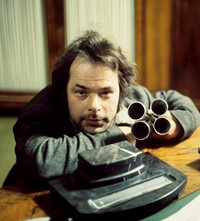

Werner Herzog: “My Films Are Not Art”

Michael-Oliver Harding speaks with the cult Bavarian filmmaker about the fall of the Berlin Wall, his bent for playing villains and his riveting new documentary, Meeting Gorbachev

The evening of November 9, 1989 will forever be known as the night the Berlin Wall – the ultimate symbol of the Cold War – came tumbling down. 30 years ago this week, East Germans swarmed the many checkpoints between East and West Berlin, walking past overwhelmed border guards and into the arms of elated Wessi (West Germans), who greeted them with flowers and champagne. At the time, Werner Herzog was working in the remote mountains of Patagonia.

“A soundman with a short-wave radio told me that the Berlin Wall had come down a few days earlier, and I immediately stopped shooting,” recalls the legendary German cineaste, when I ring up his home in southern California. “I thought: this is so big! I was immediately overcome with a feeling of joy that has never left me.”

Herzog, who’d travelled on foot around Germany’s border five years earlier because “only poets could provide unity”, eagerly points out that this pivotal geopolitical event was not spearheaded by the political class. It was truly the will of the people. “As you’ll remember, Margaret Thatcher was vehemently opposed to it – as were Mitterand, the US and Germany’s social democrats,” he says. “Intellectuals like Nobel Laureate Günter Grass didn’t like it either – and I still dislike him with all my heart today.”

Against all odds is also how many would qualify what Mikhail Gorbachev, the eighth and final leader of the Soviet Union, accomplished while in office. The USSR’s rapprochements with the West on a number of fronts – from its negotiations with the US to reduce nuclear weapons to relinquishing control of Eastern Europe and the GDR – were beyond unexpected, as Herzog and co-director André Singer explore in their fascinating new documentary Meeting Gorbachev, based on a wealth of archival material and three extended sit-downs with the ailing 88-year-old statesman.

German reunification is also what brought the cult Bavarian filmmaker to this project. Herzog makes no attempt to conceal his affection for a man who’s difficult to pin down: often revered in the West, but whom many of his own blame for the dissolution of the Soviet Union. “Gorbachev and I had similar upbringings,” explains Herzog, “growing up hungry after the war in very remote areas with no running water. We also both travelled on foot early on. Gorbachev knew about this, which made for a very easy, almost instant rapport.”

Methods in Madness

Perhaps that’s why Herzog, a notoriously intense interviewer, determined he could break the ice with this heavyweight of world history as follows: “I am a German, and the first German you met probably wanted to kill you.” The unorthodox approach doesn’t backfire, with Gorbachev immediately launching into fond recollections of the kind Germans near his hometown who’d make wonderful biscuits in the shape of rabbits. By all accounts, a quintessentially Herzogian moment.

The self-taught filmmaker has a stellar track record of offbeat methods to his madness: hypnotising an entire cast of actors, hauling a steamship over a mountain in the Peruvian jungle, publicly threatening to kill his lead actor during a shoot and travelling to an evacuated island faced with an imminent volcanic eruption. And afforded 45 minutes to interview a death-row inmate for Into The Abyss, he chose a similarly blunt (and fruitful) opener: “The fact that your childhood wasn’t good doesn’t exonerate you,” he warns the prisoner, who minutes later shares alligator and monkey stories with Herzog. “It does not necessarily mean that I have to like you.”

When the tables are turned and Herzog is the one fielding the questions, he has been known to dish out equally frank assessments to those who take unwelcome detours. When asked to comment on certain geopolitical tensions, he recently told The Guardian: “I’m not a pundit, don’t push me into that corner.” As to why he hadn’t included certain historical events in Meeting Gorbachev, he told a TIFF Q&A attendee: “I’m not a historian, I’m a poet.” On this day, Herzog proves to be a kind and generous raconteur. He only takes issue with my use of the term ‘artist’. “I have never created a piece of art,” rectifies Herzog. “My films are not art. They’re something else. I don’t exactly know what. People always say: ‘you are an artist’ but no! That doesn’t feel right. I’m much more like a soldier.”

