As a new exhibition exploring the hoodie opens in Rotterdam, James Grieg explores the garment’s complex legacy

- TextJames Greig

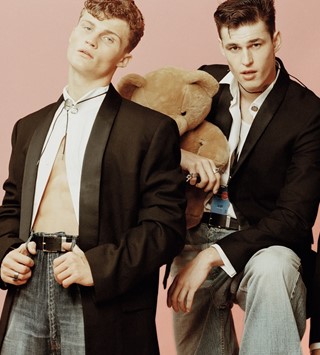

The hoodie is simultaneously the most banal and controversial of garments. Depending on who’s wearing it, it’s something thrown on for a hungover trip to the corner shop, a symbol of Zuckerberg-era corporate power, or the site of all sorts of questions about race, class, and discrimination. The Hoodie, a new exhibition opening on December 1 at the Het Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam, interrogates the cultural context surrounding this ubiquitous item of clothing, employing artworks, photography, found objects, filmmaking and, of course, the garment itself.

Rather than offering a definitive history of the hoodie, the exhibition instead looks to use it as a means of discussing the issues surrounding it. “In the UK, the hoodie is very much tied to class and youth,” Lou Stoppard, the exhibition’s curator, says. “Before I started working in fashion, I briefly interned at Sky News and was working there during the London riots. Whenever a video editor was picking a still for their report, it would inevitably be a young guy in a hoodie. I also grew up during the ‘hug a hoodie’ period.”

Despite the fact that David Cameron never actually said it, ‘hug a hoodie’ remains one of the most enduring emblems of his leadership. The phrase began as a caricature of a speech Cameron made in 2006, in which he attempted to refashion the perception of Tories as being callously harsh on young criminals:

“We – the people in suits – often see hoodies as aggressive, the uniform of a rebel army of young gangsters. But, for young people, hoodies are often more defensive than offensive. They’re a way to stay invisible in the street. In a dangerous environment the best thing to do is keep your head down, blend in, don’t stand out.”

This appeal to empathy wasn’t entirely incorrect, although little the Conservatives did when they eventually gained power was in keeping with it. The following year, Cameron made a visit to the Benchill estate in Manchester, where a young man in a hoodie pretended to shoot him with his fingers. This led to one of the most iconic political photographs of the decade, as well as any number of smug ‘Still want to hug a hoodie, Dave?’ tabloid headlines. The incident features in a film on display in the exhibition, which brings together different media depictions of the hoodie.

It’s easy to forget now that, in the mid-00s, the hoodie was the subject of a full-blown moral panic which lasted for years. A quick look at the BBC news archive from this era brings up an absurdly long list of stories and controversies; the Archbishop of York, for instance, once gave a speech at a secondary wearing a hoodie, making the helpful interjection that “99 per cent of those who wear hoodies are law-abiding citizens”. In Scotland, meanwhile, Angus council commissioned a bronze statue of a hooded teenager and was accused by furious local residents of “glorifying hooligan culture”. In 2005, an incident as banal as the decision of a shopping centre in Kent to ban hoodies led to a national debate, with deputy prime minister John Prescott declaring hoodies “intimidating” and publicly backing the ban. He also confessed to having narrowly avoided a ‘happy slapping’ – truly, this was a halcyon age.

During this period, ‘hoodie’ became a term to refer to the people who wore the garment, roughly synonymous with ‘chav’. It was part of a classist cultural landscape which included Little Britain’s Vicky Pollard (a cruel caricature of young, working-class single mothers) and horror film Eden Lake, a Daily Mail fever dream in which a nice middle-class couple are terrorised by a group of hoodies and, of course, their rottweiler. It was a time of widespread concerns about ‘anti-social behaviour’, when people talked about loitering, playing loud music or dropping litter with a level of outrage which is today reserved for knife crime. Throughout all this, the hoodie became a symbol of societal decay – the national costume of ‘Broken Britain’.

All of this would seem almost quaint, were it not for the fact that young black men in the UK, and elsewhere, are still being vilified for wearing hoodies. The moral panic isn’t over yet. At the 2015 Brit awards, Kanye West brought on an array of grime stars, most of whom were wearing black hoodies, and was accused of “promoting gang culture”. The murder of Trayvon Martin (who was wearing a hoodie when he was shot, in Miami, in 2012), brought into focus the extent to which wearing a hoodie could endanger young black men; how certain types of clothing play into racist stereotypes about who poses a threat.

A protest rally organised in response to Martin’s murder, the Million Hoodie March, also showed that the garment could be used as a tool of resistance – Stoppard says this event was one of the inspirations for the exhibition. Earlier this year, MP David Lammy took part in a similar campaign called ‘56 Black Men’, in which a number of black men in prominent positions were photographed wearing hoodies. The series aimed to challenge the stereotype that black men in hoodies are dangerous, which suggests that the hoodie still bears a potent symbolic value.

Stoppard is sceptical as to whether the increasing ubiquity of the hoodie has done anything to mitigate the underlying causes of cases like the ones outlined above. “The hoodie might be normalised to an extent but there are still issues of class, stereotyping and inequality,” she says. “There are a lot of people who can wear a hoodie and move through the world unaware of these issues, and then there’s other people for whom the hoodie is an extension of the stereotypes and prejudices they already face. But these stereotypes aren’t just around the garment itself.”

While we may still think of the hoodie in relation to class or race, or any number of subcultures (hip-hop, skating, graffiti, to name but a few) it has also, in certain contexts, supplanted the suit as a symbol of corporate power. “Look at the world of tech and Silicon Valley,” Stoppard says. “Someone like Mark Zuckerberg chooses a hoodie because of its associations of being an outsider. He’s trying to suggest: ‘I’m not a suit like you. I’m not a typical banker.’ But still, the hoodie has emerged within those spaces as the everyday wardrobe of powerful men.” Whether the hoodie can retain its position as a symbol of counter-culture when it’s increasingly associated with profoundly uncool tech CEOs remains to be seen.

For Stoppard, the topic is so multi-faceted that it was important to approach it through various different angles. “Lots of contemporary artists have engaged with the hoodie as a theme within their work, including David Hammons, John Edmonds, or Prem Sahib,” she says, “but there’s also a lot of historical fashion within the show, because it’s interesting to look at how some of the associations we have around the hood today, such as secrecy or privacy, have their roots in the symbolism of hooded garments from the past.” In its use of different mediums and thoughtful consideration of socio-political contexts, The Hoodie marks an admirable effort at expanding what a fashion exhibition can be.

The Hoodie is at Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam, from December 1, 2019 – March 12, 2020.