A Rare Interview with Pablo Picasso’s Son, Claude

- TextDaisy Woodward

Speaking to Another Man, the son of one of the greatest artists of the 20th century opens up about his relationship with his father, his memories of Matisse and the moment Picasso ‘found Picasso’

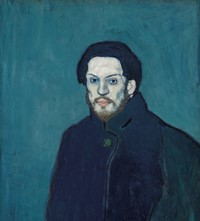

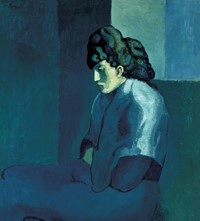

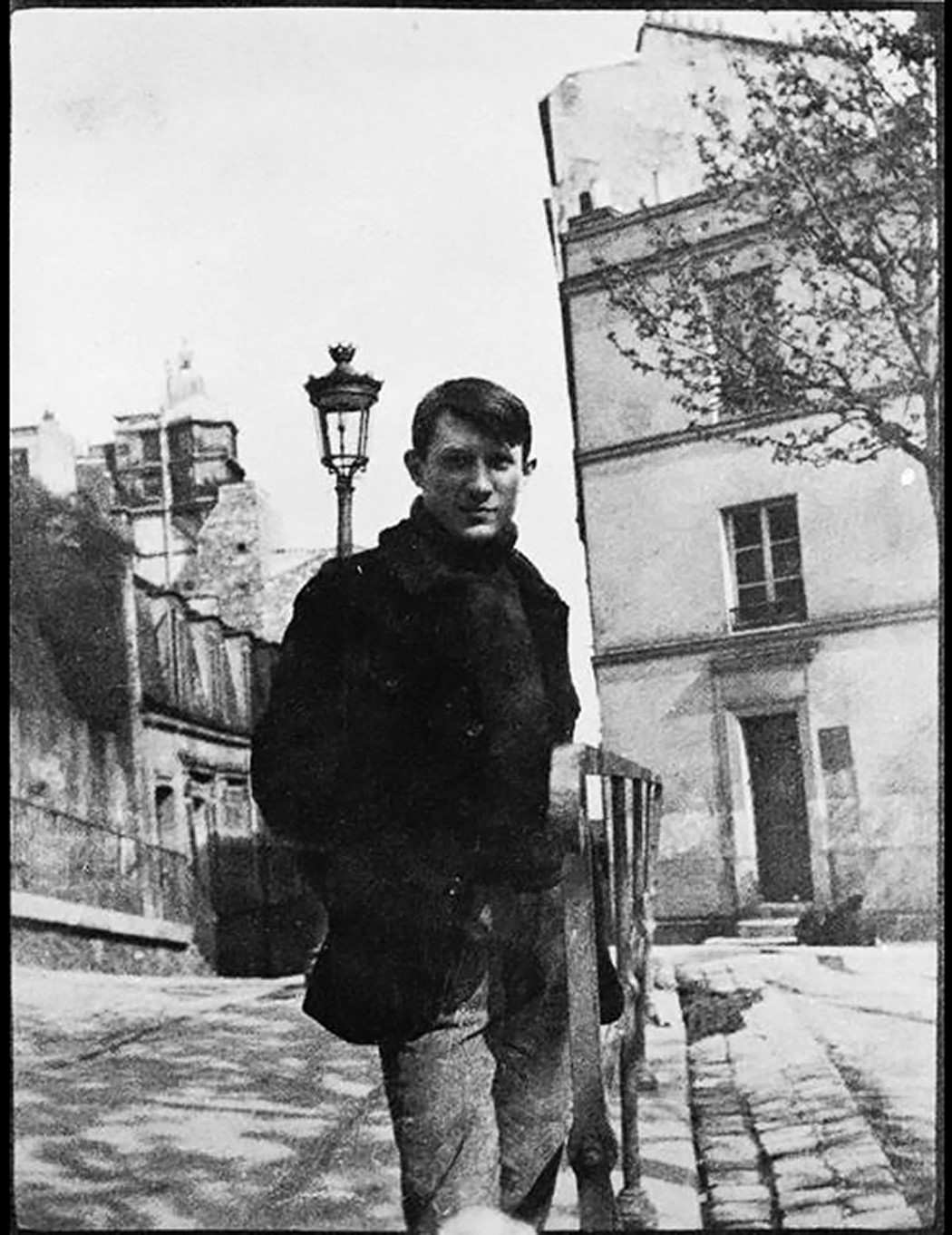

“I was a painter and became Picasso,” Pablo Picasso famously declared, as recounted by his muse and former lover François Gilot in her 1964 memoirs, Life with Picasso. And while it is possible in the case of most great artists to trace a path from fledgling experimentation to fully realised mode of artistic expression, Picasso’s trajectory from painter to icon is particularly remarkable to observe – occurring as it did within a concise six-year period, between 1901 and 1906. It is this time frame, spanning the artist’s renowned Blue and Rose Periods, that is the focus of the Fondation Beyeler’s current exhibition, The Young Picasso – Blue and Rose Periods, now entering its final month.

