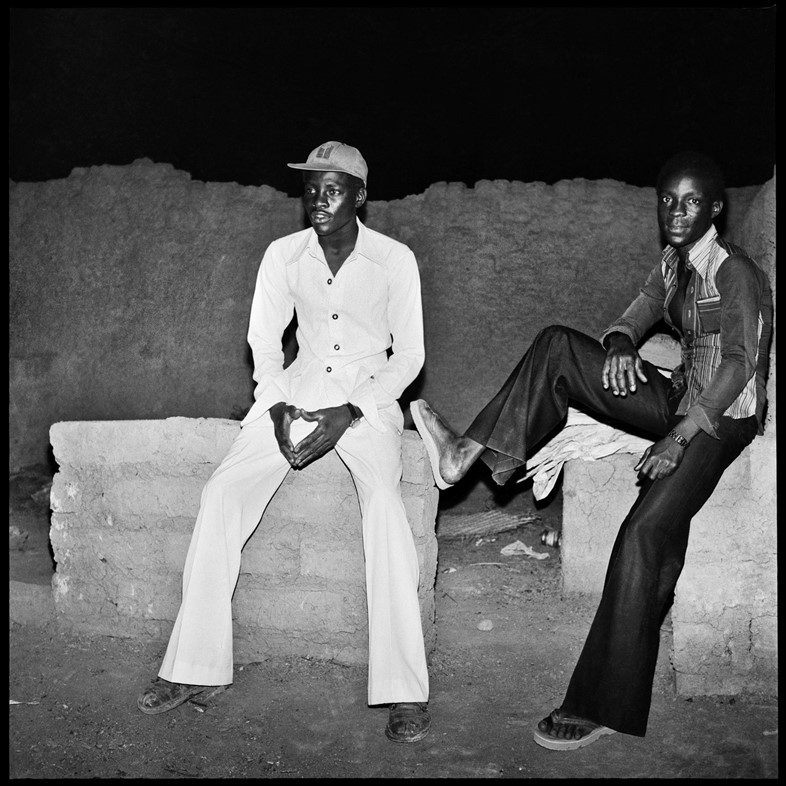

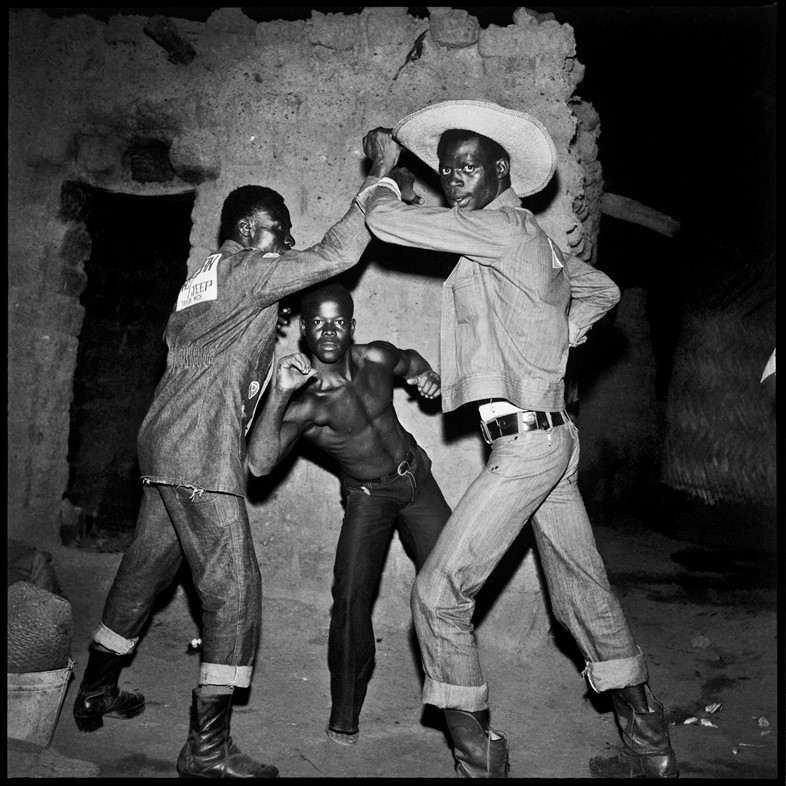

Sanlé Sory’s portraits of the vibrant nightlife of Burkina Faso are showcased in a new exhibition at the David Hill Gallery in London

- TextMarta Represa

When Florent Mazzoleni first met Sanlé Sory, he was burning his negatives. It was 2011 and the music producer was in Bobo-Dioulasso – Burkina Faso’s second largest city – to look for local music of the yé-yé era. He had found Volta Jazz – a band whose sound fused Burkinabè music, modern pop and 50s American R&B – whose album covers astonished him. He set out to find the photographer, Sory, who he eventually discovered sitting outside his studio, burning those negatives.

