Jeremy Deller: ‘The State Always Says Music and Culture Is the Problem’

- TextLiam Hess

The Turner Prize-winning artist discusses his new documentary which explores British rave culture in the 1980s and early 1990s, drawing parallels to today

While he is best known for winning the 2004 Turner Prize, and representing Britain at the Venice Biennale in 2013, you’re more likely to find Jeremy Deller reenacting a miner’s strike in a remote, sodden field than exhibiting on the walls of a blue-chip Mayfair gallery. Over the past three decades, Deller has quietly expanded the possibilities of public art: whether setting up a giant bouncy castle at Stonehenge or staging a nationwide ‘living memorial’ to the Battle of the Somme, his forays into the murky terrain of British social history have enjoyed popularity beyond the art crowd, thanks to their unpatronising playfulness.

It’s an attitude that carries through to his latest project: a documentary titled Everybody in The Place: An Incomplete History of Britain 1984-1992, commissioned by Frieze and Gucci to screen at this year’s Frieze Art Fair. The film is a return to the dance music he memorably explored in his series Acid Brass, where he collaborated with a Stockport-based brass band, fusing their music with acid house and Detroit techno. This time, Deller turned his lens to the seismic impact of British rave culture in the 1980s and early 1990s.

“It happened at a pivotal moment, just as Margaret Thatcher was beginning her decline,” he says following a screening of the film. “I think it was a celebratory goodbye, but also a hello to something else that might be coming. It wasn’t just about partying: it changed licensing laws, it liberalised the public attitude to drugs. It can’t be separated from history.” Often in Deller’s work the relationship between past and present is implicit, but in this documentary the parallels are more obvious: archival clips are intercut with footage from a sixth-form college where, earlier this year, he presented a group of A Level politics students with a history of rave culture and recorded their responses.

“I just thought it would be interesting to show a group of young people at a very important moment around 30 years ago, where young people took a lot of initiative,” he explains. The demographic of this college is largely Muslim, and he notes the uncertain future facing minorities in 2018. “With Brexit and the rise of the far-right in Britain, it’s not clear really what the next decade will hold for any of us, but particularly for a 17-year-old Muslim kid. We don’t know what direction the country is going to take, so in that way I felt it was a similar time to then, a divisive time.”

Deller’s whistle-stop tour of house music’s history, from the black gay clubs of 1980s America to its surge of popularity in Thatcherite Britain, draws responses from the hilarious to the genuinely moving. A salient point is made by a female student who suggests the government’s attitude to rave culture (it probably goes without saying, but their plan was to shut it down at all costs) is part of a wider culture of blame, where music is used as a scapegoat for trends an older generation don’t understand. It recalls Marilyn Manson’s dismissal of the media’s accusations that goth rock was responsible for the Columbine massacre and, more recently, that drill music is to blame for the surge in violent crime in London. “It’s always happened,” says Deller. “The state weighing in on culture or music as being the problem. They say the problem isn’t housing or education, it’s actually these songs. Something gets blamed so we don’t have to look at the root causes.”

