Unpacking the monsters of the Swiss painter who inspired Ridley Scott’s Alien – which celebrates its 40th anniversary today

- TextFinn Blythe

“Hans Ruedi’s dreams were absolutely crucial to his work,” says Carmen Giger, the Director of the Giger Museum in Switzerland and HR Giger’s second wife. “He said if he hadn’t had the opportunity to paint, he would have been a special case for psychiatrists.”

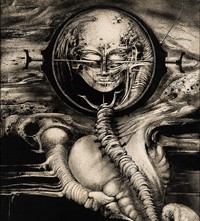

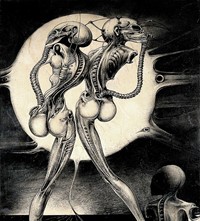

Born from the horrors of two world wars, childhood trauma and a heightened receptiveness to his own subconscious, the age-defying terror of HR Giger’s Alien – the monster he created for Ridley Scott’s 1979 film of the same name – is a sublimation of collective human fears. 40 years on from Alien’s release, it was Giger’s contribution, and the way it mined the darkest recesses of the psyche, which prompted Scott to recently concede that his “great monster” made Alien “a C film elevated to an A film”. The monster movie that had previously played out in derelict houses or open water – as was the case for Steven Spielberg’s 1975 Jaws – now took place in the infinite void of space, and its Xenomorph antagonist – far removed from werewolves, sharks and other terrestrial beasts – was an otherworldly incarnation of evil, fit for a world of unprecedented destruction.

Giger’s Academy Award-winning contribution to the film, as with all his work, was a means of remedy. The nightmares that never left him, the images that became imprinted on his mind and his anxieties for the future were confronted and channelled through his airbrush. The honesty with which he translated what he saw allows viewers even now to confront a darkness they would otherwise suppress. Below, Carmen Giger discusses the inimitable imagination of her late husband and the visions that remained forever a part of him.

Ancient Egyptian symbolism

“At the age of five, his sister, who was seven years older, brought Hans to an exhibit about ancient Egypt at a local museum. Down in the cellar was the mummy of an Egyptian princess, with blackened bones still covered in patches of skin. His sister laughed at him because he was so frightened but he told me that he went there almost every Sunday after that, alone, to sit with the mummy. That experience accompanied him all his life, and those themes: the black abyss of the cellar, the bones and Egyptian culture influenced his work massively. If you look at the monster from Alien, it’s not only black, with bones protruding from under the helmet, but it has this elongated head that you see throughout Egyptian culture.”

The spirit of the age

“Hans grew up in the Second World War and lived in Chur but spent a lot of time in Flims, a ski region about half an hour away. His mother was always afraid there’d be bombing so they’d spend a lot of time up there, including while she was pregnant with him. I really think that the fears of a mother can be transmitted to the child while pregnant.

“As a child, when you don’t have much of a filter anyway, Hans Ruedi’s antenna were bigger and more fine-tuned. He never had a strong sense of filter or boundaries so these fears just passed through him. He was very open to the unconscious and receptive to all these societal fears, like painting small creatures that had barely survived an atomic war [Atomic Children, 1967], and viruses – everything you can’t grasp – he was afraid there would be a chemical war. The more he painted and did his inner work with it, the more he mastered those fears, but definitely his art was born through an anxiety and openness to fears that many people have but suppress. He was just more open to the unconscious and through his talent was able to paint it. That was his medicine.”

Freud and his traumatic birth

“He read Freud and Jung and was extremely interested in them. Let’s say we have different levels of the unconscious, Jung added deeper unconscious levels with the collective unconscious which is deeper than the personal unconscious. In the collective unconscious you can find all these heavy impulses like warfare and sex, which are totally uncontrolled.

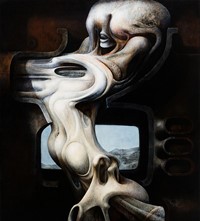

“He always said he had a really difficult birth, that he had to be pulled out using forceps and that he could remember it. It started with these dreams of a huge room with just one opening. He’d panic and want to escape through this small tunnel that got continuously tighter but this paperclip-like object blocked his exit and he couldn’t get back to the room because his arms were tied. Around 65, these things came up again and I could feel that panic in him. We had a psychiatrist friend, Dr Stanislav Grof, who often talked with Hans and was very much interested in the Birth Trauma because he claimed it was comparable to encountering one’s psyche. In Giger’s case, his difficult birth was always in him. Through painting passages [Passages I-XI, 1969] he said he could go over a lot of claustrophobic pains and panicked feelings he still had.”

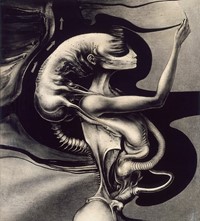

The women in his life

“He really adored his mother but his father, a bright and well-respected pharmacist, was not very accessible. Having lived through the Second World War, Hans was absolutely confident that it could only have been done by men and his picture of men, therefore, was like the Beast from Beauty and the Beast, which he also encountered as a small child. He was inspired by this photograph of John Marais and Josette Day [from Jean Cocteau’s 1946 version] – not just what she’s wearing, but the decoration on her crown is also repeated in his art.

“His type of anima was more a redemption from the dark male that he identified with. I think it had to do with the picture he had of himself and men compared to these beautiful girls he was surrounded by as a kid. He told me he once used to stand at the window of a girl he adored when he was very young because she was so beautiful. All the boys laughed at him because he just followed the girls and was totally fascinated by them and what he saw as purity.”

Mysticism and the occult

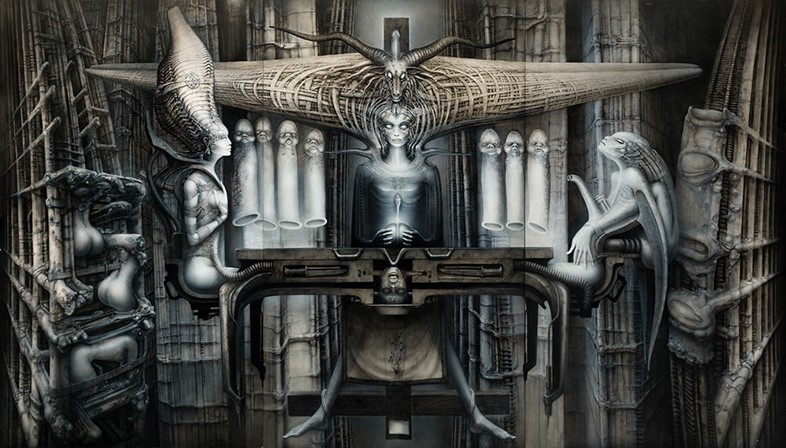

“His fascination with the occult came from Sergius Golowin, a writer and close friend he met just as he was starting work on his Necronomicon book. Golowin knew a lot about the occult and mysticism and introduced Hans to people like HP Lovecraft and FM Murer. The light and dark snakes he used in his Spell paintings for instance, were a mythological reference to the Fall of Adam and Eve. Spell III [1976] symbolises our quest for enlightenment with Baphomet symbolising humanity’s position between the animal kingdom and the divine.

“His interest in the occult is clear because the big topics of the soul are there: sexuality, redemption and power. But he never practised these things, he had a really good centre. He couldn’t watch a documentary of the Second World War where there were real corpses, he couldn’t even eat meat on the bone, yet he painted them all the time. You can see where his fears came from and what he did with them, but he never wanted the hard confrontation, with real war and real death. Even the demons he encountered – and this is where the Alien is so special and even beautiful – he translated into another form, an elegant form, one that people can look at and look into darkness itself, but it’s majestic.”