A new book attempts to shine a light on homosexuality and queerness in Japan

- TextMiss Rosen

In 2013, Sara Giannini and Jacopo Miliani were in Tokyo to attend a performance program organised by the research group OuUnPo. On their very last night in the city, they discovered a homoerotic photo story from 1978 sitting on the shelf of a small sex shop in Shinjuku Ni-chōme. The cover showed two men, set against the sea, touching each other intimately. Inside, an illustrated story of love and desire began to unfold in a curious and compelling way.

“In Japan any visual representation of sex organs is scratched away, blurred, or masked,” Giannini recalls. “This photo story, however, performed a different kind of omission. Ocean waves or seagulls were subtly used to cover, and yet reveal, the organ of male love [and] the obstructions imposed by censorship were triggers of sensual desire, complicating the relationship between the seen and the unseen. Although the author of the magazine remains a mystery, according to what we have been told, it may be the work of underground photographer Kurō Haga, founder of BON magazine.”

Intrigued, Giannini and Miliani began a journey into a world wholly foreign to their own, one which has culminated in the publication of Whispering Catastrophe: On the Language of Men Loving Men in Japan (SelfPleasurePublishing in collaboration with OuUnPo). Here, they share their experiences creating this book.

How has censorship changed the ways in which ‘men loving men’ is represented in Japanese art and culture?

Sara Giannini: Censorship has limited the expression of sexualities and identities that deviate from the norm. At the same time, many makers of homoerotic content have challenged those conventions and been able to express their desires not only despite censorship, but through it. That’s not to say censorship has had a positive influence, but rather to appreciate the potential of ungraspable, whispered and tactical forms of resistance.

What were some of the challenges you faced in creating this project?

Jacopo Milian: Starting from censorship, obstacles were the main creative constraints of the book. Two white authors coming from the West, not speaking Japanese and still wishing to deal with the construction of an identity that doesn’t belong to them. This sounds very problematic and constitutes a very risky condition. We decided to jump into the unknown in order to deconstruct our own language and identity.

What were some of the surprises you discovered in making this work?

