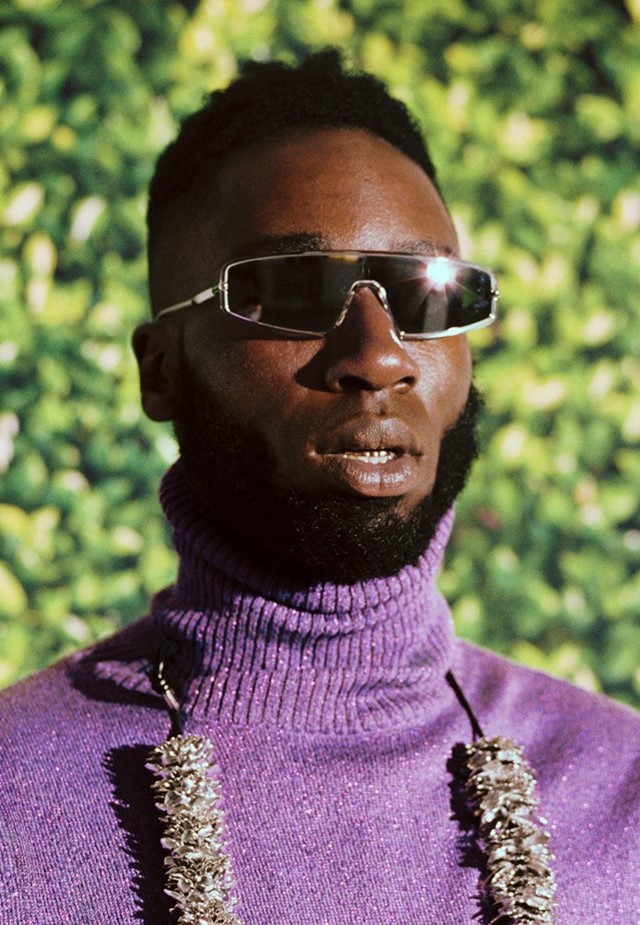

Kojey Radical: The Beautiful Anomaly of British Rap

- TextOtamere Guobadia

‘‘We were asking, ‘How do we exaggerate all this blackness to the max?’”: Multidisciplinary artist Kojey Radical tells Otamere Guobadia about his new project, CASHMERE TEARS

