Miss Rosen tells the story of George Platt Lynes, whose secret photographs were saved from destruction by the Kinsey Institute

- TextMiss Rosen

Tales from another time ... In a new series, titled Illicit Histories, Miss Rosen tells the stories of queer art’s pioneers, unpacking the lives and work of people who revolutionised gay erotic imagery – often in defiance of censorship laws.

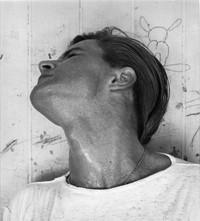

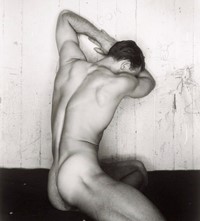

While making his name as one of America’s foremost fashion photographers of the 1930s and 40s, George Platt Lynes (1907–1955) spent years working in secret on a series of male nudes that were revealed in the years after his death. The photographs only survived by the fortunes of fate; Lynes, who famously led an extravagant life, became pressed for money and sold more than 600 prints and several hundred original negatives to Dr Alfred Kinsey’s Institute for Research in Sex, Gender, and Reproduction. The rest where destroyed by Lynes himself, just prior to his death.

Although Lynes rarely photographed explicit acts, he took care to create images that, as he told Kinsey in a letter, rendered the word “erotic” inadequate. Kinsey, for his part, did not look at the work as art but as artefact: evidence of sexual behaviour and fantasy in postwar America. Lynes, on the other hand, recognised the work as the most important in his highly successful commercial and fine art career, a career that started by pure serendipity.

Born in East Orange, New Jersey, Lynes led a charmed life, attending the Berkshire School in Massachusetts where he met lifelong friend Lincoln Kirstein. Before attending Yale, his parents sent him to Paris in 1925, where he quickly fell in with cafe society, spending time with Gertrude Stein, Jean Cocteau, Marc Chagall, writer Glenn Wescott and curator Monroe Wheeler (with the last two men he would have a triangular love affair for more than a decade).

In Paris, he began taking photographs, as an amateur might: with no intention other than recording the moment for himself. Upon his return to the United States, Lynes dropped out of Yale and opened a bookstore in Englewood, New Jersey in 1927 and continued his habit of photographing his famous friends, displaying the photographs in the store to give it an air of panache.

An integral figure in various New York circles, Lynes traded bon mots with Dorothy Parker, Paul Cadmus, George Tooker, and Julien Levy, an art dealer and critic who exhibited Lynes’ photos in his New York gallery in 1932. That same year, he also exhibited his work in Murals by American Painters and Photographers at the Museum of Modern Art.

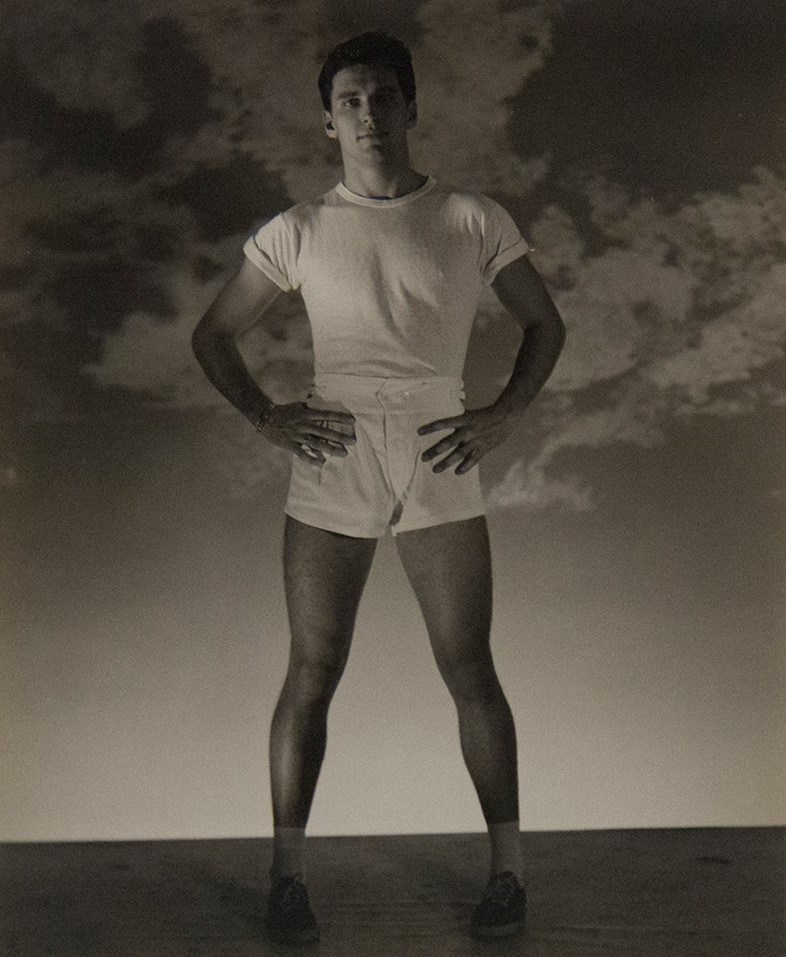

With early success secured, Lynes opened a studio and set to work, shooting portraits for high-society figures, commissions from Harper’s Bazaar, Town & Country and Vogue, for which he photographed a cover of celebrated model Lisa Fonssagrives, and the principal dancers of George Balanchine and Lincoln Kirstein’s newly founded company, today known as the New York City Ballet.

While Lynes’ sexuality was an open secret, few knew he was working on a series of male nudes, which began with the Mythology series in the 1930s. These works reveal the influence of the artist’s exchanges with Surrealists like Salvador Dalí, embracing the movement’s distinctive blend of dream-like theatricality and classical forms. By incorporating elements of Surrealism to his pictures, Lynes aspired to elevate his photographs to the canon alongside masters from ancient times and the Renaissance – when the male nude was revered, rather than reviled, by the powers that be.

“Lynes was handsome, charismatic and had very good taste,” says gallerist Brian Paul Clamp. “He was also said to be very in control in the studio: decisive, opinionated but efficient and able to make things happen. He was known for distinctive lighting and wonderful use of props. With his lighting, he could style the photographs to make the clothing feel contemporary and showed things off in their best light.”

After completing his work on the Mythology series, Lynes continued making nudes sans themes. They were a necessary part of his artistic process, though he was forced to keep them hidden from view – despite the accolades all his other work received. “To exhibit and sell the homoerotic work would have taken it a step too far,” Clamp says. “That would have been an insult to his commercial clients and the magazines. He never wanted to do that because he didn’t want to jeopardise his income even though he felt the male nude work was his strongest work.”

Instead, the male nudes were circulated privately, “literally kept in closets over the decades,” Clamp reveals. When Lynes learned he had lung cancer just months before his untimely death at the age of 48, he destroyed his archive – perhaps concerned about allowing anyone to be exposed and persecuted in Red Scare America.

Though his work was both known and discussed in the decades following his death, it wasn’t until the 1981 publication of the seminal monograph George Platt Lynes Photographs 1931–1955 (Twelvetrees Press) that the full scope of his oeuvre came into view and his legacy was recognised in full. With the integration of his male nudes into his larger body of work, a new generation of artists – including Robert Mapplethorpe and Herb Ritts – recognised Lynes as a pioneer and a guiding light.