Speaking to Dominique Sisley, the artist, writer and musician discusses her new album, the state of contemporary art and why it’s time for a revolution

- TextDominique Sisley

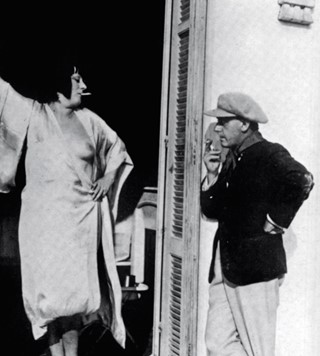

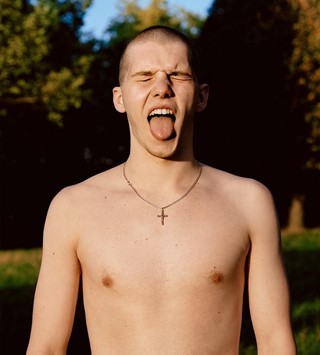

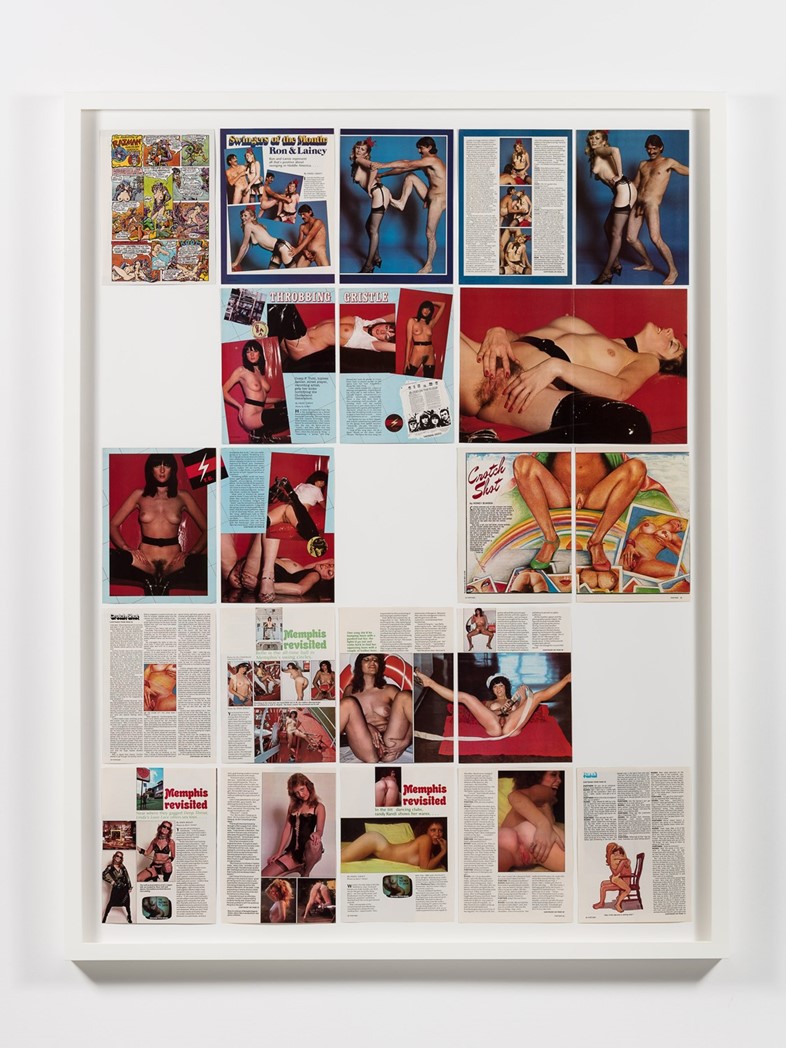

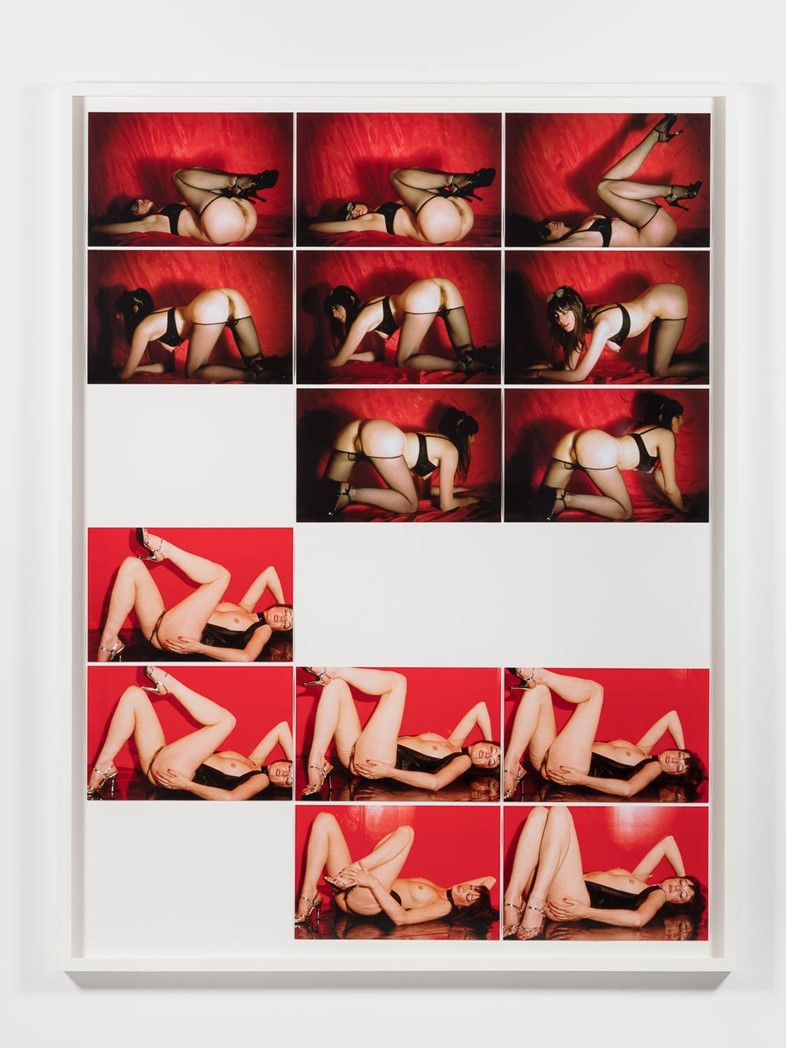

Cosey Fanni Tutti has crammed a lot of lives into her 67 years. An artist, writer, musician and pornographic model, her work has always been about questioning the nature – and limitations – of creative self-expression. In the 1970s, this meant putting on explicit performances with the avant-garde art collective COUM Transmissions, which often included a blend of used tampons, live sex and bodily fluids. The Hull-born artist was also part of Throbbing Gristle, a pioneering industrial noise band she founded with fellow COUM member, and then-partner, Genesis P-Orridge.

These days, Tutti is living a calmer, more reflective life in the idylls of the Norfolk countryside. While no longer lubing up dildos with blood, she is still fully immersed in the creative world; releasing her first solo album in over three decades, TUTTI, earlier this year, and appearing in a new group art exhibition, Straying From The Line, at Berlin’s Schinkel Pavillon. We caught up with her to talk porn, the internet, and starting a revolution.

Dominique Sisley: You’ve had a reflective few years. In 2017 you released your autobiography, Art Sex Music, and this year you released an album which you describe as “expressing the totality of your being”. Why now?

Cosey Fanni Tutti: I just happened to be in a place where I was ready to write about my life. People were asking me when I was going to write my autobiography, which had never even occurred to me. But then things happen: you start losing really close friends, and you want to put forward your life as it happened. No matter what anyone else writes about you, this is you.

