Annie Leibovitz called him “the rock ‘n’ roll photographer” – then he all but disappeared. A new film and book uncover the tale of abuse and redemption behind the photographs which defined an era

- TextMiss Rosen

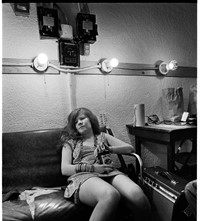

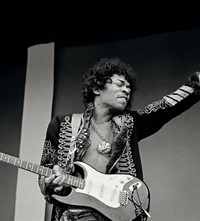

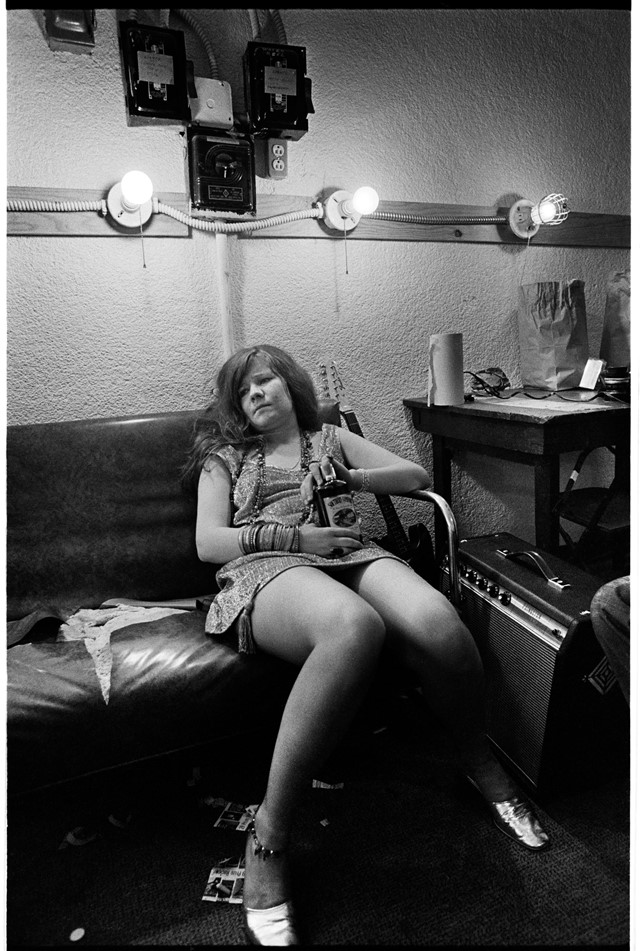

In March 1984, Michelle Margetts, a 20-year-old journalism student at San Francisco State University, met Jim Marshall (1936-2010) at a bar in downtown San Francisco, to interview him for a ‘Where Are They Now?’ assignment. Marshall, who had famously shot Johnny Cash flipping the bird during his historic 1969 performance at San Quentin State Prison and Jimi Hendrix burning his guitar at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival, was, in the words of Annie Leibovitz, “the rock ‘n’ roll photographer”.

But Marshall, then 48, was down on his luck after being arrested on a gun bust in 1983 and doing work release to avoid prison time. “When I met him I found him hideous: a malevolent gnome,” Margetts recalls of the man who would become a short-term boyfriend and lifelong friend. Given the opportunity to talk, Marshall poured out his heart, revealing the deep vulnerabilities that lay beneath his gruff exterior. Then, just before it was to be published, Marshall sabotaged the entire thing and the story disappeared.

Fast forward to last year, Marshall was dead and buried, and Margetts was preparing to be interviewed about his life for the 2019 documentary film, Show Me The Picture: The Story of Jim Marshall. Just hours before the film crew arrived, she heard a voice in her head urging her to open a box Marshall sent decades earlier. “At the bottom, there was a manila folder. On cover of it, Jim wrote in black Sharpie: ‘Reams of Bullshit about Jim Marshall.’ I realised it was the background information he gave me the second day I interviewed him. Then I saw the original article. I literally stopped breathing.”

