The Sexy, Secret History of Leather Fetish Fashion

- TextLouis Staples

From post-war motorcycle groups to modern-day sex apps, this is the story of how leather became a symbol of masculinity and sexuality

This article is part of a series on AnotherManmag.com that coincides with LGBT History Month, shining a light on different facets of queer culture. Head here for more.

“When I’m wearing my leathers, I like the way I get to be such a symbol, a trope, of masculinity and sexuality,” explains Max, a 38-year-old gay man from London. Max is a “leatherman” or “leatherdaddy”, two common descriptors for gay and bisexual men who fetishise leather clothes and accessories.

“Fetish fashion” is the term used to describe the intrinsic link between clothing and sexual fetishes, with materials like leather, lace, latex, and rubber holding particular prominence. Dr Frenchy Lunning, author of the 2013 book Fetish Style, writes that fashion has historically been the easiest way to “traverse” from one spectrum of fetish to the other. Lunning gauges that, in the history of fetish fashion, there have been two climaxes – no pun intended – with the first occurring between 1870 and 1900. “The Victorians went crazy over silk and velvet,” writes Pat Califia, author of Public Sex: The Culture of Radical Sex. “As quickly as new substances were manufactured, somebody eroticised them.”

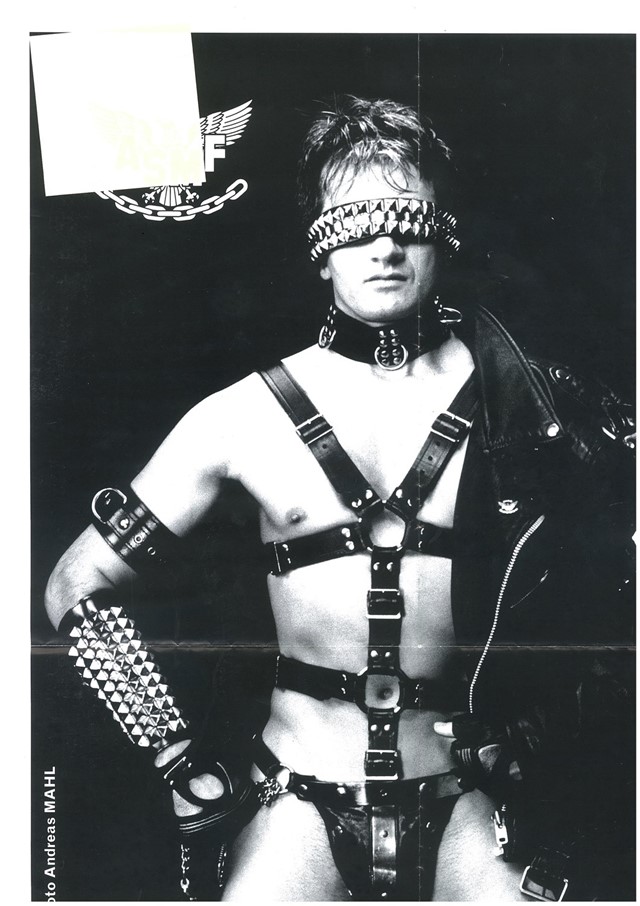

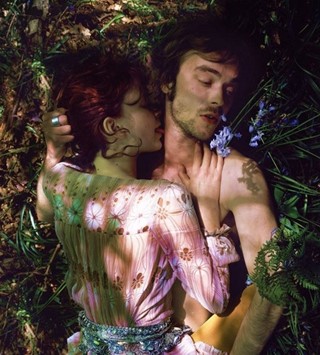

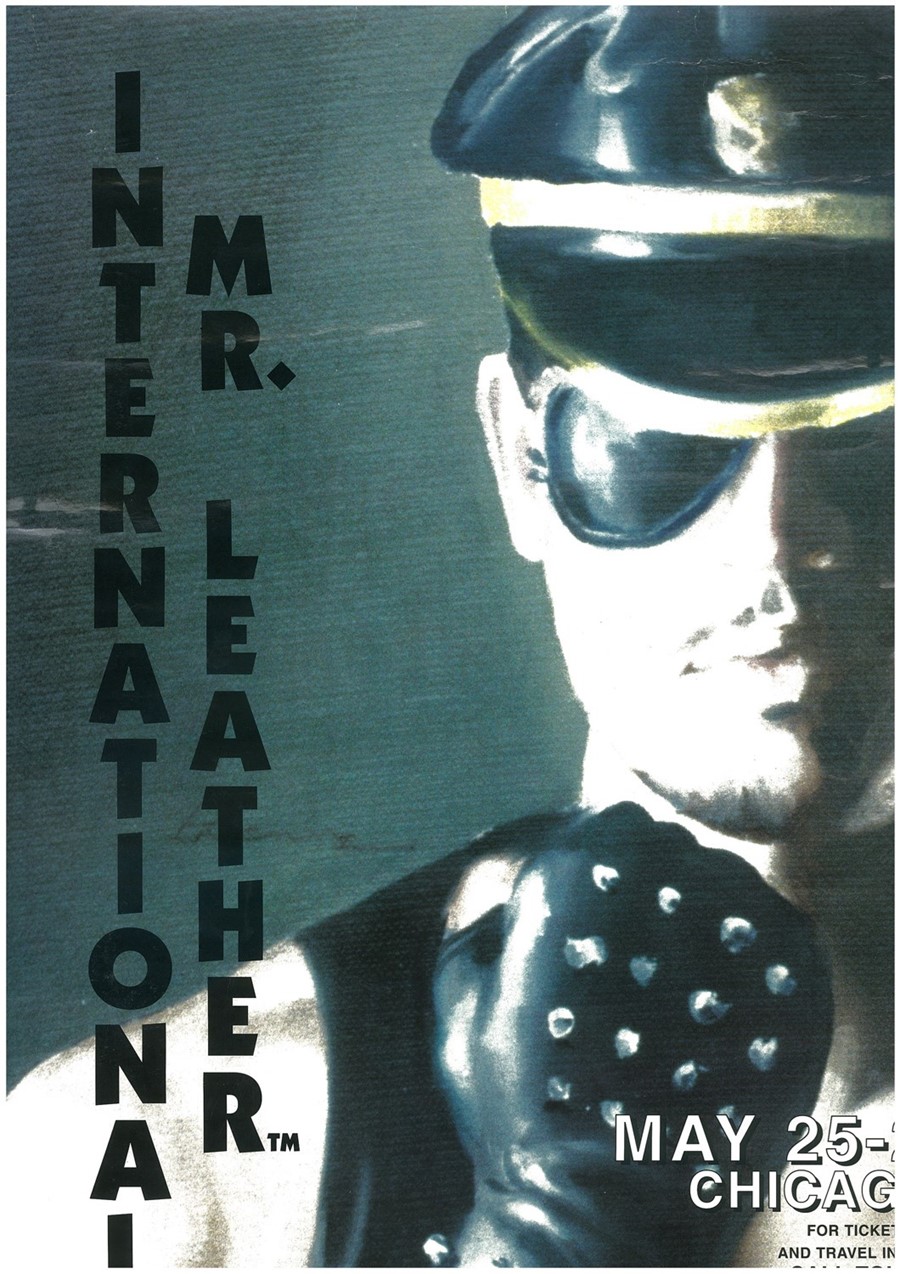

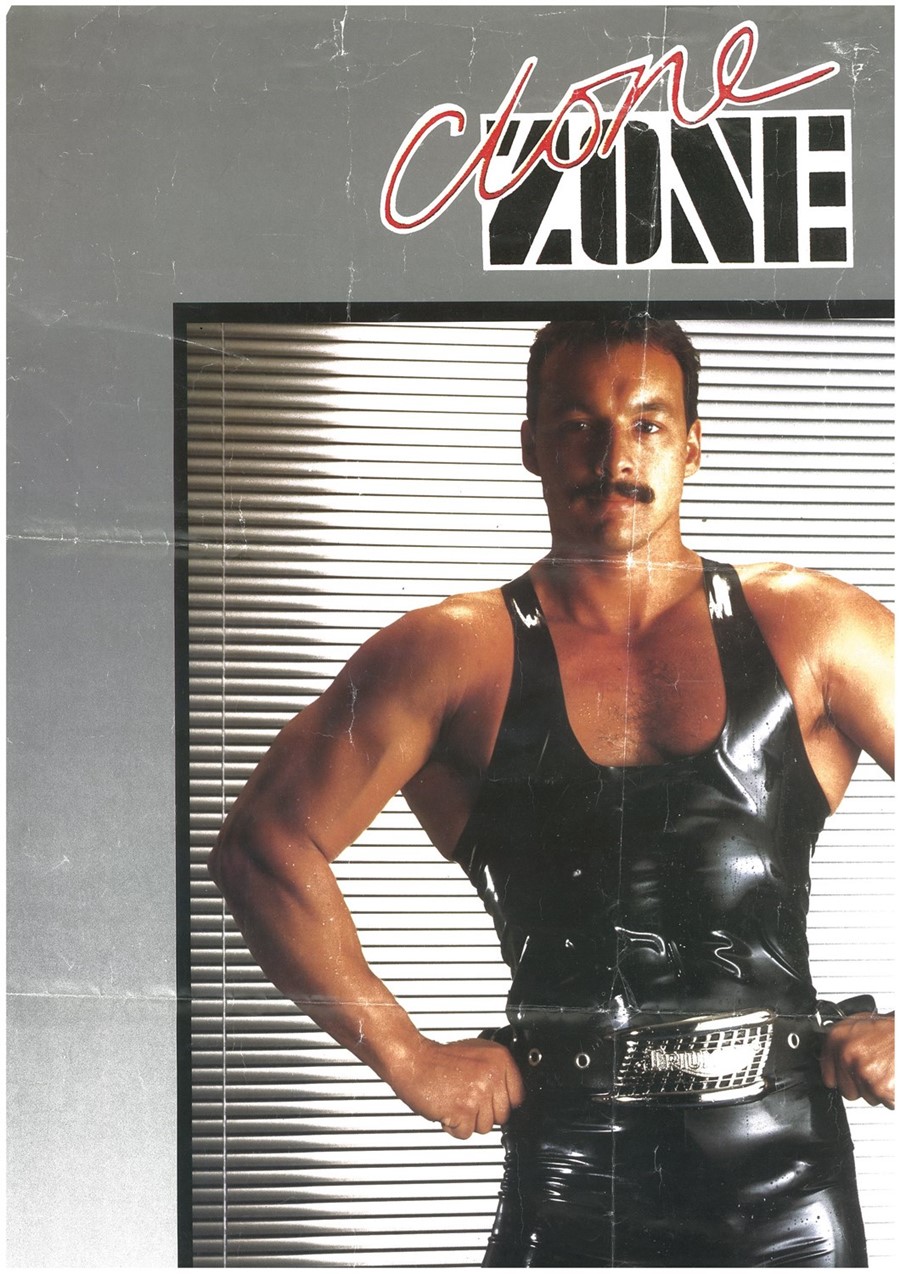

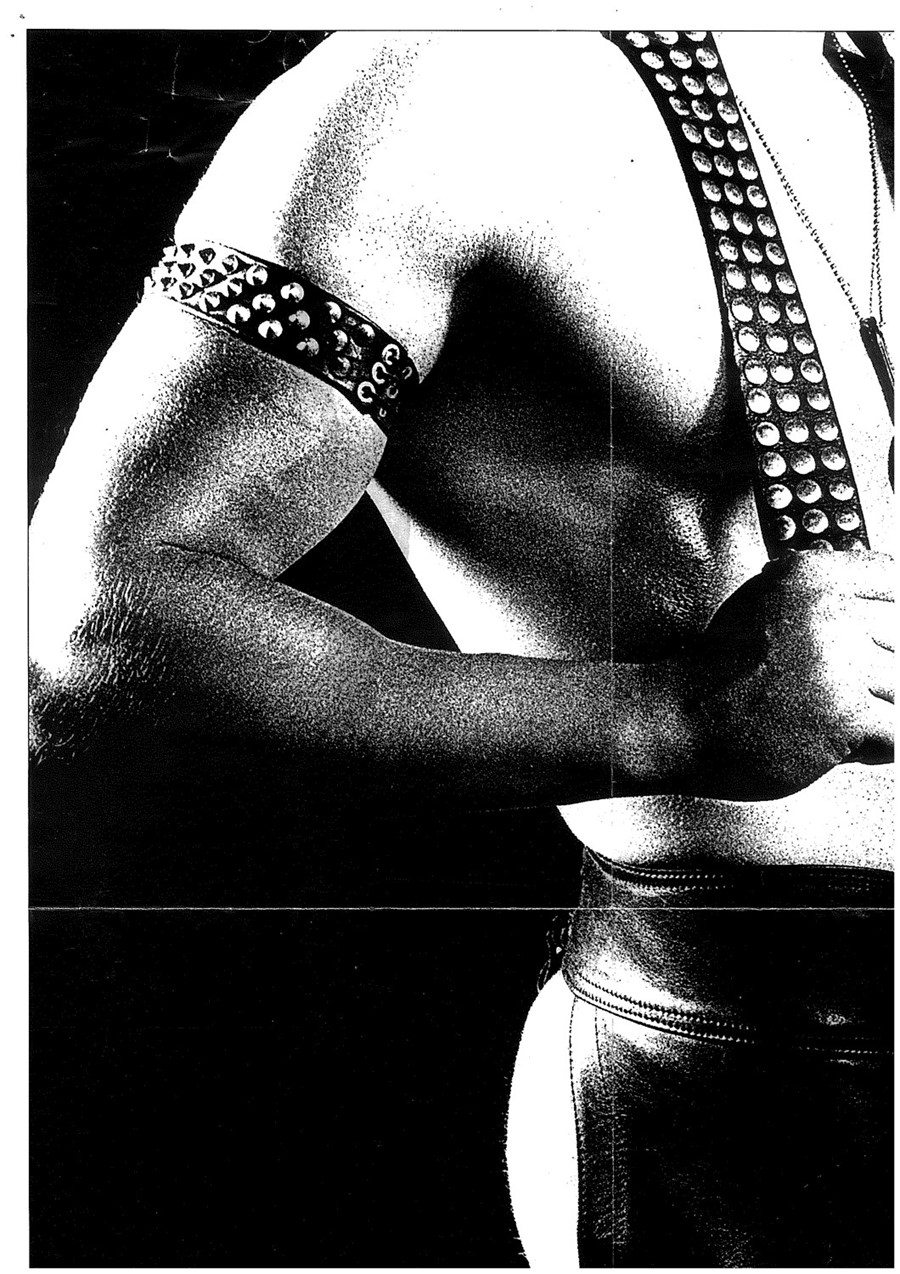

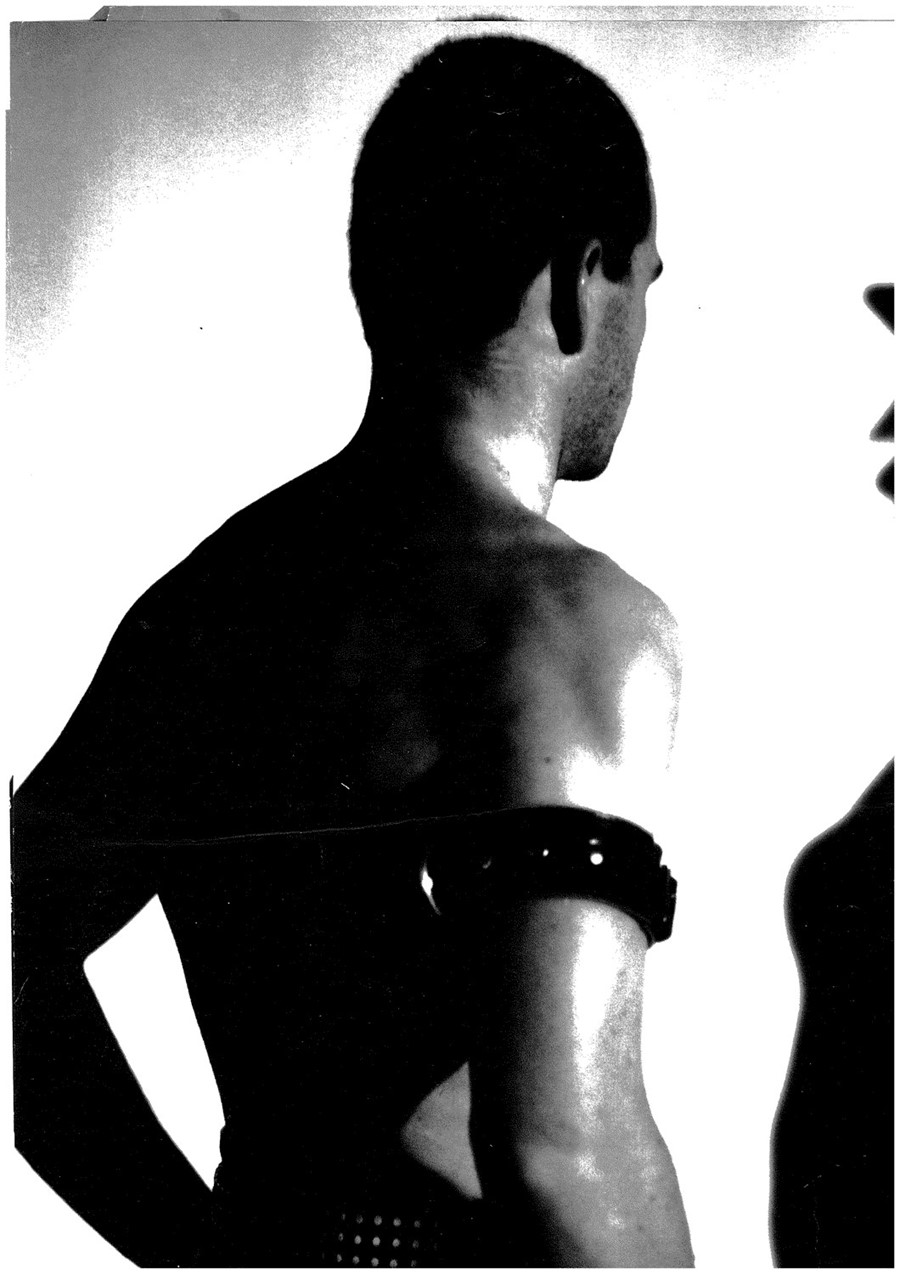

When fetishwear resurged for its second peak a century later, between 1970 and 2000, leather was the material of choice. On the gay scene, an infatuation with leather was alive and well as early as the 1950s. Today, leather fetishwear is worn by leathermen like Max in sex clubs, parties, Pride parades and hook-ups, but some incorporate leather into their everyday lives, too. Common clothes and accessories include leather trousers, boots, jackets, gloves, ties and caps, with harnesses, masks and jockstraps more often worn during sexual encounters.

