The Story Behind Punk’s First Art Exhibition

- TextMiss Rosen

Featuring live tattooing and a ‘rectal’ portrait of Andy Warhol, Punk Art was an exhibition like none that went before it. To mark its 40th anniversary, we speak to the curators behind this iconic show

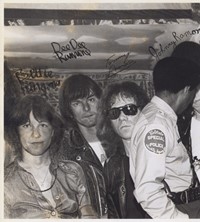

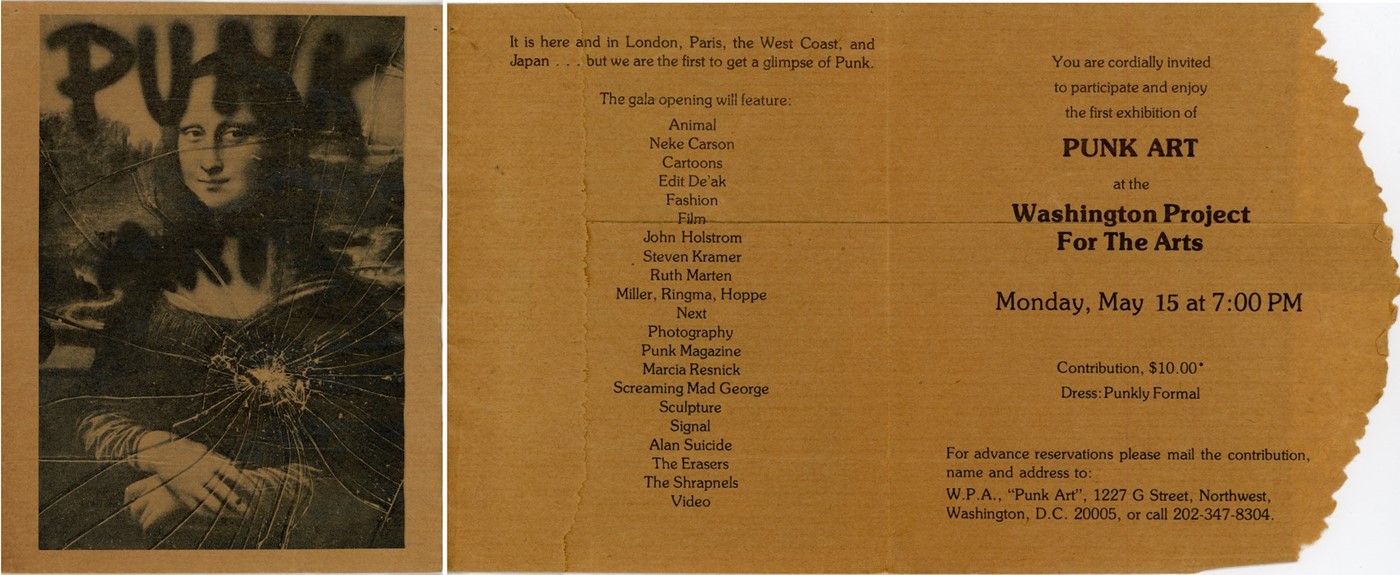

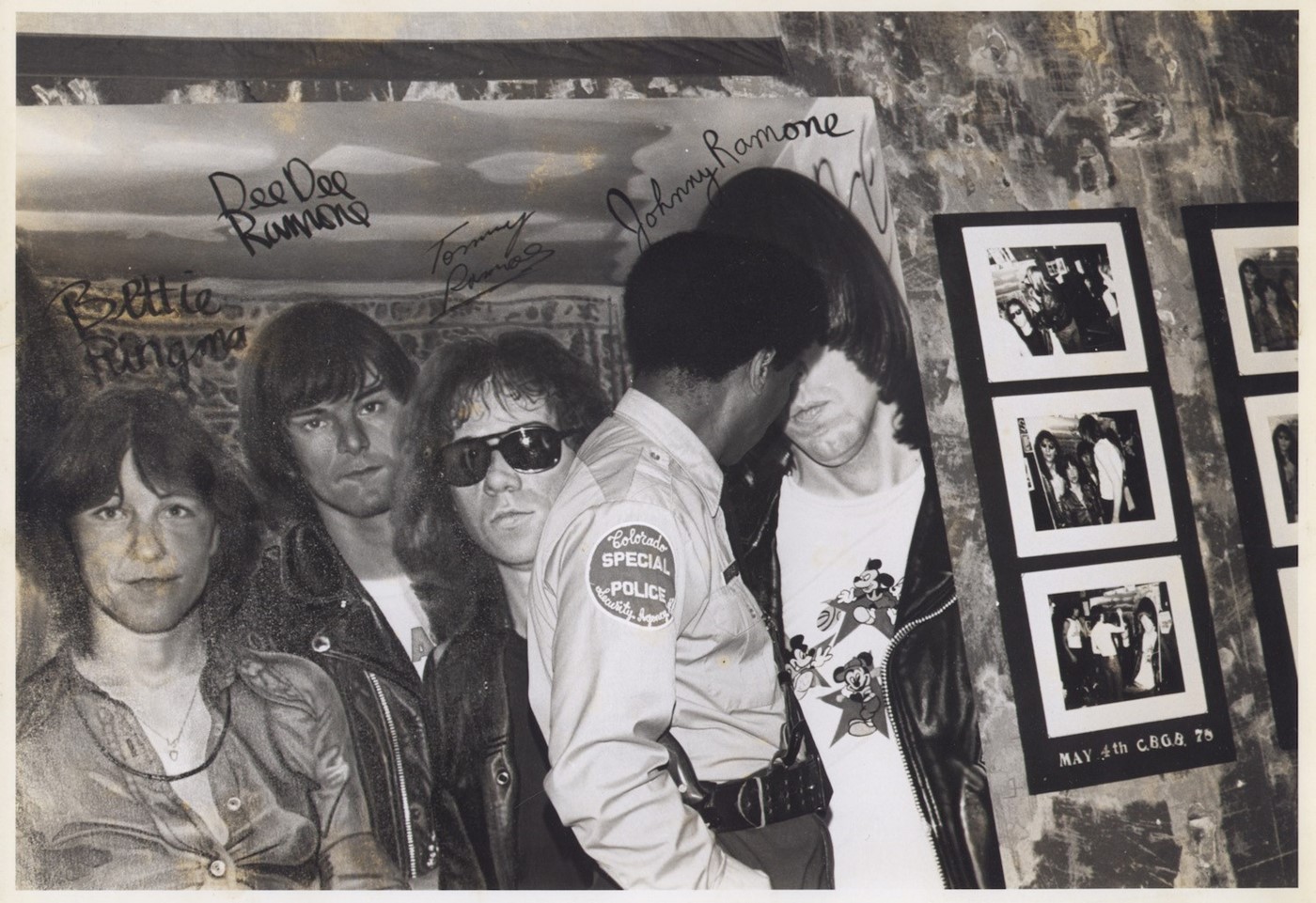

Today marks the 40th anniversary of Punk Art, the first exhibition to showcase the visual artists of a revolutionary new scene. Co-curated by Marc H. Miller and Bettie Ringma, the seminal 1978 show featured a stellar line up of talents from the burgeoning New York scene.

From Blondie’s Chris Stein, Suicide’s Alan Vega, and Ramones’ art director Arturo Vega to photographers Roberta Bayley, Marcia Resnick, and Jimmy DeSana, filmmaker Amos Poe and tattoo artist Ruth Marten, Miller and Ringma invited some of the most innovative and original artists of the time to install their work at Washington Project for the Arts in Washington, DC, an alternative arts space run by Alice Denney, who conceptualised it in the same vein as PS1.

“A whole new generation were making themselves felt and replacing the earlier generation that had emerged in the 60s. We realised that if things were going to happen, we were going to have to do it ourselves and it made perfect sense to say, ‘Okay, we can get a whole new art movement going.’ Feminist art was the model: it was more about an idea and an attitude than a specific style,” Miller explains.

As the definition of ‘punk’ was never established and it continues to evolve to this very day, identifying its ideas and attitudes required exquisite diplomacy. To curate an exhibition titled Punk Art “was a slightly dangerous thing to do in terms of getting a negative backlash. It was not so much from the general public – to a certain degree that was the point – but from the group itself,” Miller admits.

“Everyone had professed a purity and idealism. There was a strong anti-art aspect to what was happening at CBGB. The name ‘punk’ existed before the selection of people that would go under that name. Our first concern was making it authentic.”

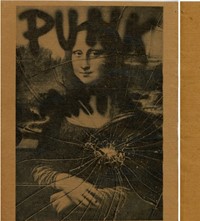

Miller and Ringma decided to hone their focus exclusively to the artists who were either in a band, connected to a band, or in the audience at CBGB. They first approached John Holmstrom and Legs McNeil, publishers of Punk magazine – the very people who introduced the word ‘punk’ to the world.

