James Greig explores the Hayward Gallery’s new exhibition Among the Trees and our shifting relationship with forests

- TextJames Greig

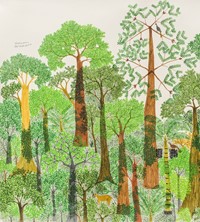

Among the Trees, a new exhibition at the Hayward Gallery, looks at how artists have depicted trees and forests over the last 60 years – a period of time which roughly coincides with the span of the environmentalist movement. As well as having an ecological focus, the exhibition explores some age-old themes of what forests mean to humans; the ways they both scare and seduce us.

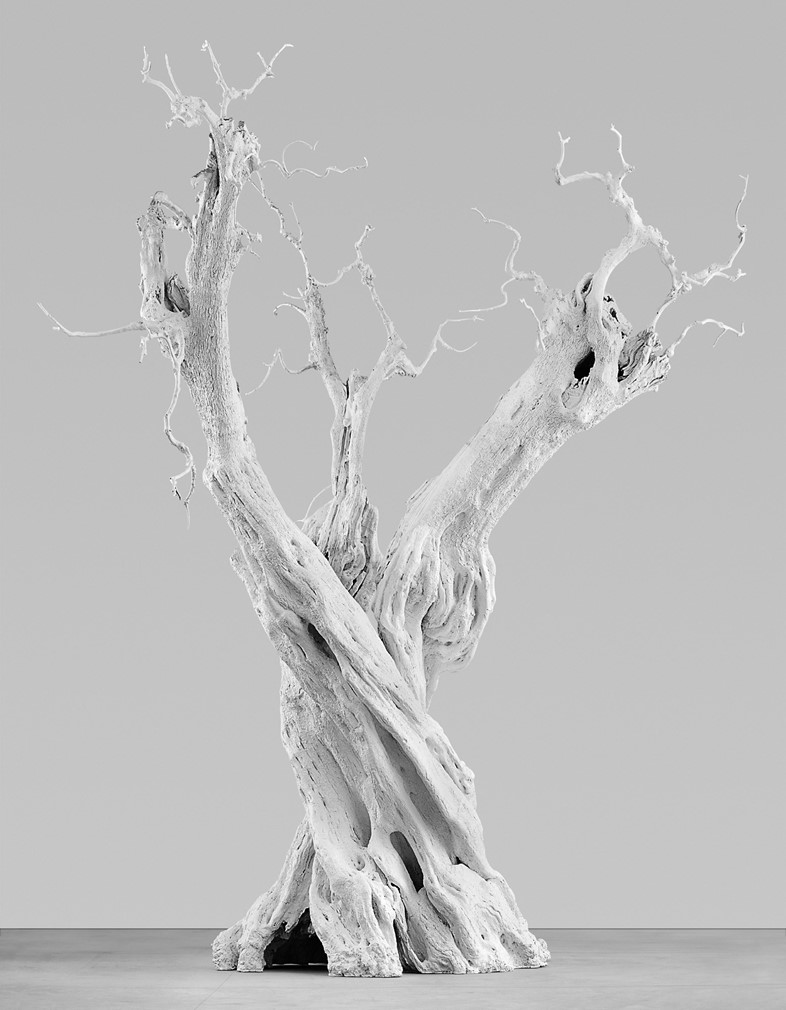

The exhibition is timely: all over the world, from the Amazon to Australia, forests are burning. In 2019 alone, there were 4.5 million forest fires, 400,000 more than 2018 – and this trend looks only set to rise. Understandably, given the bleak prospects for the world’s trees, a feeling of ecological anxiety pervades Among the Trees. Roxy Paine’s installation Desolation Row shows a charred forest with smouldering embers, a landscape in the wake of a terrible, all-consuming fire. It really is quite sobering to witness. Mariele Neudecker’s And Then the World Changed Colour: Breathing Yellow, meanwhile, encloses a woodland scene within a tank and colours it with a sickly, polluted yellow. Forests have often been depicted as threatening to humans; in these works, this dynamic reversed, and it is humans who pose the threat.

According to Ralph Rugoff, the exhibition’s curator, “We have a sense that the world’s forests are under threat. There’s images which are hopefully making people think about trees and the value we put on them, and because of global warming and the relationship which trees can play in terms of cleaning carbon dioxide out of the air. We’ve also seen that trees are crucial to our survival and having a livable planet.”