While leather fetishwear is not exclusively queer, there is a widely acknowledged parallel between the increased visibility of gay and lesbian identities and leather-based fetishes in contemporary culture. Recon – a fetish app for gay and bisexual men – allows leather wearers to connect with others and follow a year-round calendar of global events such as “London Fetish Week” and “Leather Prides” in cities from Los Angeles to Belgium. Paul, a 34-year-old Recon user, tells me that he equates leather with “power, strength and dominance”. He doubts that he could be with someone “vanilla” – a term for someone who doesn’t have any fetishes. “There’s nothing hotter than the feeling of leather on my skin, it’s peak masculinity,” he says. Max, who was first drawn towards leather five years ago, also associates it with manhood. “It’s just so fucking masculine,” he explains. “The more masculine I’ve become over time, the more I’ve been into it. When I wear leathers, it feels like my exterior is reflecting my interior. It’s weighty too: the opposite of something light, diaphanous and feminine.”

“There’s nothing hotter than the feeling of leather on my skin, it’s peak masculinity” – Paul, 34

These remarks reveal leather fetish fashion’s significance to masculine gay identities, particularly those relating to sadomasochistic (S&M) sexual practices. In Hal Fischer’s seminal photography book Gay Semiotics, which analyses coded gay fashion signifiers in 1970s San Francisco, leather accessories like caps were indicators that the wearer was interested in sadomasochistic sex. Lesbians also adopted leather and, nowadays, female sex workers and dominatrixes often wear the material. Though, traditionally, the gay leather scene centres on “dominant” men wishing to “own”, or exert control over, a “submissive” male partner.

Sociologist Meredith G. F. Worthen, author of Sexual Deviance and Society, writes that the leather community first emerged after the Second World War, when military servicemen had difficulty assimilating back into mainstream society. For many of these men, their military service had allowed them to explore homosexual desire for the first time. When the war ended, a void was left by the absence of homosexual sex and same-sex friendships. Instead, many found sanctuary in motorcycle communities where leather clothing was popular. The men