“I was a little disheartened at the time,” recalls Sory, now 76, speaking over the phone from Bobo-Dioulasso. “The storage space in the studio wasn’t the best. Mice would sometimes sneak in and have a little negative feast,” he laughs. With the help of Mazzoleni (who now considers Sory part of his family), the photographer has since gone through the tens of thousands of negatives that comprise his archives. News of Sory spread, and his photographs have since become the focus of exhibitions at David Hill Gallery in London, the Art Institute of Chicago, Yossi Milo gallery in New York and now David Hill Gallery again, where his snapshots of nightlife around Bobo-Dioulasso are being displayed for the very first time.

Becoming a world-famous photographer, though, was never part of Sory’s plans. “Frankly, I’m overwhelmed by all the attention. But also very, very happy,” he says. When he first decided on his career, the main priority was simply “to earn 10 francs. 10 francs to pay for couscous to eat.” Interested in art since his youth, Sory discovered photography in Ouagadougou in 1957, the day he got his portrait taken for an ID card. “They charged 200 francs for four pictures, which was pretty expensive at the time. As I was paying, I thought it would be quite nice to do that for a living.” That was that; not long later he gave 25,000 francs and a whisky bottle to a Ghanaian photographer named Kojo Adamko, who taught him everything he needed to know, while his cousin, Volta Jazz’s founder Idrissa Koné, helped him establish his studio in Bobo-Dioulasso, which he named Volta Photo.

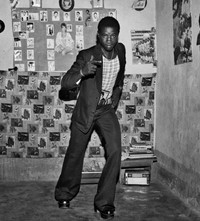

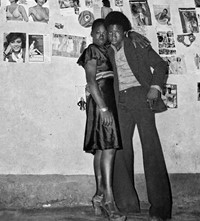

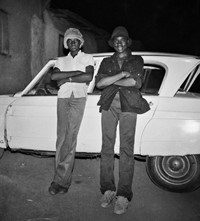

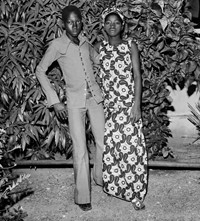

It was 1960, the year Burkino Faso went from being a self-governing French colony to a fully independent nation. A sense of freedom, happiness and optimism was in the air. “People wanted to be themselves,” remembers Sory, which likely accounts for the increase in popularity of Studio Volta. What started as a business for ID photos – there were only three studios in town at the time – soon expanded into the go-to place for full-length single and group portraits. Promoted largely by word of mouth, Volta Photo attracted clients from the city, but also from the surrounding villages and even from the neighbouring country of Mali. “The Malians were the first to come in with five to ten different outfits,” Sory recalls. His own studio props also got more and more sophisticated: clothes, ties, sunglasses, radios and telephones completed a series of set designs made from market-sourced textiles and painted backdrop papers mimicking the beach, an airplane, or even the real street where the studio was. On top of this indoors work, Sory, armed with a Rolleiflex camera, was also covering wedding parties and the unfolding nightlife at Bobo-Dioulasso’s hippest venues – the Volta Dancing, the Calebasse d’Or, the Normandie and the Dafra Bar.

“Then this idea came to me. I had a pickup truck, a generator, an amplifier and loudspeakers; so I decided to take them with me to the countryside. I would set them up in someone’s bar, and if there was no dance floor we just watered the ground to keep the dust down. We sold tickets and I went around taking pictures of the people, that they would later buy.” Those parties were baptised Les Bals Poussière (“The Dust Balls”), and they brought together the vibrant music, fashion and youth culture scenes of the time. “They became incredibly popular,” says Sory.

This went on until 1987, when a coup took place. Curfews were established in cities, and laws prohibiting bands from charging money for concerts were enforced. The shift was not just political; it was also cultural. “It’s all about colour these days. Nobody likes black and white pictures here anymore. It’s a shame,” says Sory. “When people see themselves in black and white pictures they say, ‘I’m too black in this one.’ People want to look white. What I say is that you should be the way you are.” Sory now owns a few digital cameras (all presents from Mazzoleni) and still sometimes takes pictures at the local markets. The studio – in a smaller space – is still there, and he even accepts commissions. “If they call me, I’ll come and cover weddings and christenings. Otherwise I don’t go. I’m tired,” he confesses, laughing. “But I’m happy.”

Sanlé Sory: Peuple de la Nuit is at the David Hill Gallery from April 5 – May 31, 2019.