“Getting them on board was surprisingly easy. They were probably ten years younger than the people that I knew coming out of Soho and enthused about the idea. As it turned out, they weren’t rebelling against being accepted by the art world. John was a pleasure to work with and Legs was great at personifying an attitude and aesthetic,” Miller reveals.

“Then we picked and pulled from within CBGB. Everyone had their claim to the title of being a punk and we went with their works. Half the reason they went along with the show was because it wasn’t in New York. There was this sense that, ‘We are going to invade Washington!’”

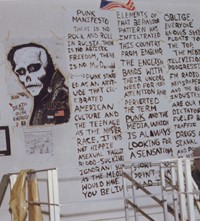

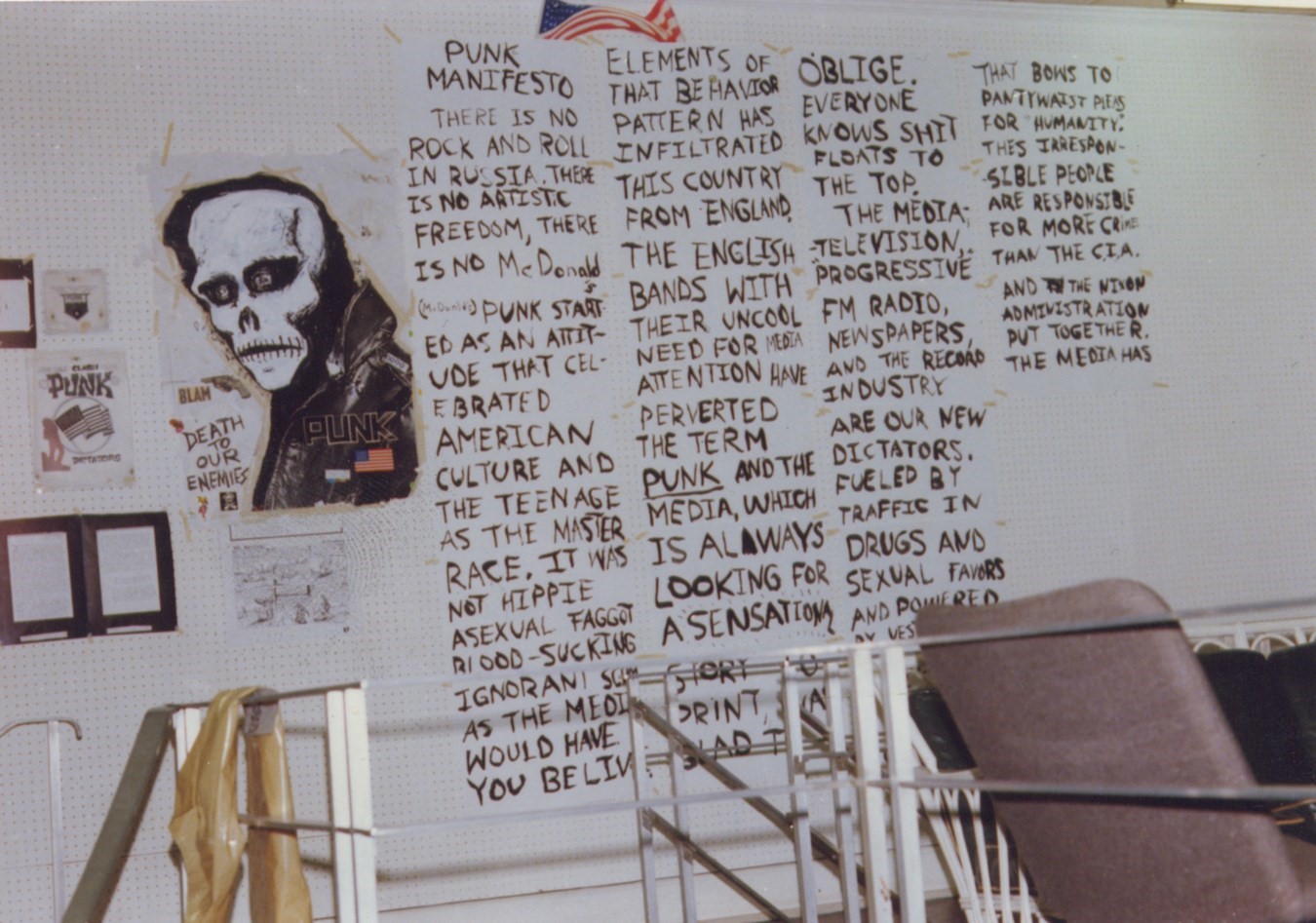

And invade they did as Legs McNeil took his Punk Manifesto to the streets of the nation’s capital during the height of the Cold War. “Basically Legs was saying, ‘There is no rock and roll in Russia!’ Then he lead a group of punks to the Russian Embassy and started throwing McDonalds hamburgers at them. It got treated like a national security threat,” Miller laughs.