who rode these bikes were icons of cultural masculinity, conjuring up an image of dangerous rebelliousness that was alluring to many gay men who were weary of seeing themselves depicted as effeminate pansies. Peter Hennen, author of Faeries, Bears and Leathermen, believes that this caused gay men to “invest in leather with a certain erotic power intimately tied to the way it signalled masculinity.” Queer cultural historian Daniel Harris suggests that the “raw masculinity” that leather evokes “shaped a new form of masculinised gay identity among leathermen.”

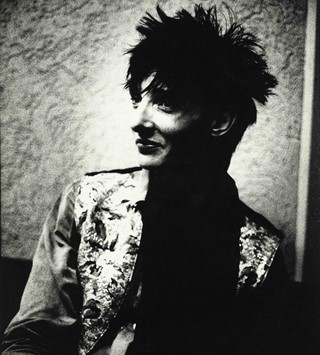

Leather’s military routes, combined with its significance in hierarchy-driven male social groups, are thought to be behind its importance to sexual practices like S&M, which centre on order, discipline and control. Yet outside the leather fetish scene, artist Andy Warhol famously used garments such as the leather jacket as a device to appear more masculine from the 1950s to 1960s. Transforming his personal style, Warhol sought to present a more macho, aloof persona to the heterosexual male-dominated New York art establishment.