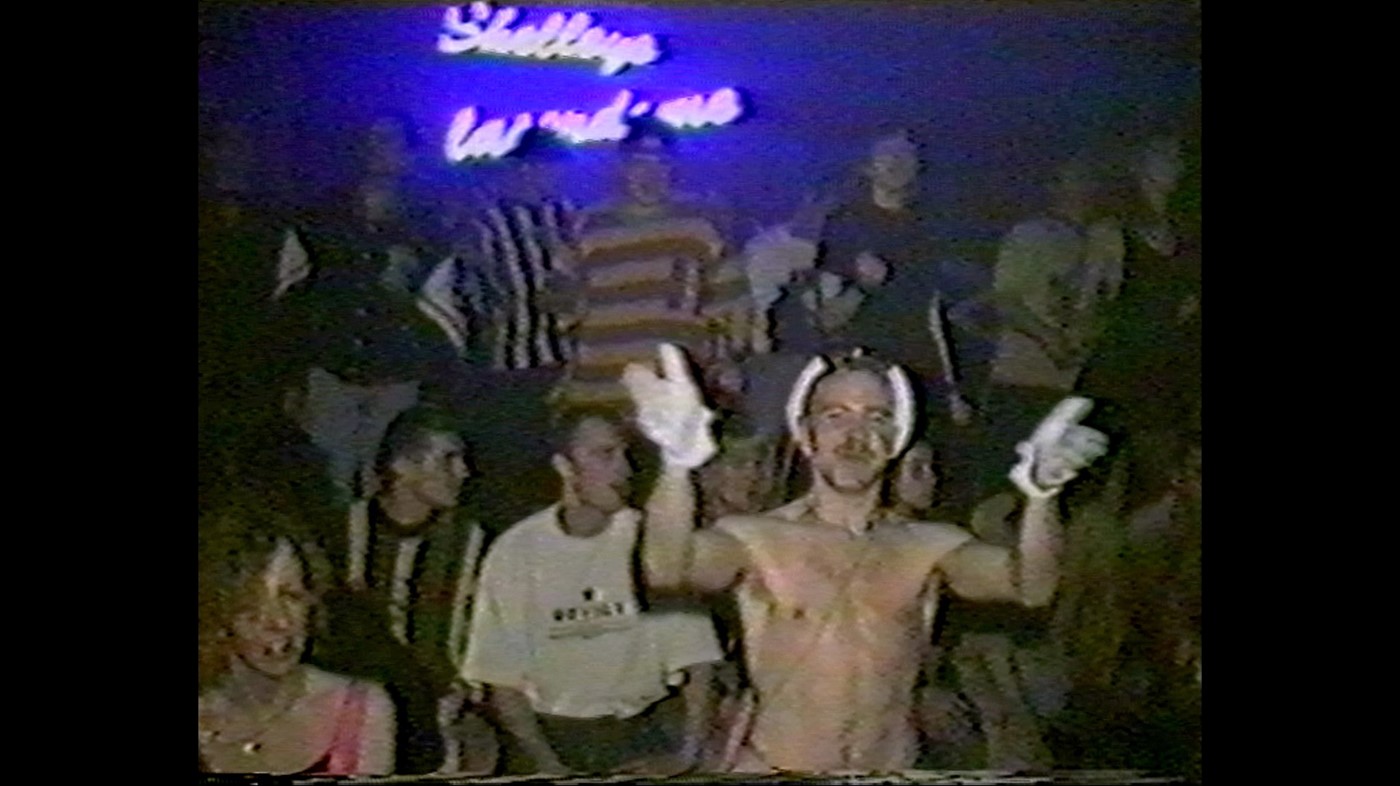

More joyous moments come via footage from lesser-known corners of British counterculture: of course, there are clips of the sweat-soaked raves (drugs are rarely mentioned, but implicit in the glazed stares and frantic gum chewing), but also an insight into the New Age travelling communities that blossomed alongside the movement, moving between sacred pagan sites in campervans. It’s a reminder that where many artists see it as their responsibility to document the present, Deller’s outlook is more reflective. “I think it takes a bit of time for people to really understand what’s happening,” he says. “You have to wait ten years to see what happens a decade after that scene or that moment, to see how Britain might have changed.”

At the end of the documentary, to the surprise of the classroom, the lights go down and a laser show kicks off to the thumping bass of Sined Roza’s Italian house banger I Don’t Know What It Is. Perhaps presenting this story of youth-led upheaval in a classroom setting is more subversive than it initially seems. Was Deller trying to remind them of this precedent: that previous generations have rebelled to enact change at a grassroots level?

“The school is quite academic, quite strict,” he says, after a pause. “I think that is the subtext, though. To show these hard-working young people that there is that possibility. They probably know it anyway, but it’s good to remind them that pop culture is woven into the history of the country, and that they have the opportunity to make change.” Even if it conforms to the documentary format, Everybody in the Place is a work of public art in the truest sense of the term: generous, inclusive, optimistic, and a rallying reminder that the youth still have the possibility to – for want of a better phrase – take back control.

Everybody in The Place: An Incomplete History of Britain 1984-1992, commissioned by Frieze and Gucci, will screen at Frieze Art Fair at 4-6pm on Sunday, October 7, at Auditorium at Frieze London, Regent’s Park, NWI 4LL. Frieze tickets give the public access to the screening.