Steve McQueen’s Tate Modern exhibition – his first major exhibition in the UK for 20 years – proves him to be one of Britain’s greatest living visual artists

- TextPeter Yeung

Gloom and darkness descend after the first few steps into Steve McQueen’s epic survey at London’s Tate Modern: the gnawing sound of helicopter blades clashes with a mysterious language being chanted and the room is near-black but for two dim projections (even the windows by the entrance to the Blavatnik Building exhibition are blacked out). The space is said to have been designed by McQueen to feel like a gay cruising spot – seedy, uncertain, volatile.

Although it might seem strange, this is also something of a step into the unknown for the 50-year-old. Despite winning the Turner Prize, the highest award given to a British visual artist, back in 1999, and after a series of critically lauded films and claiming the Oscar for Best Picture in 2014 (the first black director to ever do so) with 12 Years a Slave, this is the first major exhibition of McQueen’s artwork in the UK for two decades. He’s the only artist in history to take both accolades.

McQueen himself, born on a tough west London estate, has called it a “homecoming”. On the evidence of this exhibition, which features 14 major works spanning film, photography and sculpture, he has been criminally underrated on these shores. It makes a persuasive argument that he is Britain’s greatest living visual artist – and how the country needs his brilliant, questioning mind.

Yet the questions that McQueen raises are painful ones, dealing with narratives around life and death, human experience and moral responsibility. Quite literally reaching the depths of the world, Western Deep (2002) follows the hellish lives of South African workers at the world’s deepest gold mine. It employs more than 5,000 people, operates 24 hours a day and requires these black labourers to descend three-and-a-half kilometres to reach it. Silent, almost meditative images of their descent are violently juxtaposed with bone-rattling, volume-at-11 clips of the industrial machinery.

It’s these subterranean realities that McQueen is constantly gnawing at. But what makes him unique is how he distills these issues until they are almost abstract, utterly potent. In Static (2009), the Statue of Liberty is filmed from a helicopter after the 9/11 attacks, circling round and round incessantly. But close-ups show this icon of liberty, the welcoming point for those who enter America, is covered in bird shit and the old lady’s copper surface has rusted and oxidised.

It stands as a companion video with Once Upon A Time (2002), a sequence of images that were originally selected by NASA in 1977 to represent life on Earth, sent along with the Voyager I and II missions. It’s quite the utopian experience – lovely colourful photos of gardens, diagrams of the body – but the creators somehow neglected to mention our planet’s war, disease and rampant inequality.

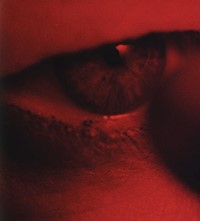

There is serious breadth on show. Right from his first film, Exodus (1992/97), where he pursued a pair of elderly black men carrying palm trees through east London with his Super 8 camera, deftly speaking on migration and identity, to Charlotte (2004), an almost Surrealist, scarlet-coloured short where he pokes actor Charlotte Rampling in the eye, and the sculpture Weight (2016), a gold-plated mosquito net draped over a prison bed-frame, alluding to interplay of protection and confinement.

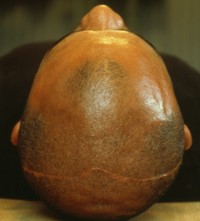

McQueen’s more experimental uses of sound and image make for the most memorable work. None more so than in 7th Nov. (2001), a single back-lit photograph with a soundtrack, named for the date McQueen’s cousin Marcus accidentally shot his brother. That event and its aftermath are intimately recounted by Marcus, who at one point describes “a four-foot jet of blood coming out of his head like a hose” in his lilting London accent. All the while, a still image of the brother’s lifeless head draws the eye – to his protruding ears and nose and along the scar that bisects the top of his skull. In its raw simplicity, it leaves you staggered.

That must surely be the goal for any artist. But McQueen is doing it while addressing complex and essential problems like racism, violence, oppression – as well as sadness. “One of the most challenging and extraordinary artists of our time” is how Tate Modern director Frances Morris described him at the opening. And one that is acutely aware of his own powers.

McQueen first visited the Tate aged eight, where he learnt “anything is possible”, and his concurrent show at Tate Britain – filled with specifically commissioned photographs of more than 70,000 London students in Year 3 – is clearly aimed at passing on that lesson. We should all be taking notes.

Steve McQueen is at Tate Modern, London, February 13 to May 11, 2020.