When the film crew arrived, Margetts mentioned the discovery in passing and initially resisted the idea of sharing it – only to end up reading the entire story aloud on camera. “What you see is me reading it for the first time in 30 years! I was hanging on my couch for my dear life,” she says. When she finished, the entire room was in tears. Margetts had captured the truth about who Jim Marshall was: a man of conflict and contradiction, haunted by demons. The reading became the backbone of the film, revealing Marshall’s profound emotional needs which propelled him as both artist and man.

“Jim was complex,” says Amelia Davis, Marshall’s longtime assistant, executive producer of the film, and author of Jim Marshall: Show Me the Picture (Chronicle). “To understand his work, you have to understand all of him because all the things he did are the reasons he got the photos he did and I don’t want to hide it. Jim may have regretted some of the things he did but he was never ashamed of his life.”

Born in Chicago, Marshall’s family moved to San Francisco when he was a year old; soon thereafter his father left, an void he’d feel for his entire life. A child of immigrants, Marshall always identified with the underdog and championed the revolutionary spirit of jazz, the Beats, and the hippie scene – all of which converged in San Francisco during the 1950s and 60s. To tell Marshall’s story in 360 degrees, the film brilliantly weaves his photographs with historic footage, music, and interviews with friends including musicians Peter Frampton and Graham Nash, actor Michael Douglas, photographers Bruce Talamon and Anton Corbijn, as well as Marshall himself.

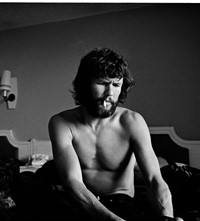

Show Me the Picture is an unvarnished portrait of the artist as a drug addict and weapons fetishist who adopted a tough-guy posture to mask his deep sensitivity and pain, an intricate albeit volatile cocktail that allowed him to get close to his subjects in the way few others ever could.

“I’ve always liked cars, guns, and cameras,” Marshall says in the film. “Cars and guns have got me into trouble. Cameras haven’t.” Marshall bought his first camera, a Leica, in 1959, and went into North Beach and the Filmore district, where he taught himself everything he needed to know, and quickly gained the trust of luminaries like John Coltrane and Miles Davis. He spent time with the Freedom Riders and attended the March on Washington, as well as Woodstock and Altamont, where he lost 18 rolls of film while trying to escape the chaos. For all of his provocations, Marshall’s subjects implicitly trusted him because when he had a camera in his hand, he was the consummate professional.

But, as the film makes clear, the real story of Marshall’s life happened when he put the camera down. Amelia Davis remembering first meeting Marshall at a party in 1997, shortly after her mother had died and she had been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. “I was very vulnerable, sad, and angry and I think Jim was at a similar part in his life and it worked. We became family,” she says.

“When he would yell or scream I would yell back at him. He respected that I stood up to him. Most people would run away crying and never come back. I can’t explain why I kept coming back other than I saw the importance of his photography. His photos were his children, which he protected and cared for when he was alive. He said, ‘The only person I trust to take care of my children when I am gone is you.’”

Marshall, who often went on coke binges in his studio, openly spoke of his impending death. “He always said, ‘When I die, I don’t want you to find me because I don’t that want to be the last image in your head of me’,” Davis remembers. “He also said, ‘I want to die in my sleep and go very fast.’ He got his wish.”

In 2010, Marshall was found unconscious lying in bed with a book on his chest at the W Hotel in New York and was pronounced dead at the scene soon after. It was a peaceful ending for a man trapped in the vicious cycle of abuse and redemption.

Show Me the Picture is as a rollercoaster of emotion just like Marshall himself. “He could be fucked up out of his mind and the next moment he is this incredibly sweet, thoughtful person,” Davis says. “That was Jim. I wanted everyone to experience that in the film.”

Show Me The Picture: The Story of Jim Marshall will have its New York premiere at the Cinépolis Chelsea on November 12, 2019. The film is released in the UK by Modern Films on 31 January 2020.

Jim Marshall: Show Me the Picture by Amelia Davis, published by Chronicle Books 2019, is available now.

Two exhibitions of Jim Marshall's photographs go on show at the Rebecca Hossack Gallery (January 6–24 2020) and the Royal Albert Hall (January 28–March 3 2020).