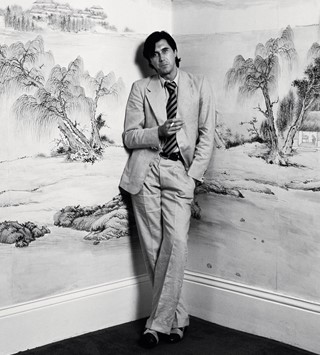

In celebration of Stalker’s re-release, we break down the reasons why Andrei Tarkovsky’s bleak masterpiece is so fondly remembered

Russian directors are famous for using film as a way of nodding to the political situations that confront them. But as time has gone on and the country’s freedom of speech laws have relaxed, these creative social statements have become less subtle. Perhaps that’s why Stalker, a 1979 film by the acclaimed Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky, has spent almost four decades being unduly labeled a work of science fiction. Admittedly, on first inspection it appears to be, but if you scratch beneath the surface, it contains lessons about how people come to terms with a hopeless and heavy reality.

Set in an unnamed country at an unspecified time, the film follows a guide, known as Stalker who is disappointed by the sad state of the world around him and his daughter’s crippling illness. His job is to lead people into ‘The Zone’ – an off-limits area outside of town that, while incredibly dangerous, is said to lead to a place where your deepest desires come true. In an attempt to reach it, he heads into The Zone with a depressed man called The Writer and a curious academic called The Professor, in search of a better life.

What feels like a work of fiction actually winds up reflecting the strenuous search for happiness experienced by those living in Russia during the rise of nuclear power in the 1970s. Rural towns were left to rot, unbeknownst to the people that lived there, as nuclear reactors imploded and silently poisoned them. Tarkovsky’s film makes a bold statement about their plight in a parable-like fashion, proving that reality can often be understood better when viewed through an artist’s lens.

To mark the release of a gorgeous remastered version of the film by Criterion, we decode the reasons why Stalker continues to leave an indelible mark on modern cinema.

It wears the sci-fi label lightly…

Part-dystopian fable and part-social reflection, Stalker certainly isn’t the kind of sci-fi you’d find playing in eye-popping 3D in your local cinema. Instead, it uses the guise of that genre to justify a fantastical premise that runs much deeper.

The journey that Stalker and his two tag-a-longs take into The Zone could be the plot of a multi-million dollar movie, but Tarkovsky’s vision is so bleak and rooted in reality that no Hollywood exec would lay their hands on it. Like a work of neorealist cinema (although we can’t be sure that Tarkovsky would consider it to be), it’s a philosophical film that deconstructs our never-ending search for happiness and satisfaction: two of the simplest and most complicated parts of the human experience.

and has a mesmerising aesthetic…

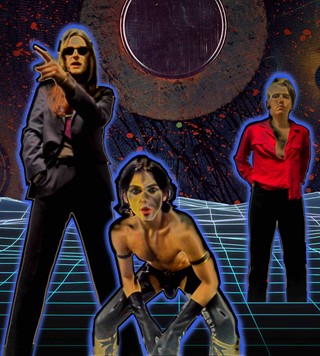

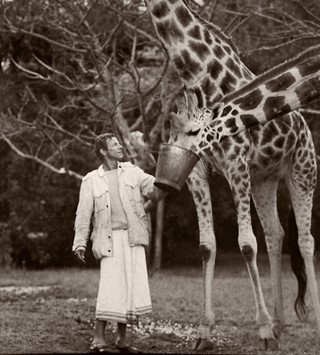

Tarkovsky uses colour the way a painter would. In the film, the world outside of The Zone, in which regular people drag themselves through everyday life, is presented in murky sepia monochrome. It looks displeasing, but even more so once Stalker and his companions have ventured in to their new and undiscovered world.

There, Tarkovsky’s lens gives his characters a newfound clarity. ‘The Zone’ is presented in colour, allowing us to see the men cut through the green, overgrown foliage and clamber through dilapidated shells of former buildings that feel eery and left behind. It’s almost like a run-down paradise, seen as such because it holds more hope for the men than the real world ever has.

The viewers’ patience is rewarded…

Clocking in a few minutes shy of three hours and often moving at a glacial pace, Stalker revels in the idea of making the viewer work hard to experience its enlightening pay-off.

In fact, Stalker’s 163-minute runtime is comprised of just 142 lingering shots. While some last for a minute, others stretch to five and even six minutes of attention-grabbing cinema. It’s worth it, though: Stalker’s often stunning scenery and mind-bending universe will stay with you for a long time after the credits roll.

Tarvosky refused to let others shape it…

Despite being a box office success in Andrei Tarkovsky’s home country, the government-run committee that helped to fund the film criticised the director for making it feel so cumbersome. In retort, Tarkovsky said that the film’s gestative opening scenes needed to be slow, “so that the viewers who walked into the wrong theatre [had] time to leave before the main action starts”.

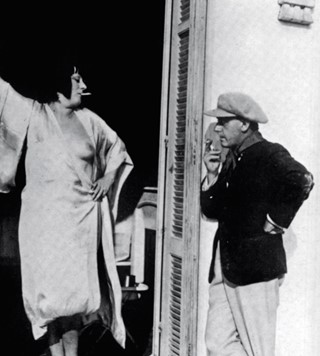

Constantly unsatisfied with certain elements of the film’s visuals, Tarkovsky became known for regularly firing cinematographers and crew members, reshooting the film twice before settling on the cut he felt the most content with. One watch of Stalker in all of its barren, stripped-back glory will prove that he was a perfectionist; an auteur with a vision that he was hellbent on fulfilling.

and it’s the film that he ultimately died for…

The vast majority of Stalker was shot in Tallinn, Estonia inside a number of abandoned power plants in order to replicate the desolate nature of The Zone. But it’s while the cast and crew were here that they were exposed to some of the same horrifying chemicals that influenced the film in the first place.

A still functioning chemical plant upstream was leaking poisonous liquids into the river. The film’s sound designer Vladimir Sharun believes it was an exposure to this that has led a huge proportion of Stalker’s crew to die shortly after the film’s release. Andrei Tarkovsky himself died of throat cancer on December 29th 1986. Coincidentally, in a scene from inside The Zone, a calendar card with the date December 28th can be seen floating in a vat of water; the last day that this legendary and influential director lived.

Stalker is released on Blu-ray by Criterion on July 24th.