“I would like to think that this series of works asks what the human project is, and maybe give us a few pointers to another way of being,” the British sculptor tells Harry Seymour

- TextHarry Seymour

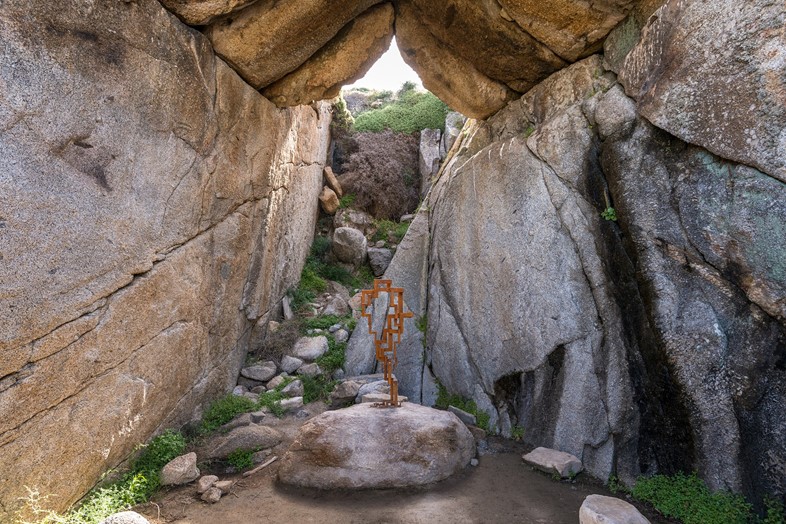

With a new summer exhibition, the British sculptor Antony Gormley has repopulated the ancient ruins of the uninhabited Greek island of Delos with 29 of his bodyforms – and become probably the first artist in almost two millennia to make a work of art for the site. Harry Seymour sat down with him to discuss how the show came together.

Harry Seymour: What was the selection process for works in the show?

Antony Gormley: I came to the island and like a sniffer dog went around thinking about what sites would be appropriate for what works. We thought we ought to have enough works for the archaeologists to refuse some of them, because we thought that there would be contention. In the end, they didn’t refuse any, so that was brilliant.

HS: What is the relationship between your work and the ancient sculptures on the island?

AG: I think that the Archaic korai sculptures are the pieces I feel closest to. Korai means young man, so they’re anonymous to that extent. They have one foot in front of the other, but they’re about the potential to move rather the description of movement, which is critical. There is something very touching about how still they are, and in a way, how crude they are. I think my work is quite crude, and on the whole pretty clumsy in its attempts to bear witness to the human space in space.

HS: So is your work the archaeology of the future?

AG: It is, but that suggests I don’t have any hope for it in the present, which I do, even though it’s taken an enormously long time for people to think that these aren’t just some crappy kind of surrogate statues. I would say they are instruments through which the future might be made, or reconsidered. I would like to think that this series of works asks what the human project is, and maybe give us a few pointers to another way of being. I think we’re at a crossroads situation – and it is becoming more urgent – the fact that there are ten billion of us, we can’t go on desperately trying to get as much as we can in the fear that tomorrow there won’t be enough.

HS: Because the sculptures are manipulated moulds or scans of your body, do you feel like you inhabit each work?

AG: I don’t think of them as me, but some are relatively indexical registrations. I start with the proposition, why make a second body when you have one already, and why make a body from the outside, when you can work on the one you already have from the inside? I don’t think of them as portraits, but more memorialised shadows, or industrially made fossils of a particular human existence. I can’t deny there is an element of narcissism in the whole project anyway, which is ‘oh here is something that I’ve made that I want to share with and want to be everybody’s’. I want this particular bit of my experience to somehow be accepted as universal. That may be hubris, and unlikely.

HS: Do you feel like you share a sense of ‘contemporary’ with these ancient artists?

AG: There are the ancient remains of feet of about seven sculptures that were all the benefactors of altars on the island. Those are, in continuation of your last question, self-congratulatory images. My works aren’t up on plinths or overlooking sanctuaries that I’ve paid for. I think the ancient sculptures here are amazing, such as the lions, which are so strange and feel as though they have been made by people more conversant with lizards than lions.

HS: Here, unlike in a museum, I noticed people have an urge to touch your works, how do you feel about that?

AG: I have played on it a lot. There are ones you can touch, and others on the skyline that you see but you’re never going to get to. Some you’re invited up to join. The whole way that I have treated the site is to play with the way that sculptures can be revealed within the remains – the idea of the hidden and revealed, the remembered versus the seen, versus the touched.

HS: That sounds like the way a visitor would approach an archaeological site rather than a gallery?

AG: Yes that’s what I like about archaeology; there are a few clues and you have to do a lot of work to re-inhabit, and think about all of the life that filled Delos. 35,000 permanent inhabitants once, with Syrians living in one area, Italians around the port, Jews making silverware, and one of the first synagogues ever founded. I mean there isn’t much of it left to see...

HS: And how was it working with the archaeologists from the Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades?

AG: Well it looks effortless, doesn’t it, the whole thing. Truth is, each work had to be very securely fixed down to stop it falling over and killing someone. My team of between six and ten people were here from January, and the archaeologists gave them absolute hell. They weren’t allowed to do anything that would compromise ancient surfaces – which I am thrilled about. The Ephorate have been very generous you see, because traditionally they’re the defender of the Ancient Greek identity, against tourism and development. But you can see here they are really arguing for people to recognise cultural continuity and actually not be so fixated on ‘oh the past is the best that we can ever do’ or ‘the past is the only place that we can find pride in our identity that gives us hope’. That change is possible, but anyway, it could go either way...

HS: That sounds ambitious.

AG: It is just a whisper, isn’t it. It’s not trying to occupy or colonise or dominate – I mean we couldn’t anyway. These ruins are the work of 1,000 years and thousands of slaves, and that idea that you could take it on in any sort of occupational way is just ridiculous. So all my work could be is this sort of... I think acupuncture is the best word for it.

SIGHT: Antony Gormley on the Island of Delos has been organised by the Greek non-profit arts organisation NEON, in conjunction with the Ephorate of Antiquities of the Cyclades, and is open until October 31, 2019. The best way to reach Delos is by taking a short boat ride from Mykonos.