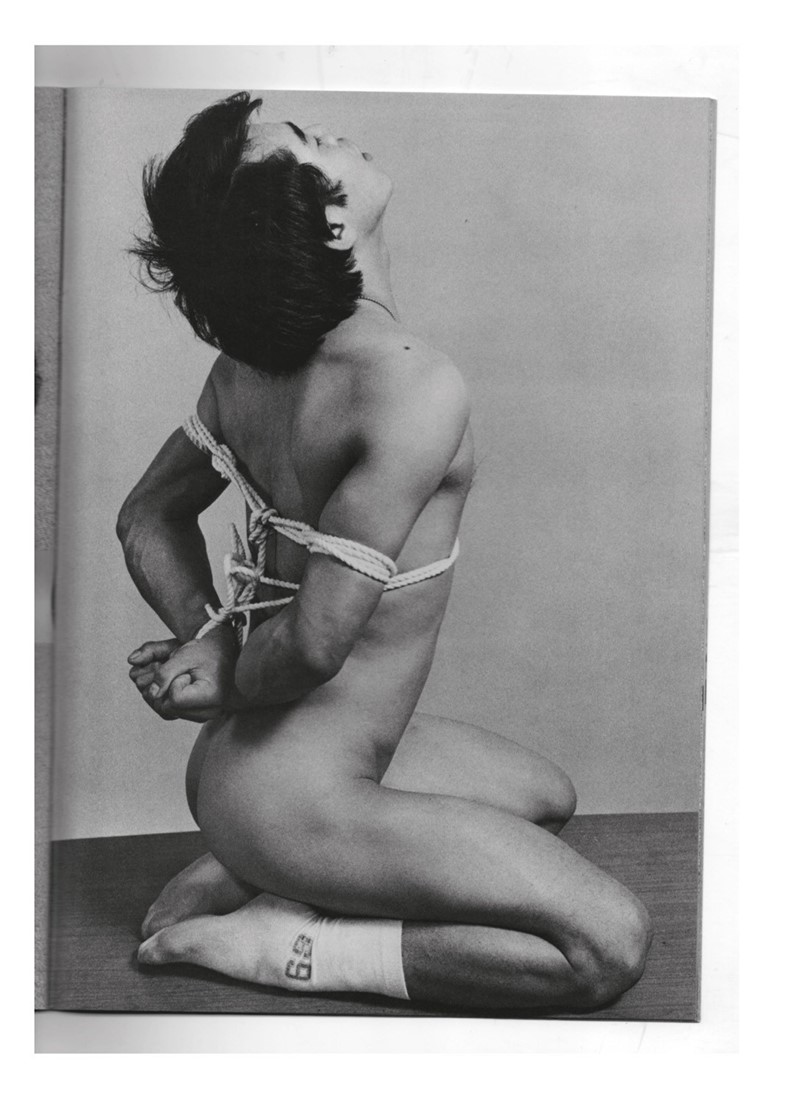

Sara Giannini: One could say that the making of the book was dictated by surprises and serendipities. Perhaps one of the most pleasant ones for me was the periodical Le Sang et la Rose (Chi To Bara): Revue de Érotologie, Homosexualité, Sadisme, Masochisme, Fétichisme, Narcisisme, Infantilisme, Magie, Occultisme, Humour Noir, Complexe Psychisme, which hints at the very particular link between non-normative forms of sexuality and occultism that characterised the dialogue in the 1960s and 1970s.

Published between 1968 and 1969, the magazine mixed European mannerist paintings, shunga prints, bondage and S&M scenes, sections about witchcraft, demonism, and vampirism, as well as essays from disparate historical and cultural backgrounds.

How did the underground subculture of the gei bōi become a vital space for ’men loving men’?

Jacopo Milian: The gei bōi were an underground subculture from the 60s. They were effeminate boys mostly in their late teens, wearing fashionable female items and serving their clientele at the bars. For their style, they looked to the West opposing their attitude to the danshō, street male prostitutes wearing traditional female costumes.

Gei in Japanese not only is the transposition of the English word ‘gay’ but is also part of the gei no kai (world of entertainment) and is distinguished from everyday life. I am convinced that the gei bōi played with the ambivalence of the term and they used their creativity and style as a political act.

How did Tōgō Ken become a significant political figure in the queer activist movement?

Sara Giannini: Tōgō Ken is regarded as one of the first gay activists in Japan. In the late 1960s he resigned from his job in a bank, deserted his wife and children, proclaimed his homosexuality, and opened a gei bar. As a radical political gesture, Ken appropriated the deprecatory term okama (faggot), naming himself ‘Okama Tōgō Ken,’ reclaimed cross-dressing as a political act, and directly flaunted jōshiki (common sense), advocating freedom for all members of society.

Tōgō Ken descended from an ancient noble family; his father and stepfather were both in the parliament and he also ran in the national election several times between 1971 and 1995. He spread his political vision through his magazine Za Gei (The Gay), where he wrote against censorship and continued to depict male nudity. He was repeatedly arrested for publishing images of genitals. Although he was never elected, Ken continued to fight against jōshiki all his life, setting the ground for the future activist movements.

What was the impact of the gei bōi subculture?

Jacopo Milian: I don’t think the gei bōi ever became a mainstream phenomenon, but in the 90s Japan experienced a so-called ‘gay boom’ (gei bumu) and everything related to ‘men loving men’ became trendy and fashionable. As with any mass media trend, there were many commercial purposes behind this interest and the presence of this topic in to mainstream Japanese society not always was accompanied by a philosophical and political reflection. That was for example very similar to what happened in the in the West… don’t you think?

Whispering Catastrophe: On the Language of Men Loving Men in Japan is out now via SelfPleasurePublishing.