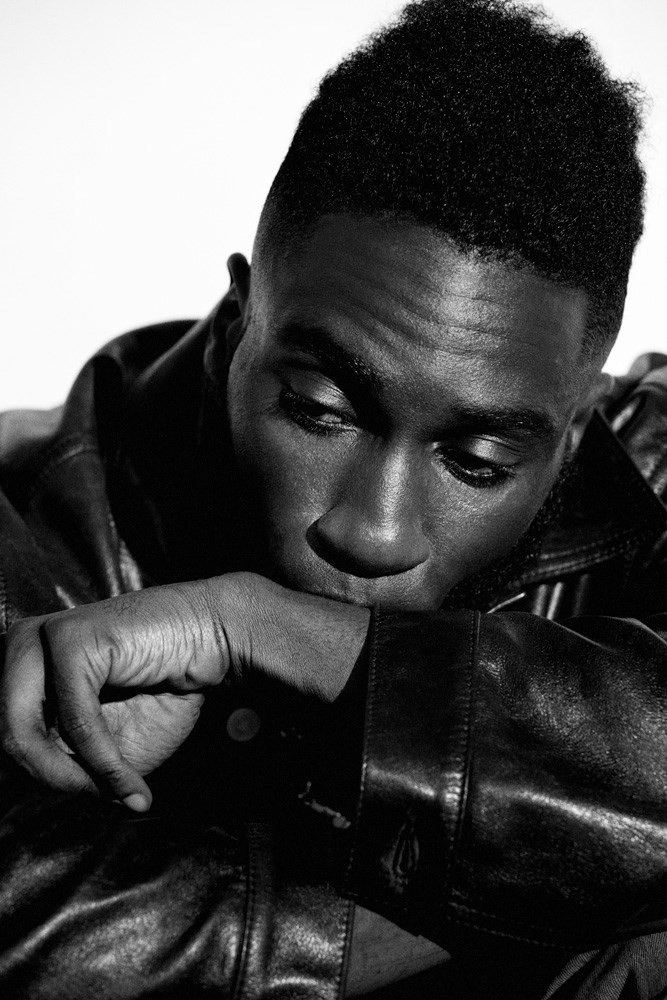

Kojey Radical is something of an anomaly among black British male rappers. When I encounter him in the library at Shoreditch House, he is serving much the same meticulous yet effortless look I first observed him in, outside of a much-delayed Tokyo James show at London Fashion Week – an amalgam of street and dandy which borders on the princely. He reclines in a Patta two-piece paired with Dior Saddle bag, pearl bracelets, a heart-shaped locket and Jil Sander boots; all worn with a casual energy. In both his music and fashion Kojey shrugs off the traditionally austere impositions of hypermasculinity in favour of something nobler and much more interesting.

Indeed, no one could ever accuse Kojey of not using the full potential of his voice; the 26-year-old black British multidisciplinary artist sings, raps, and performs spoken word in his music, but figuratively, he is a man unafraid to immerse himself and his art in sensitive subjects. Be it reflections on the hypervigilance instilled by a world of mass shootings and violence, reflections on faith – or the waning of it – or the allyship of showing the diversity of gender expression and sexuality in his music videos, he shows a keen awareness of his ability as an artist to uplift and meaningfully mould the conversation.

Despite some clear influences and a deployment of forms and styles ranging from gospel and spoken word to grime and hip hop, Kojey’s musical endeavours enjoy a certain liminality, encompassing multiple genres and all the spaces between, without necessarily feeling the need to definitively declare itself any one thing. This is fitting for a man who attempts to constellate his broad talents – illustration, fashion design and, of course, music – in service of a fully realised artistic expression. Ahead of the release of his upcoming musical project, CASHMERE TEARS, Another Man caught up with the artist.

Otamere Guobadia: I like your outfit. You love your fashion don’t you?

KR: We try! Do you know what the thing is, nowadays I’ve got a bit more money, so all the stuff I would have liked to put together back in the day, I can do now.

OG: Who are your great style inspirations?

KR: Jaden Smith. I’d put him first because I’ve not been inspired for a long time, and he was one of those kids that was taking risks that I could appreciate. Like when he wore the skirt, I was like ‘yeah wicked!’ And now he’s like shaving his head on stage, and holding his hair like a fashion accessory. I just like the otherness, not even necessarily everything he wears, just about how willing he is to be the ‘other’. And Yohji Yamamoto, though he only wears black, it’s the commitment, it’s the cut, it’s the silhouette. I think if you can do one thing really well, and not waver for that but rather find ways to improve it, then you’re always winning in my eyes. I’d say Andre 3000 because he was one of the last comedians. He could be himself one day, and play Jimi Hendrix in a film the next, and you not question it. It fits him. And then he turns up in a wig and a boiler suit. You don’t question if he just comes out with that.

OG: So in addition to the music, which is front and centre, what other projects are you coalescing around you?

KR: I’ve always dabbled in everything, especially at LCF [the London College of Fashion, where he studied], but going into this project, I really wanted to spend some time being a music artist. Really pushing myself and digging into what it takes to put together a great project, than ‘OK music’ wrapped up in this whirlwind of other things. I want things to complement the music and create a theme and a feel. People wouldn’t necessarily know that I do a lot of my music artwork myself. I’ve moved from photorealistic drawing and now my art style is a lot more crude, and that’s just because I find that my whole creative process is a bit more crude and haphazard. I needed to find a line or a sketch or a pen mark that could describe that as vividly as the music. So that’s where I’ve been trying to find myself now. We’re going to translate that into the fashion as well, and we’re already playing with the looks in the videos and visuals. I personally think I killed the game that day with the waistcoat over the blazer. The game stopped being played!

OG: Everyone else can go home!

KR: I won! And now we just finished the 2020 video, and with all the looks we were asking: ‘How do we exaggerate all this blackness to the max?’ I always go back to: what is representation? How important is it to people? Because I find now people are just satisfied with the idea of ‘OK, I’ve seen it, so that’s enough’. But what did we actually talk about by just seeing it? You haven’t gained anything. In terms of me there’s no such thing as using blackness. I am black. As soon as I step in front of the camera, I now represent something that should be a norm, but isn’t a norm doing something. So like, how do we extend that? And how do we do that? And how do we use fashion to complement it, so that it’s not just like a thing tacked on to the end.

