Gallerist Paul Stolper and ICA director Stefan Kalmár discuss the history of editioned artworks and their potential for artistic and political expression

- TextDaisy Woodward

Editioned artworks have a long and storied history, dating back to the Old Masters like Rembrandt, whose print production was, by necessity, curtailed by the swift degradation of his printing plates. In the centuries since, artists have exploited the multiple – in print and object form – as a means of disseminating ideas, of untethered experimentation (especially in the endlessly adaptable medium of print), of democratising their work and subverting the very idea of the artwork as a one-off, fetishised object.

Few understand the power of editions better than London’s Institute of Contemporary Art, which has supported the experimental interdisciplinary practice of contemporary artists ever since its opening in 1946. The same applies to London gallerist Paul Stolper, who established his eponymous gallery in 1998 and has henceforth worked directly with many celebrated artists to produce limited edition prints and sculptures. Who better then for the ICA to collaborate with for the latest iteration of ICA Artists’ Editions – an important means of funding for the institution, ongoing since 1991, which sees artists donate editions to the ICA, for exhibition and subsequent sale?

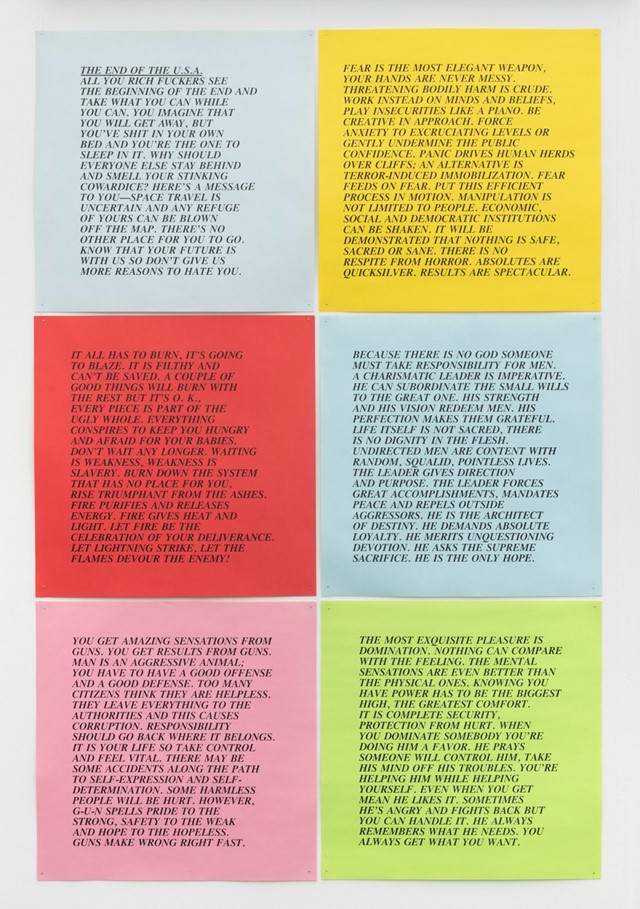

ICA Artists’ Editions + Paul Stolper Gallery opened this weekend at Paul Stolper’s Museum Street location and proved a delight for art lovers and buyers alike, allowing visitors to view and purchase a number of rare editions from across the past 40 years, from such icons as Peter Blake, Peter Saville, Jenny Holzer, Jeremy Deller, Brian Eno and Sarah Lucas. It showcases the remarkably broad potential of the format and the numerous ways in which artists have engaged with the concept of editioning, from Holzer’s seminal Inflammatory Essays – which she fly-posted on multi-coloured paper around New York in the late 70s, thereafter recreating them in edition for the ICA in 1993 – to Blake’s covetable Art Jak, an eye-popping sports jacket commissioned by the institute in ‘78 to raise money for their programme.

Here, on the eve of the exhibition’s opening, we sit down with Stolper and the ICA’s director Stefan Kalmár, who since taking on the role in 2016 has devoted himself to reinstating the ICA’s radical founding principles, to discover more about the fascinating history of editioned artworks and their multifaceted potential for artistic and political expression.

When did you both discover and fall under the spell of edition artworks?

Paul Stolper: Probably in my teens – a Picasso print. I was always amazed at the sheer number of prints Picasso made and the extreme subject matter he was able to tackle so freely in print form. It seemed like a whole world apart from his paintings and drawings. Then, by default, I ended up studying the history of drawing and printmaking at Camberwell and discovered that if you go to the British Museum they let you handle a Dürer woodblock – it’s history in your hands. Prints weren’t framed so much, so you’d be able to touch and really look at them – the plates too. Then, in 1991, I began working with a couple of Goldsmiths artists and saved up all my money to buy copper plates, a Winchester of acid and a cloth. I took them to a printing studio and everyone just got pissed for a week! It wasn’t till the last day that I said, almost in tears, “You’ve got to do some prints!” They finally brought it out the bag and did a series of prints, and I really enjoyed being a part of that process of fabrication.

