Because if you are emotionally charged and all this work is in you... I was poisoned. I’d poisoned myself, I was poisoned by the work and at the end of the day I landed like a lead balloon on my head. And then I got over it. I started photographing the landscape in the early 90s. The landscape became my shrink, and it cured me.”

Don McCullin is on display at Tate Liverpool from June 5, 2020, however booking is not available for this exhibition due to the disruption caused by coronavirus.