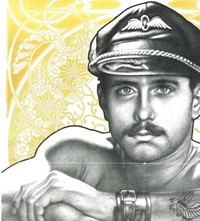

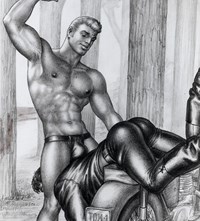

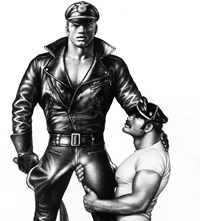

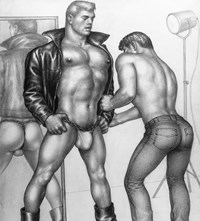

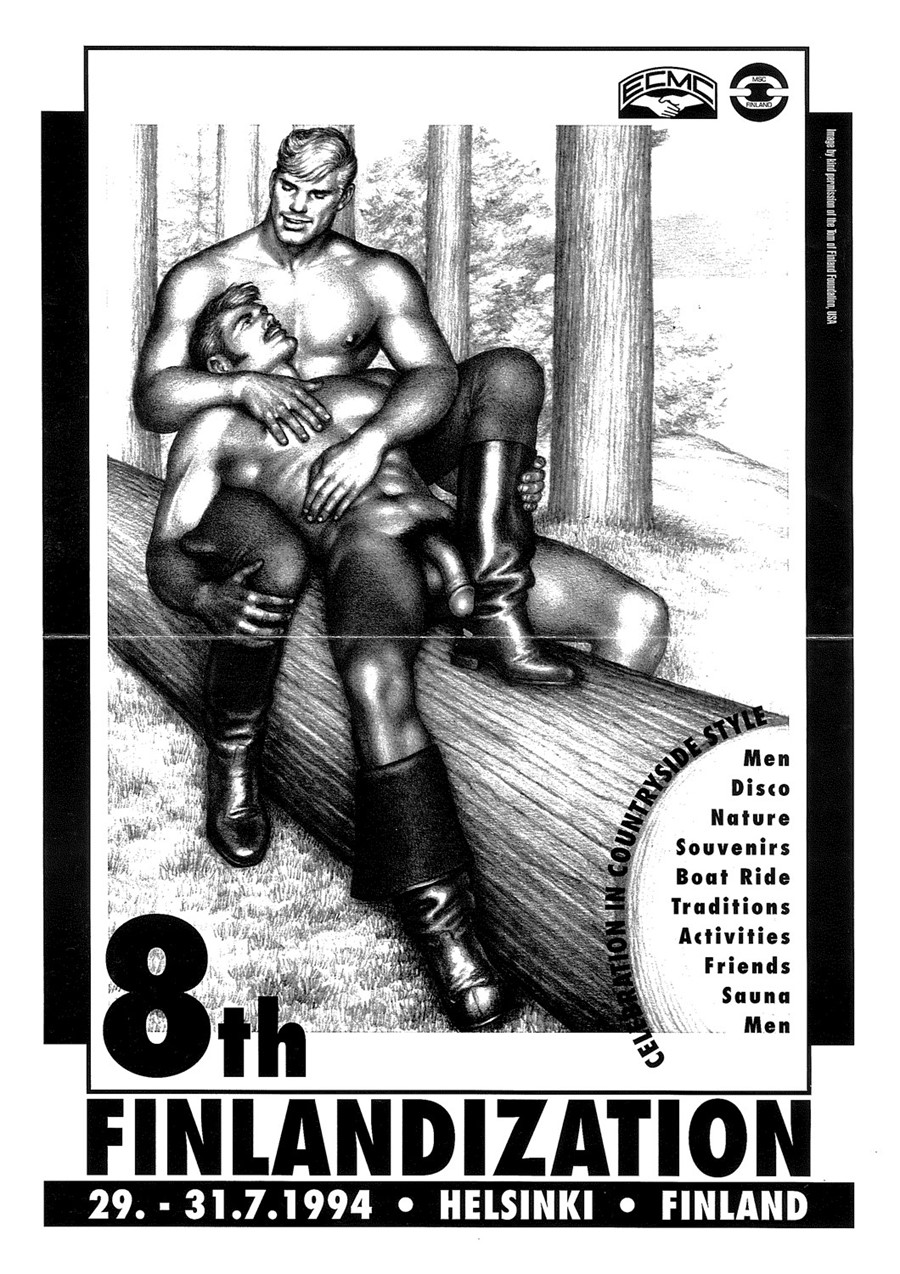

“Tom of Finland ‘set the standard’ for the ‘quintessential leatherman replete with bulging chest, thighs and cock’”