A Soldier of Cinema on a Mission

Meeting Gorbachev finds this soldier on a subversive mission: to remind the West there is value in international co-operation, and that he considers the demonisation of Russia a major mistake. “The media distortion is almost an exclusive narrative in the West,” he argues. “You find it everywhere, and I think we should rethink our position vis-à-vis Russia. Vladimir Putin does not want to re-establish the Soviet Union. That’s one of the distortions in Western media. Russia seems to be a stable entity compared with other unpredictable forces. And this documentary is a reminder that the unthinkable – which went against conventional wisdom at the time – is possible. Just look at Gorbachev and Reagan.”

Indeed, Gorbachev’s establishment of a cordial relationship with the American leader in the 1980s marked a turning point in the Cold War, especially for nuclear arms reduction. Without commenting on current geopolitical tensions, Gorbachev nevertheless tells Herzog that “people who don’t understand the importance of co-operation and disarmament should quit politics”. The 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster obviously pressed forward his campaign to reduce weapons, but Herzog adds that it also confirmed to him that the system was no longer functioning. “The highest leader of the country was not even informed at first, and then the president of the Academy of Sciences [of the Soviet Union] only told him: ‘ah, that’s a minor thing – you drink a few vodkas and you sleep it off.’ That was the attitude and organisational response. The warning of the population did not happen at first. Gorbachev saw that there had to be something fundamentally changed.”

Heroes of a Herzogian Kind

But coupled with major food shortages and excruciating economic woes, the Chernobyl event became a symbol for the Communist bloc’s waning days. Gorbachev would not fulfil his promises of fundamental reform to improve his countrymen’s lives. Which makes him a tragic, underheralded hero cast in the classically Herzogian mould – an idealist with a beautiful vision who fails on an epic scale. Think of Grizzly Man’s protagonist Timothy Treadwell, another Herzog doc about a passionate environmentalist who lived among wild bears in Alaska until one of them fatally attacked and ate him. When I ask Herzog about another politician he deeply admires, tragedy is once again a huge part of the appeal. “I have to go far back in time to Roman Antiquity to Fabius Maximus, surnamed Cunctator (or ‘the delayer’ in Latin), in power during the Second Punic War. He’s the one who brought down [Carthaginian general] Hannibal by avoiding open-field battle after the most catastrophic defeat that Rome had ever suffered. Until now, he’s derided in history as a cowardly, hesitant one. But he’s the one who saved the Occident.”

When Herzog asks Gorbachev about what we might read on his epitaph, the former commander simply answers: “we tried”. “When you look at the general population in Russia today, there is a good portion of people who believe him to be a traitor – giving up the Soviet Union,” Herzog estimates. “I was in Moscow a little over a year ago and I had the feeling that the mood was changing. The film showed there not long ago and had a huge, warm response for Gorbachev. I think people are starting to understand that the real catastrophe came from Yeltsin.”

For decades now, Herzog has been winning over legions of fans with his beloved Teutonic drone, his wildly philosophical ruminations and his hilarious takes delivered with stone-cold sobriety. He’s declared a Holy War on TV talk shows, taught a film class entitled ‘The Neutralisation of Bureaucracy’, referred to cinema vérité documentarians as accountants and storyboards as the instrument of cowards. He’s also, at times, relished the opportunity to portray bona fide on-screen villains that tap into what some might read as a menacing presence: a domineering father in Harmony Korine’s Julien Donkey-Boy, a former Soviet political prisoner in the Tom Cruise action thriller Jack Reacher and someone to be feared in the forthcoming Star Wars television series The Mandalorian, with his sinister character stealing the spotlight in a teaser trailer when he asks: “Bounty hunting is a complicated profession. Don’t you agree?”

“It’s verifiable,” Herzog sums up to explain why artists such as The Mandalorian showrunner Jon Favreau associate him with such darkness. “You see me on screen and I’m frightening. And I was paid handsomely. But of course, as a private person, I’m not like that. My wife will actually tell you that I’m a fluffy husband. But it’s a persona, a stylisation. I don’t think I’d be any good as a mild-mannered grandfather who presides over a happy family. I wouldn’t be credible. And it would be awful.”

Meeting Gorbachev will screen in cinemas nationwide from November 8, 2019.