Stefan Kalmár: Historically speaking, producing prints or multiples was considered a more democratic and more accessible form of contemporary art distribution, and a more radical one. About 40 years ago, the ICA started producing editions, not only to finance the institutional programme, but also to make content more accessible; to democratise contemporary art practice. I personally really admire Jenny Holzer. A) because her editions resonate with the contemporary condition of America today. And B) because her work in the show is an unlimited edition, unsigned, yet it still creates a market value which is interesting.

PS: You’re right, that idea of democracy is really important. And editions can resonate over a long period of time. For the piece I did with Jeremy Deller in 1998, The History of the World, he was adamant that it would be almost like a hundred prints for a hundred pounds, printed at St Martin’s. It was such a beautifully simple process – it’s kind of mind thoughts and spontaneous drawings; a single colour on black paper. And it seems to continue to resonate. Prints have that ability – they’re a great resource for artistic energy that can be used in lots of different ways across different media.

SK: Also, artists learn from the legacy of print. If you look at a contemporary artist like Cameron Rowland, for example – whose work you can’t buy, only rent – this speaks to a similar idea of ownership and exclusivity. Editions are tied up with the defetishisation of commodity objects – when you’re creating not one work, but hundreds of them, what does it do to the perception of art? Historically, at least, editions are the starting point for this question. Obviously, in the meantime, capitalist structures have caught up with the multiple or edition – there is now a very distinct edition market – but I do still think that that idea is at its core.

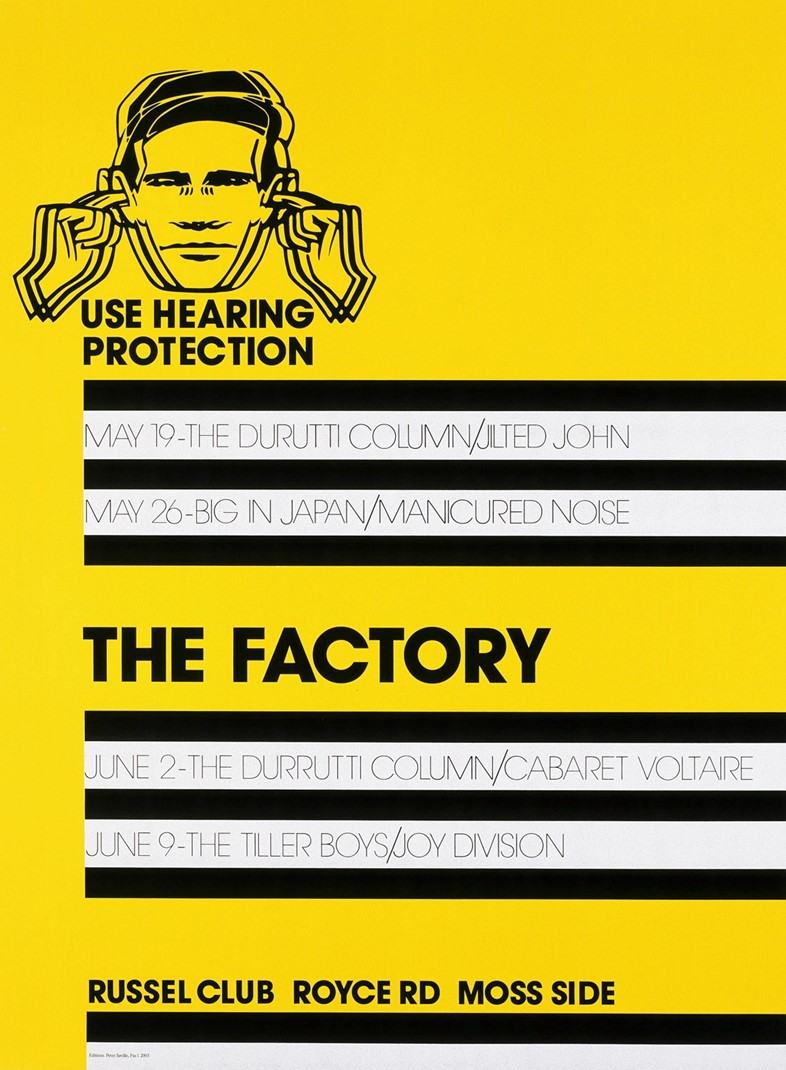

PS: Definitely. When I was growing up, the seven-inch single and the 12-inch album cover was something to cherish. I’m fortunate enough to work with Peter Saville and what he did, absolutely, was to make artworks – but ones that were disseminated to about 500,000 people. Many artists and generations regard the covers that Peter made as icons of design. Is it ‘art’? I don’t know, but it’s definitely some kind of multiple.