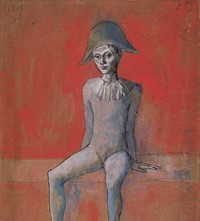

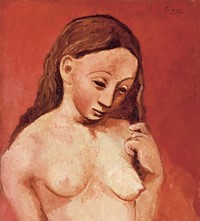

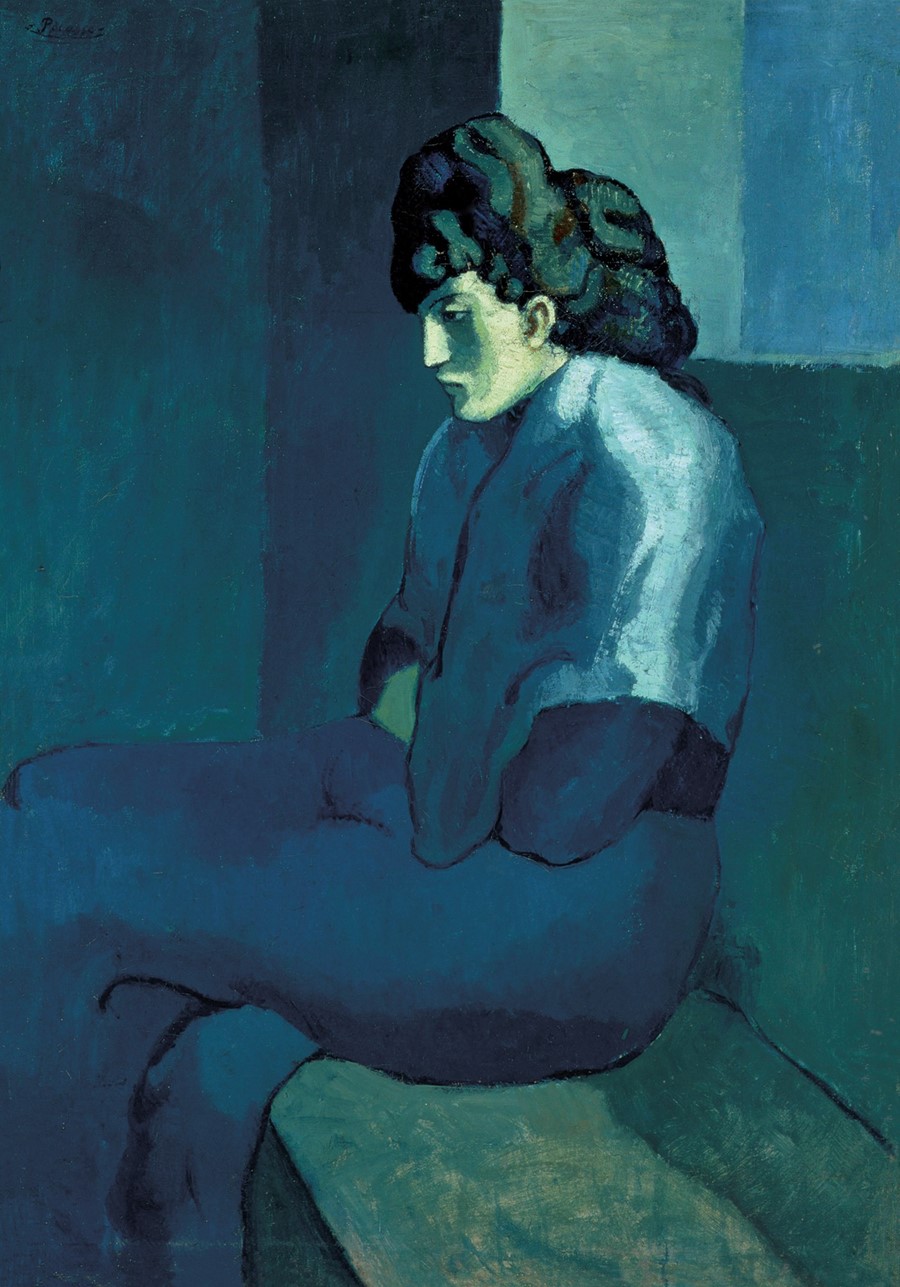

A stunning selection of around 75 figurative paintings and sculptures, displayed chronologically in the naturally lit Basel museum, plunges us into the world of the 20-year-old Picasso as he arrives in Paris in search of new themes and forms within his work. The Blue Period sees the artist refine his palette to just a few bleak aquatic colours, reflecting the artist’s own melancholia after the death of his close friend Carlos Casagemas, as well as the psychological suffering he witnessed among the marginalised classes while living between Paris and Barcelona. In 1905, he shifts gear, and colour, working in softer pinks, ambers and ochres to “confer the dignity of art on the hopes and yearnings of circus performers,” the exhibition text informs us.