OG: So the representation doesn’t come from you just being black, it comes from you channelling your history, your experiences...

KR: Your culture. The conversations we have, the ones we don’t have. And we’ve been trying to do that from the beginning. I feel like maybe I was a bit more heavy handed back in the day. I’m gently guiding people in now, that’s the vibe.

OG: So you’re charging £3 across all the shows for your next tour, why was this important to you?

KR: If you create a price point that makes it accessible to everyone, you eliminate this hierarchy that comes with ticket purchasing. There’s no barrier now to who can come and see a Kojey show. But then the scale of the shows get bigger very quickly. Even doing Scala after Cafe Koko is less people than we did last year. But what do you go to a show for? You go there to be really close, even if it’s just for an hour, to the artist you love, the music you enjoy, for the people that you enjoy being around when you listen to music. Making the scale of the shows smaller was intentional, so I can look people in the eye. Say: do you like this music as much as I do? Were you as gassed as I was in the studio this morning? I don’t want to be playing to people about five metres away from me, then behind a barrier, and then five metres behind that barrier, with security and cameras in front of me.

OG: It creates a weird disconnect between you and the audience.

KR: And I’m not really interested in having that. I remember I did a show at Brixton Academy, I walked off stage and said, ‘I will never do this venue again’. And that’s in the running order of shows you have to do. You have to do the Brixton Academy show, then you have to do this show and then you have to do that show. I said I’m not doing it. The people were too far [away], I didn’t like the sound, the building was too cold. I don’t enjoy it, I can’t do it. I want to go where I feel love in the building. And that’s what people will leave the show saying. It’s always love. Always love.

OG: A lot of your work is about love. It’s one of your great themes. What’s the best thing about falling in love?

KR: The best thing about falling in love is being vulnerable. I’m a Capricorn. I’m very stubborn, I’m like ‘allow it!’ ‘Come back!’ ‘What’s up there?’ ‘What’s down there?’ ‘I don’t like it.’ My approach to falling in love is very stubborn. And then all of a sudden you’re in love. You’re willing to let go of that rigidness, even if it’s just for a second. You can appreciate that.

OG: What do you want to see in the world as a result of your work?

KR: When I was a kid and I first found that love of music, the culture of swapping and sharing each other’s music, I was probably about 16 or 17. That feeling of difference, like you’re walking through life and everything feels different and all of a sudden you meet somebody, and then you’re playing a song and then one of my songs comes on and they go ‘you listen to Kojey?’ and they go ‘you listen to Kojey?’ and you’ve made a connection, you’ve made a friend over the music. You got a real interaction there. I think the young adult life is understanding that we’re expected to have all the answers but that’s virtually impossible. So figure it out with me, just going along with it. And then I think for the older generation, I want them to see the ambition of youth, the rebellious side, and how important it is to encourage that rebellion rather than stifle it, because it’s what made their generation, it’s what made the generation before that. And it’s just what’s making this generation. It’s a bit of a clusterfuck but we’re in it!

OG: So if you could hijack the future and remake the world as a utopia in Kojey’s image, what would that look like?

KR: Just mad statues of me, and you can go there and praise me for fixing this fucking world! The rest of it, would be a world without difference. That’s not to say that we make everybody the same, but that we teach people not fear difference. Fear is probably one of the first lessons that everybody gets taught, and we let that grow, like a seed. Instead of being taught to embrace difference, we’re taught to embrace fear. Fear makes us want to cling to survival and survival is a selfish thing – if you have the power to make the chips fall in your favour, you’re gonna [do] that, you’re not gonna think about everybody else. Rather introducing a world with true leadership that thinks about the greater good of everyone rather than the few... and the statues.

OG: What we expect from CASHMERE TEARS?

KR: Just how much we took it there. There were songs that got cut because we took it too far! It’s warmth, it’s service, it’s gratitude – it’s a bit of everything. And probably the singing – I sang a lot more on this project. Sometimes I play the project through for people and they don’t recognise it’s me singing. I think that’s what I’m saying – we took it there.

CASHMERE TEARS is out on September 13, 2019.

Grooming Michael Harding at D&V; Set design Ibrahim Njoya; Photographic assistant Tintin Jonsson; Styling assistant Marie Simon; Commissioning director Thea Charlesworth; Producer Jo Evendon.