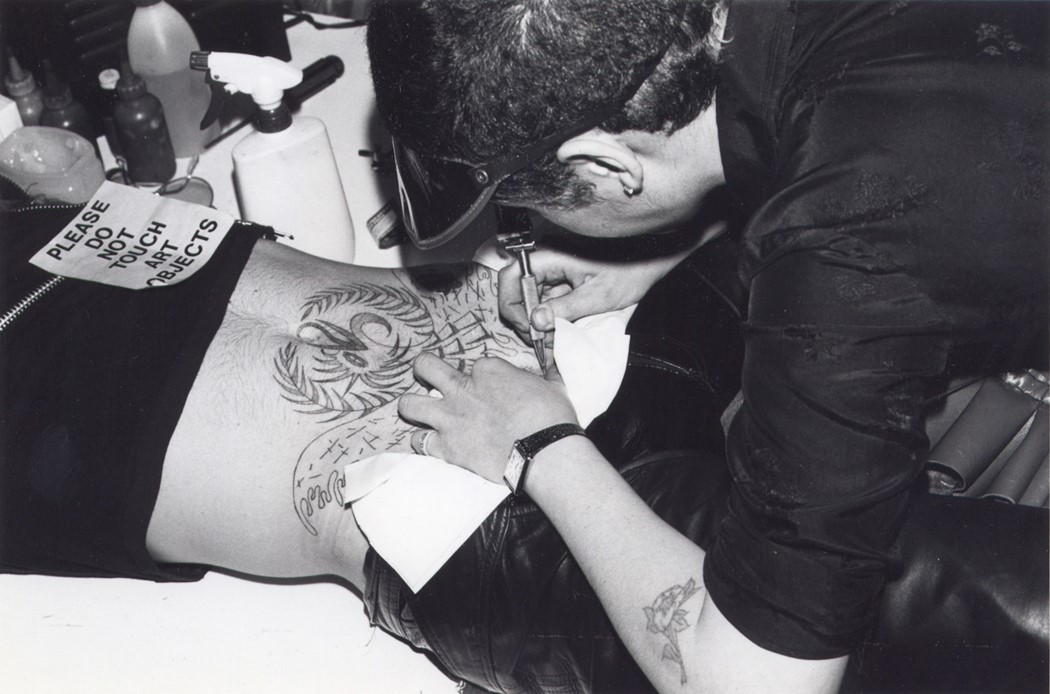

Mischief and hi-jinks pervaded the show. Ruth Marten did live tattooing while Steven Kramer’s Destructive Mouse, a big heavy piece of metal that moved erratically around the floor hitting people in the shins. Nicky Carson’s Rectal Realist portrait of Andy Warhol, which he did by putting a paintbrush up his ass and Andy Warhol sat for it, was hung alongside a video of the portrait session.

“We had stuff but nothing to cause the world to tremble in fear,” Miller admits. Yet, the title of the show alone made the public nervous. An anonymous tipster called in a fake bomb threat and forced an evacuation before the show opened to the public.

Despite the fear of a punk planet, no actual damage had been done until the fateful “Baltimore Weekend,” when John Waters and Edith Massey AKA the Egg Lady, came to town. The film screenings and live performances were overshadowed by the theft of Carson’s painting of Warhol.

“It became a cause célèbre,” Miller remembers. “Local radio stations started making regular please for the painting’s return. Eventually a high school kid sheepishly showed up and gave it back, so the story had a happy ending.”

Now, on the 40th anniversary of Punk Art, Miller looks back on this pivotal moment in time, just as everything began to shift. “It started out as a bit of a hype but a hype we all believed in,” he explains. “After the show, the character of punk changed in part because of British punk. Their concept was more political and working class, and whatever fears people had about the term ‘punk’ were magnified by the deaths of Nancy Spungen and Sid Vicious. ‘Punk’ quickly became a dirty word.”

Yet, for all the efforts of the mainstream media to malign the movement, it not only survived but continues to thrive, adapt, and grow, creating a fresh and fearless outlet for the next generation of rebels and radicals.

Miller reveals, “We believed there could be a Punk Art movement that would like its place alongside Pop Art and Minimalist Art – and the term is still being used. We learned that if things are going to happen, we are going to have to do it ourselves.”