DS: Was it cathartic to write?

CFT: No! A lot of people ask me that, and it wasn’t the word I used. I got sad – I’d come across things and think, ‘oh I didn’t need to do that did I?’– but it wasn’t cathartic. My work has always been about what I do in my life, so I’m almost getting things off my chest as I go along.

DS: Your work has always centred around sexuality – do you worry about how our attitudes have changed towards sex over the years? Or do you think we’re opening up?

CFT: I’ve worried about it all my life, that’s why I’ve worked with it so much. Sex is always a problem for someone; always a subject for control. I find it very odd that we have so much celebration of diversity, sexuality and gender at the same time as we have such a storm of protest about it. You see Gay Pride take over the streets, and then there are all these porn sites being shut down.

I think it’s got better in terms of diversity and what’s available, and the fact that there are female porn companies and production companies. I think that’s great. There’s a great variety of pornography available in that respect, so the market did open up before people tried to close it down again.

DS: You made allegations of abuse against Throbbing Gristle bandmate Genesis P-Orridge in your book. How do you feel about that now that the dust has settled? Is it something you want to distance yourself from?

CFT: It’s part of my history. On the one hand you think, ‘please don’t give the spotlight to someone who has behaved so badly’. Because everyone that’s been in that situation gets on with life and leaves it behind. [The abuser] is not important – your life is important, not theirs.