Max tells me that cultural imagery, such as “Tom of Finland, Robert Mapplethorpe, Marlon Brando and James Dean” contributes to his love for leather. Finnish artist Touko Valio Laaksonen, commonly known as Tom of Finland, is behind leather’s signature homoerotic aesthetic. According to feminist studies professor Jennifer Tyburczy, Finland “set the standard” for the “quintessential leatherman replete with bulging chest, thighs and cock.” By depicting working-class men like construction workers, bikers and lumberjacks, Finland allowed gay men to feel masculine and strong while maintaining their interest in those of the same sex. His images are the antithesis of the effeminate gay stereotype that was widely circulated at the time, bringing connotations of hyper-masculinity, strength and, of course, sex to black leather. After being circulated in physique magazines such as Physical Pictorial throughout the 1950s, his work quickly became emblematic of the gay fetish community.

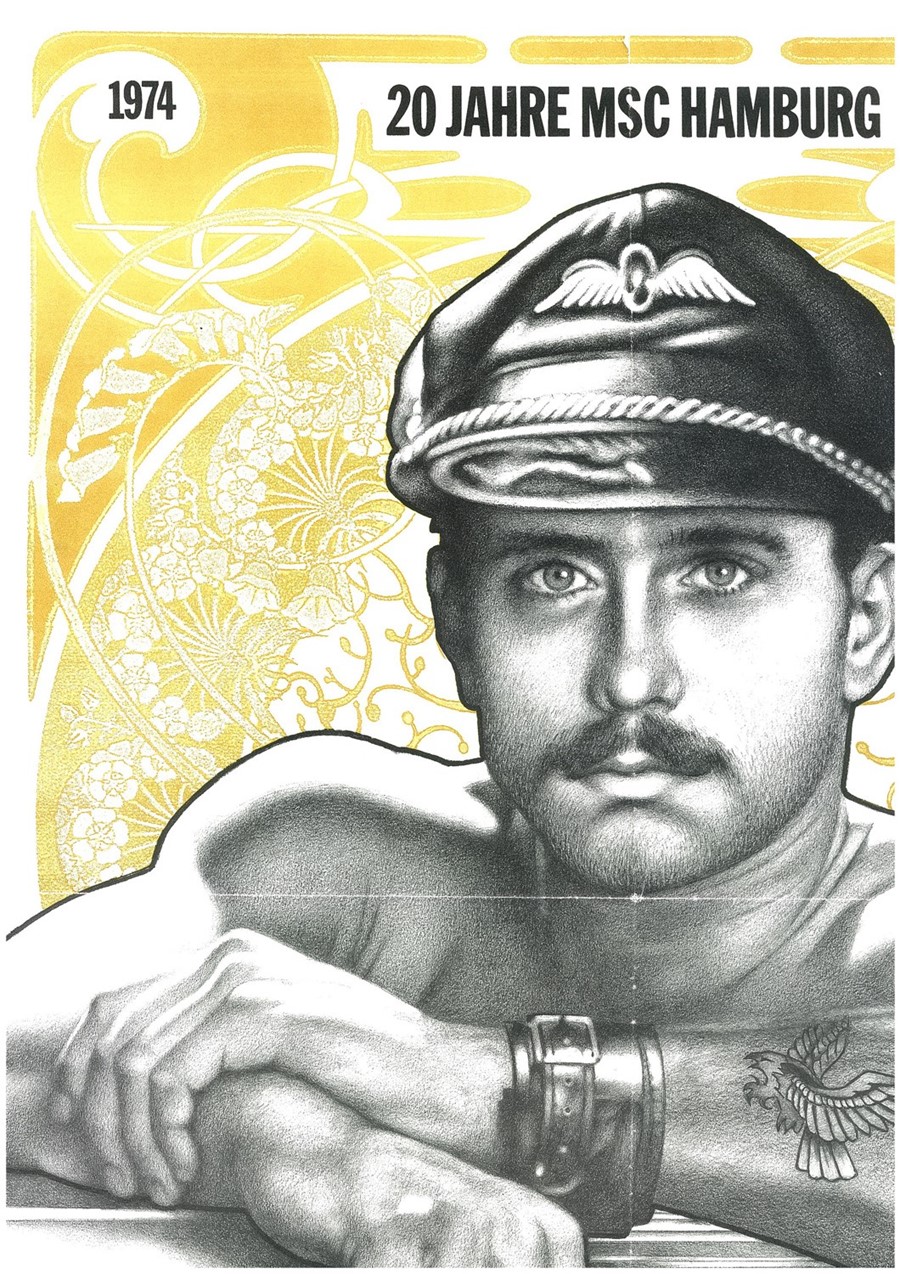

Following the popularity of leather in the queer sanctuary cities on America’s coasts, international travel increased its global appeal, with leather kink scenes developing in London, Berlin, Amsterdam, and parts of Scandinavia. Imitations of Finland’s images became the customary advertisement of fetish events in these places, which were often disguised as motor sport or biking clubs. For the first time, Finland’s reclamation of masculine imagery provided gay men with what communications professor Martti Lahti describes as an “empowering and affirmative” gay image.

Though after years of resurgence, the leather fetish scene is facing challenges. Rising rents and gentrification in the world’s queer-friendly cities have caused most clubs to shut their doors. Fetish apps and websites now mean that attending a leather event is not necessary to connect with leather admirers. Lesbian leather wearers, who have traditionally operated their BDSM club scene separately, have been most harshly impacted by club closures as most gay leather nights purposely ban women from entering. With a full outfit of leathers costing several thousand pounds, it is little wonder that younger kinksters are turning to cheaper alternatives like rubber or sportswear to fulfil their fetish needs.

“Rising rents and gentrification in the world’s queer-friendly cities have caused most clubs to shut their doors. Fetish apps and websites now mean that attending a leather event is not necessary to connect with leather admirers”

The extended rights and freedoms won by queer people in recent decades have also resulted in pressure from wider heterosexual-focussed society to assimilate to their norms. Queer historian Lisa Duggan has described how the pressure to comply with what she calls “neoliberal” aims has resulted in a “depoliticised” and “desexualised” gay identity revolving around “domesticity” and heteronormative institutions like marriage. This gay identity can be exclusionary to those that fall outside its “acceptable” norms.