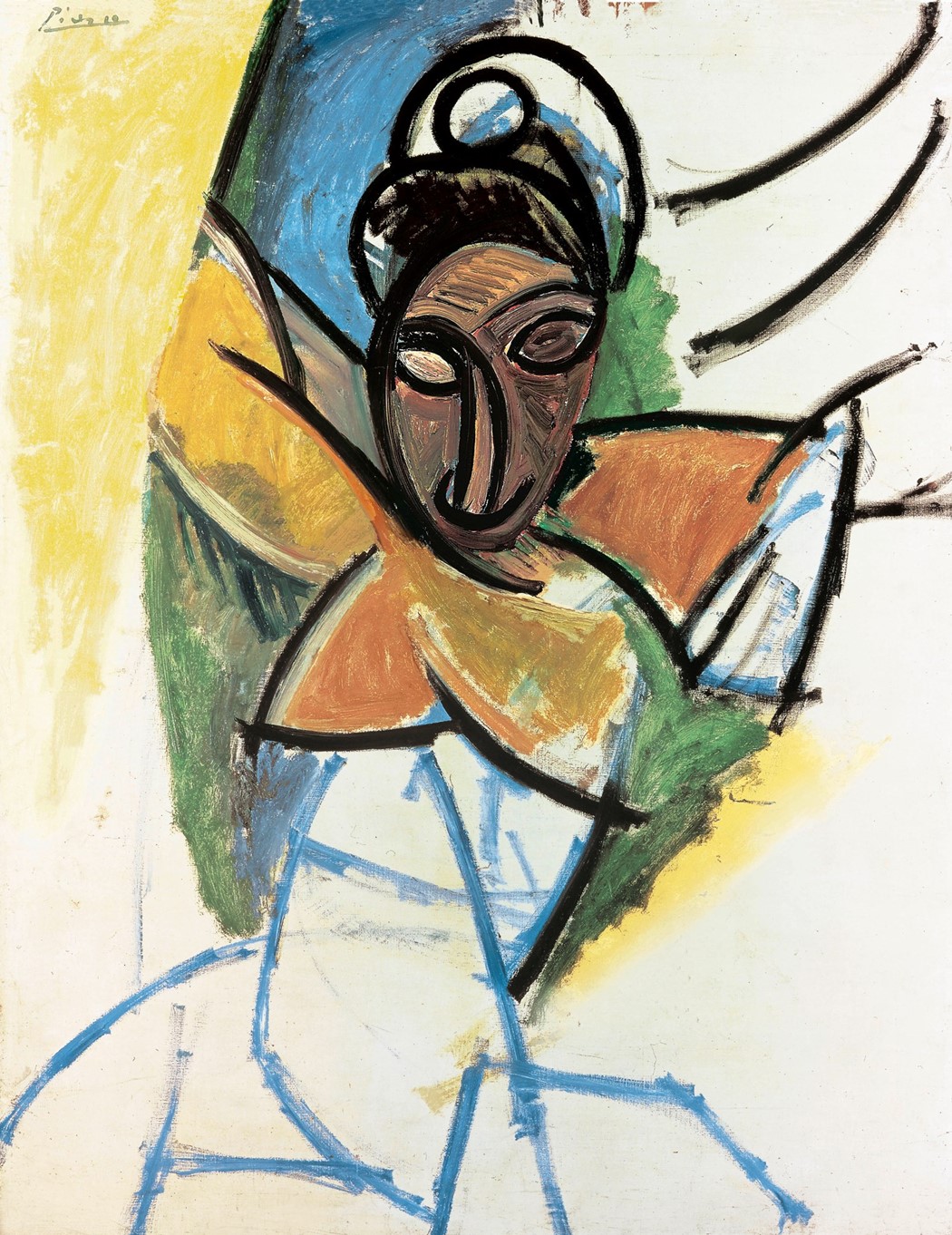

These deeply affecting works are not only poignant musings on life’s most existential themes, from love and yearning to loneliness and death, but also paved the way for the epochal emergence of Cubism in Picasso’s work, which occurred in 1906 during a trip to the Spanish Pyrenees. While there, the artist began experimenting with the increasing deformation and fragmentation of the human figure – irrevocably altering the vernacular of visual art in the process, and finally discovering ‘Picasso’. Here, speaking to us during a visit to the Fondation Beyeler show, Claude Picasso – the son of Picasso and Gilot, head of the Picasso Administration, and a filmmaker and photographer in his own right – discusses his father’s formative years as painter, while sharing some of his earliest memories of the artist and his honorary grandfather, Henri Matisse.