Perhaps owing to the ecological factors outlined above, the cultural moment we’re living through means we are more fascinated with forests than ever. Forest bathing, an old Japanese tradition which consists of ‘bathing’ in woodland air, is becoming popular in the UK. This can be viewed as part of a broader cultural landscape which lionises the natural, which has seen an explosion in brands like Patagonia bringing outdoor wear into Europe’s city centres. The idea is that spending time in the forest is restful, that it acts as a counter to the superficial hustle and bustle of the modern world. But this sense of the forest as a restorative place is not particularly apparent during the exhibition, although Luisa Lambri’s light-suffused photographs of captured through glass do suggest something holistic and healing.

Luke Turner, author of Out of the Woods, a memoir and nature book about London’s Epping Forest, is sceptical of the idea that being in a forest automatically confers healing benefits. “This idea really makes this massive separation between people and nature. It’s a way of avoiding seeing humanity as part of the ecosystem and as a destructive force within that ecosystem which needs to reconsider how it behaves. But we are part of nature. There’s a lot of separation of ourselves from forest and woodlands. We think of them as healing places but it’s quite simplistic to think that if we go into them they’ll cure all our ills.”

If you described the concept of forest bathing to someone from basically any point in the UK’s history, they would probably find the idea quite baffling. Trees have always been portrayed as frightening places (think Macbeth, a huge portion of European fairytales, The Blair Witch Project, Deliverance, Harry Potter … the list goes on). There are evolutionary and historic reasons for this, which differ from culture to culture. “I think we have a species-wide memory which is very fearful of forests,” says Turner. “Forests were useless, you couldn’t get through quickly, you were prey to other things. Humans very quickly were more into open woodland landscapes. In the UK, a lot of our ideas of civilisation come from the Romans and they hated the forest, because that’s where the Germanic tribes would come out and attack them, who they never managed to defeat.” This sense of sinisterness is apparent in parts of the exhibition; such as Gillian Carnegie’s black, entirely monochromatic painting of tree stumps, Black Square, which emanates a certain level of evil. Giuseppe Penone’s macabre sculpture Continuerà a crescere tranne che in quel punto … depicts a severed hand gripping a tree trunk, looking like the remnants of some unspeakable ritual. Thomas Struth’s photograph paradise 14, Yakushima is, as its name suggests, far less grotesque, depicting a dense, fertile and rich woodland scene. But it still carries a trace of fairytale menace, the feeling that forests are extremely alive and yet full of dead things.

This sense of forests as evil places is as culturally relevant now as it ever was. For example, two of the most critically acclaimed horror films of the last decade, Ari Aster’s Midsommar and Robert Eggers’ The Witch are set in or near woodlands, something which is far from incidental in their visual language. Midsommar, basically the forest bathing session from hell, turns the contemporary idea that forests are restorative entirely on its head. Unlike most horror films, it’s drenched in sunlight, but the trees form a constant, unsettling backdrop (in one blink-and-you’ll-miss-it shot, the face of the protagonist’s dead sister appears superimposed onto the forest). The film is about a murderous, secluded cult which is separated from the outside world by trees. The forest is portrayed a place of evil and also a place of wildness, where the laws don’t apply and traditional authority is out of reach, which is part of a lineage stretching back to Shakespeare. Similarly, arthouse horror film The Witch, about a family of 17th-century Puritans plagued by satanic forces, positions forests as places of evil, but also temptation. What goes on among the trees might be sinister, but it’s certainly a lot less boring than hanging out with your fundamentalist Christian family. Forests are places of witchcraft, paganism, midnight rites; things which are evil but, crucially, kind of fun.

This sense of forests as being places of decadence and excess is long-established. In Shakespeare’s work, forests are sometimes (but not always) stage-sets for romance, love, transformation, and wild encounters. “If you look at Shakespeare,” says Turner, “forests are where all the fucking happened, where society was turned on its head. Even today, people go into the forest to be decadent, to do things they shouldn’t, to get in touch with a truer self, to come and explore difficult things within their lives. That’s historically what forests have always been.” Forests have always been cruising grounds, for instance, and drinking spots for rural teenagers (incidentally, one of my highlights of the exhibition was Turner Prize nominee’s George Shaw’s paintings of banal, suburban wilderness, the kind of hinterlands where young people go to get away from the laws of adults). Perhaps the problem with forest bathing is that it’s too pious to be truly in keeping with the Dionysian spirit which the forest embodies, at least in British cultural history. Rather than spending £25 on a forest-bathing session, you might have a more genuinely epiphanic experience drinking a two-litre bottle of Strongbow and getting off with a stranger in some shrubbery. It’s what Shakespeare would have wanted.

This exhibition does an excellent job of showing that we need forests, whether for ecological reasons of straight-up survival or something more nebulous and profound. In an era in which everything feels very surveilled and regulated, it’s important that we still have these mysterious, eerie places. It’s that sinister quality which makes them so enticing. It will be a sad day if forests ever stop being frightening.