As the visibility of “vanilla” gayness has extended, heterosexual kink aesthetics have moved further into the mainstream, ushered in by pop moments like Madonna’s Justify My Love, Rhianna’s Disturbia and Christina Aguilera’s Bionic era, plus books such as 50 Shades of Grey. Reality star Kylie Jenner even graced the cover of Interview magazine dressed as a “sex doll”, clad entirely in skin-tight black latex. Though despite figure skater Adam Rippon wearing a leather harness once on the red carpet and the occasional performance costume from Jake Shears, the Village People’s Tom of Finland-inspired outfits and Robert Mapplethorpe’s extremely explicit photographs – both almost 40 years old – remain gay fetish fashion’s most visible representations.

With visible mainstream gay identities remaining “desexualised”, the false link between kink, sexual deviance, immorality and even criminality – a trope peddled for decades to depict gay men as “socially wrong” or “sick” – still lingers, even within the LGBTQ+ community. Andrew Cooper, author of Changing Gay Male Identities, suggests that overt sexuality has become less important to gay identities since the AIDS crisis, when sex – and communities like the leather scene that revolve around sex – became associated with death and shame. In Beneath the Skins, a book that analyses the politics of kink, Ivo Dominguez Jr writes that, as gay identities and attitudes become more sanitised, “leatherphobia” remains a significant barrier. Dominguez suggests that those who practice leather are seen by the wider LGBTQ+ community as “poor relatives they wish to hide” or an “albatross around their public relations neck”.

Yet the leather scene could certainly be more inclusive itself. In addition to its exclusion of women, it is overwhelmingly white. When combined with the fact that elements of the leatherman aesthetic have been co-opted by various sub-fetishes and groups that eroticise white supremacist roleplay and Nazi iconography, this paints a particularly objectionable picture. Then there’s the fact that much of the hyper-masculine culture that surrounds leather promotes the idea that feminine men are inferior. Society’s ever-evolving understanding of the effects of entrenched, socially-constructed gender binaries and toxic masculinity has undoubtedly reduced its appeal further.

However, despite its current challenges, the history of leather fetish fashion is as fascinating as the black cowhide is transformative to those who lust over it. Leather can conjure solidarity among those who feel alienated, while acting as a symbol of sexual liberation. Its history tells a nuanced, important story of just how integral fashion can become to communities and subcultures. To its devotees, it represents more than mere aesthetics or the leather-clad bikers of the past. To them, leather fetish fashion is a way of life.