The director’s death last week robbed British cinema of one of its most innovative and influential figures, as Paul Moody explains

- TextPaul Moody

Nicolas Roeg made films you can’t forget. From the druggy bohemianism of Performance, to the colour-coded horror of Don’t Look Now and the bleached-out landscapes of The Man Who Fell To Earth, his most iconic films haven’t just become part of popular culture. They haunt the subconscious, demanding you revisit them.

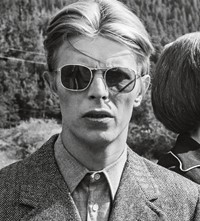

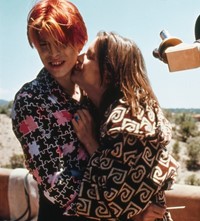

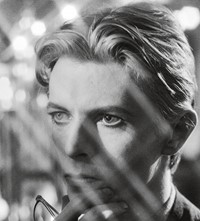

Who hasn’t dreamed – at some point in their lives – of swapping the humdrum nine-to-five for Mick Jagger’s decadent existence as Turner, holed up in his Notting Hill lair at 81 Powis Square? Or suspending reality like David Bowie’s Thomas Jerome Newton, spaced out in the desert, blitzed on cold martinis?

In Roeg’s films, nothing is quite as it seems. Taboo-busting themes of emotional detachment, identity, sex and death are mirrored by an elliptical, non-linear style which delighted film buffs, and, you can only assume, drove his studio bosses up the wall.

“A sick film made by sick people for sick people,” ranted the Rank Organisation, the film’s distributor, on seeing 1980’s Bad Timing – condemning this bruising examination of sexual and psychological warfare to obscurity prior to its critical re-evaluation two decades later. The infamous sex scene between Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie in 1973’s Don’t Look Now, meanwhile – which intercut scenes of the pair making love with post-coital clips of them getting ready to go out for the evening – troubled censors on both sides of the Atlantic. Roeg cut nine frames from the final print to avoid a disastrous X rating in the US – and it was entirely removed when the film first aired on BBC.

For Roeg, however, the point of these startling visual mosaics was to reflect not just the art on the screen, but reality itself. “It’s not just that particular drama, it’s life,” he told the BBC’s David Thompson in 2015 Arena documentary It’s About Time. “I like to feel a drama is all around us.”

Roeg might have been an original, but he learned at the feet of the masters. Born in London in 1928, he began his career as an editing apprentice in 1947, slowly working his way up in time-honoured fashion, from second-unit cinematographer on David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia to cinematographer on Roger Corman’s The Masque of the Red Death; and, in 1966, on François Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451.

It was 1970’s Performance, however – co-directed with Donald Cammell – which made his name. With Mick Jagger – then the biggest rock star on the planet – signed up to play the lead role, paymasters Warner Bros. were expecting a swinging London-style caper along the lines of The Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night. What they got was a hallucinatory fin de siècle bad trip containing scenes of graphic sex and violence, set to a soundtrack of swampy guitars and hip-hop forefathers The Last Poets.

As disorientating as the magic mushrooms Turner and satanic consort Pherber (a mesmeric Anita Pallenberg) feed their house guest, Chas (James Fox), an East End gangster on the run, it was almost buried by an appalled Warner Bros. The director’s cause was hardly helped by a review in The New York Times which read: “You do not have to be a drug addict, pederast, sadomasochist or nitwit to enjoy Performance, but being one or more of those things would help.”

It is now, of course, the definition of a cult classic. But you can’t help but feel Roeg’s singular vision would always lead him away from the mainstream. Having spent 20 years within the studio system – bookended by 1971’s Walkabout and 1990’s The Witches (denounced by author Roald Dahl) – he drifted to the margins, making a string of made-for-TV movies before returning, belatedly, with 2007’s Puffball, adapted from a novel by Fay Weldon.

His ability to conjure up unforgettable scenes, however, never deserted him. From the climax of 1983’s Eureka, where prospector Jack McCann (Gene Hackman) is washed away by a tidal wave of gold in the Canadian wilderness, to the crackpot exposition of the theory of relativity by Marilyn Monroe (Theresa Russell) in 1985’s Insignificance, his films live on in the imagination long after the latest blockbuster has faded.

Let the film buffs argue about his influence on directors such as Christopher Nolan, Ridley Scott, Mike Figgis and Danny Boyle. For us humble film fans, he will always be one of a kind.

Farewell Nic, you old rogue.