But on the other hand, you don’t want to hide it. You shouldn’t hide it. I wanted to be honest. That’s the dilemma: you all of a sudden are making people more important again, when the whole point of the abuse was that you were lesser-than. [But] you also want to expose it, because it carries on, you’re not the last one in line. I got letters and emails from people talking about their experiences with Gen, which gave me a different perspective – things I never knew about. [The allegations] opened a can of worms for a lot of people. Someone said, ‘do you think that you allowed people to speak about what happened to them as well?’ And I suppose I did – I must have done, because they did.

DS: So it helped to validate other people’s experiences.

CFT: Yeah, making them feel like they’re not the only one. They’re not going mad. It’s very hard to accept when you thought you loved someone and they loved you, that that’s not what it was at all. It’s a huge betrayal. But happily I’ve had an amazing life since then.

DS: Much of your work in the 1970s was seen as controversial and transgressive. How do you think it would have fared in the internet age? Would it be harder to shock now?

CFT: I think the fact that [art] is accessed through a muted channel, the internet, means that the experience isn’t that personal or powerful anymore. I think the shock value is still possible, but only when it’s one-to-one, which is a pre-internet experience for most people. You can read about it, but unless you’ve been there and experienced something very similar, you’ve no idea what it’s like. It’s like falling in love or motherhood – until you’ve experienced it, you don’t have a full understanding of it.

DS: Do you think it’s harder to feel truly moved by art now, because of that?

CFT: There’s a willingness to connect which is being lost, and that’s the biggest problem. With the internet, you’re allowed to be at a safe distance from things – this is just my theory, it could be totally wrong, shoot me down in flames if I am.

I can’t look at some things on the internet, and I wonder why they’re even there. War footage, news coverage – I don’t need to see those things. I know they’re going on, and I do what I can to do anything about it. But I don’t need to see it all the time like that. I get the sense that it’s a competition between what’s the most shocking footage that you can get away with showing, and how invasive into someone’s privacy and grief can you get. I find that totally obscene…

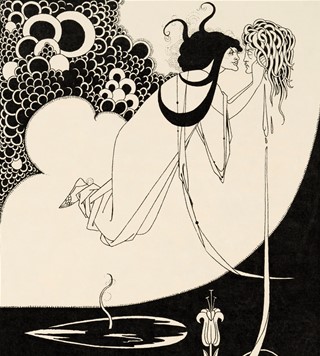

DS: So how does that work with art? When does provocative or challenging work become obscene?

CFT: For me, I think I can sense it. I don’t know why. I think art can be genuinely provocative to help move things on, or it can just be provocative for the sake of it, because it will shock and help someone’s career. It can be a promotional tool for some people.

I think work can be informational about something negative, but still be open enough to suggest that this is something we can change: to point out that this should not be happening. But there has to be that light of positivity in works of art.

DS: You’ve always managed to remain incredibly independent throughout your career. Do you think it’s harder to stay that way now, given the growing interference of big brands and advertisers? Is it something we should worry about?

CFT: It’s worried me since the 80s, because that’s when it started. Everything – music, art, even fetishism – was being co-opted by advertisers. The turnaround of that is so fast now because of the internet, so they see everything on there really quick and they grab it. It’s assimilated and put into an ad.

That’s what’s quite worrying in terms of your artistic creativity: once you put it out there you know you’ve lost it. It’s going to be co-opted, corrupted and used commercially. You’re just a source of ideas for industry, and that’s not why you’re doing it. We’ve always created our own stuff, and people have said to us in the past, ‘if you did your music for this, you’d be rolling in it!’ But that’s not why I’m doing it. I can’t even think of doing something like that.

It’s also soul destroying for people when their work is assimilated so quickly – it makes you think ‘why bother?’ I think that’s really sad because you have to bother, because those people that are taking it, they can’t do it on their own, they come to you. So you have a gift that you should cherish and not try to give up just because of someone else’s ruthlessness.

DS: Do you think it’s time for a revolution?

CFT: Wouldn’t it be great? I’ve been waiting for 20 years! Is anyone brave enough? It’s got to the point now where you have younger people now actually coming out and doing something, and I think that’s wonderful. That’s the connection with the real world again. You can sit in virtual reality for a long time, and then all of a sudden the markets crash or the satellite goes down and you haven’t got it. It’s that moment of realisation which essentially has to come. And with it, something positive comes, hopefully – a great life in the real world, with each other.

Cosey Fanni Tutti’s new album TUTTI is out now.