“People often ask, ‘What was Picasso really like?’ and I can say that he was a good father and a fantastic artist, but that’s also quite obvious – to everyone. I guess the problem is that he is not a human being any longer; people have made him into a myth and have forgotten the actual person. Of course, it’s easy for me to say this because I have known the real person and when you have such a father, and he’s the only one you have, you don’t pay too much attention. He’s just your father. As I grew up, I would sometimes pick up on things that were perhaps a little bit different from the way other people reacted or behaved: sometimes it was amusing and pleasant and sometimes, for a child, a bit confusing.

“I was very enamoured with Matisse and my father was very, very annoyed about it” – Claude Picasso

“Another thing that I was a little confused about when I was young was Henri Matisse. I thought he was my grandfather because he was always in bed when we went to see him and I had a great-grandmother in Paris who always was in bed when we visited her. Matisse found me rather agreeable: he used to call me ‘my little Hercules’ because I would move everything around in his room and jump on the bed with him and so on. His own grandchildren were not allowed to do any such thing. They were always told to ‘stay against the wall, sit on the chair, don’t move!’ but I could come in and leap about and have great conversations with him. I was very enamoured with Matisse and my father was very, very annoyed about it – mostly because, on top of everything else, whenever I did a little doodle or drawing, I would sign it ‘Henri Matisse’!

“What did my father teach me? He was not the sort of person who would make great big dissertations about whatever he was doing; he was a man of few words. But I watched him and made some ideas in my mind from his attitudes, his way of doing things. I think he was very brave. He taught me how to take risks. It was also quite amazing to watch him work – he would just walk into his studio and start. There was no hesitation, no fumbling about, no having a little drink or nodding his head and wondering, ‘what’s next?’ No, he would just go right to it, straight away. That was impressive. He just couldn’t wait to get into the studio, there was always something going on. Mostly he never had people sit for him; he would always work from memory, work from within. It’s a very profound thing to imagine.

“I think he was very brave. He taught me how to take risks” – Claude Picasso

“What we see in this show, specifically, is Picasso under construction. We start with his arrival in Paris, being absolutely stunned and bewildered by ‘gay Paris’ and the incredible life, the wonderful liveliness he discovers there. Then he starts to live in Paris and it becomes much more difficult; more real. He becomes involved with, and pays attention to, the people around him and their lives, which are very hard. Even though – as you can see from the paintings – he frequents with people from the circus, it’s not all amusement. The only thing that really gives him a sense of affirmation is his work. And work is not easy either because breaking away from a decorative, easy way of painting – as he wished to do – is a hard job. A big, big job.

“He undertakes this task by taking away all of the Fauvist and Impressionist elements – the colourful things – and reducing everything to a minimal amount of colour. At first he’s a little bit nostalgic and melancholy and so he opts for this blue – which is not all blue actually, it’s just gloom and doom. Then he tries to put some light into this. That’s why when he goes off to Gosol the tone shifts. There he sees the light again – the weather is different, the sky is different, the colours around him are different – they’re all very mineral, and so he starts to use only mineral colours, just earthy colours which are the most minimalistic of all because they’re from the earth. There may be a little bit of charcoal or black or white chalk in there but otherwise it’s just this distilled essence, something in between clay and rock – it’s the basic elements of life. This period has been called the Rose Period, but in fact it’s not rose, it’s earth.

“After all this dry, minimal kind of painting, he has found Picasso. And this is a great achievement because this is going to revolutionise everything in art” – Claude Picasso

“Then a little bit later Picasso runs into ‘primitive art’ and this gives him a clue to the fact that you don’t need necessarily to imitate nature, you just need to express what it can be, and what the essential elements are: the vision, the sound, maybe the smell; the senses and the sexual aspect of things. And I think that’s what happens when, all of a sudden, at the end of the show, you see that he has found ‘Picasso’. After all this dry, minimal kind of painting, he has found Picasso. And this is a great achievement because this is going to revolutionise everything in art as we see it now. Because all of us today see as Picasso sees when he becomes ‘Picasso’. It’s a different world, a different thing. It kicks in everything – it kicks in beauty, kicks in the academy, the beauty standards of the academic world, and it goes on from there. And then because he’s knocked everything down, he has to reconstruct it, and from this point onwards he’s constructing art ‘after Picasso’, and that’s the next step. And he spent his life doing that.”

The Young Picasso – Blue and Rose Periods is at Fondation Beyeler until June 16, 2019.