SK: Absolutely, and this leads onto the next point which is the different logics and dichotomies between popular culture and the exclusive art market. If something becomes popular, is it then not becoming art? And vice versa. Even today, just because something’s on a record, it isn’t considered an artwork – it’s a part of popular culture. Yet I think edition production continues to challenge exactly that perception.

PS: Exactly. And you’re right about commodification: there’s a great piece by Peter Saville called The Flat Pack Plinth – a readymade flat-pack plinth, that anyone could walk into a shop and buy, then go home and set up. Then anything you put on it becomes art, just by the very nature of that accessory to an artwork – the plinth. So you’re right about numbers – does it become any less of an artwork because the numbers are greater?

SK: If you go back to people like Lawrence Weiner or, for us, Richard Hamilton, you’ll find that certain politically progressive artists were always interested in the multiple and edition.

PS: It’s dissemination of information, isn’t it? How do you reach a broader audience?

SK: The edition could almost be seen as a record sleeve. Artists like Bruce Nauman made editions you could take away for free...

So what was the starting point for this exhibition and collaboration?

SK: Well first off there’s a similar affinity to artists between Paul Stolper and what the ICA does, historically – with people like Peter Blake and Jeremy Deller. Then there’s the economic aspect: nowadays, institutions increasingly rely on edition production, partly to promote young artists in our programme and also to create revenue for the next generation of artists to produce and create new works. So in a way it’s older generations of artists helping younger ones by donating editions.

PS: I thought the show was a really exciting idea because institutions tend to be very exclusive, with a brand that they’re reticent to share or part with, but it seems that editions are a great way of sharing ideas. It’s also cross-generational. For instance, Peter Blake showed at the ICA in the 50s – he knew Roland Penrose and Lee Miller – and the show will include these jackets that he made in 1978 to raise funds for the ICA, as well as a new print I’ll be launching that Peter’s just been signing off today. I think it’s fantastic that the ICA have decided to broaden their horizon of where they show editions, and of course, you can do that more easily with editions than with primary work, where artists can be a little more protective of where it goes.

SK: I also find that artists often approach editions more playfully or experimentally – you can see aspects of their ways of working that you might not find in their other work.

PS: Definitely. It’s a freedom, probably both mentally and physically, from what they normally do, so they try new things. We shouldn’t look at prints as somehow secondary in any way – artists can come up with really important work that they wouldn’t have thought of doing, or possibly couldn’t do, in their primary market.

SK: Also because of the difference in value – the primary market is always the same of the same.

How did you select which artists or works to include?

PS: I chose some who had a symbiotic relationship to the ICA, like Blake and Saville. Vinca Petersen did a big book launch there; Brian Eno has performed there...

SK: We chose a good overview of our edition/multiple production throughout the past 40 years.

PS: I tried to do that too – there’s a really early Adam Chodzko piece on show; work by Keith Coventry, who I’ve worked with for a long time; Matt Collishaw, who I’ve just worked with recently.

What are some of the most unusual pieces in the show?

SK: The Frances Stark piece is fantastic. It was initially made for Instagram and then she turned it into a print. It’s the Twitter pidgeon shitting on peace and in the top-right corner is war. The relationship between Instagram and editions is interesting too – it’s a bit like record covers.

PS: I think the breadth of media offers a great overview of print and edition making: a Brian Eno etching, Jeremy Deller silk screens, Keith Coventry linocuts. Sarah Lucas’s work is on folded advertising paper. I like that subversion – normally a print’s exclusivity and value lies in its being perfect but all these works were pre-folded because that’s how the paper came.

SK: Often, historically, prints reflect the media itself. If you look at Barbara Kruger or Frances Stark or Jenny Holzer, there’s an aspect of self-reflectivity in terms of distribution, democratisation and the idea of the published, public artwork.

Finally, what do you hope people will take away from the show?

SK: An artwork! (Laughs) To support a future generation of artists and the ICA’s programme. And the work’s affordable.

PS: I like this sense of non-exclusivity between the ICA and myself, this breaking down of that sense of ownership that galleries and institutions have traditionally had.

SK: This idea of not-for-profit works with a for-profit entity wasn’t thinkable 20 years ago, so maybe this will speak to the contemporary moment that we need to break out of old dichotomies.

ICA Artists’ Editions + Paul Stolper Gallery is at Paul Stolper Gallery, from January 12 to February 16, 2019