The Anti-Tom of Finland: Meet the Artist Who Redefined the Queer Aesthetic

- TextHynam Kendall

Ahead of his upcoming New York show, Hynam Kendall meets Mel Odom – one of queer art’s most intriguing figures

Where would queer art be without Mel Odom? Bear with me, this is not didacticism as means of clickbait.

Before Odom, the queer aesthetic was denoted in essentially one way: men were chiselled, defined to balloon proportions in hypermasculine guise. Muscles were superlative and angular, Tom of Finland being the best example of this. The art made readily available seemed only to want to promote homosexual desire as one thing: heterosexual-passing. Men were exaggerated men with an added dose of manliness.

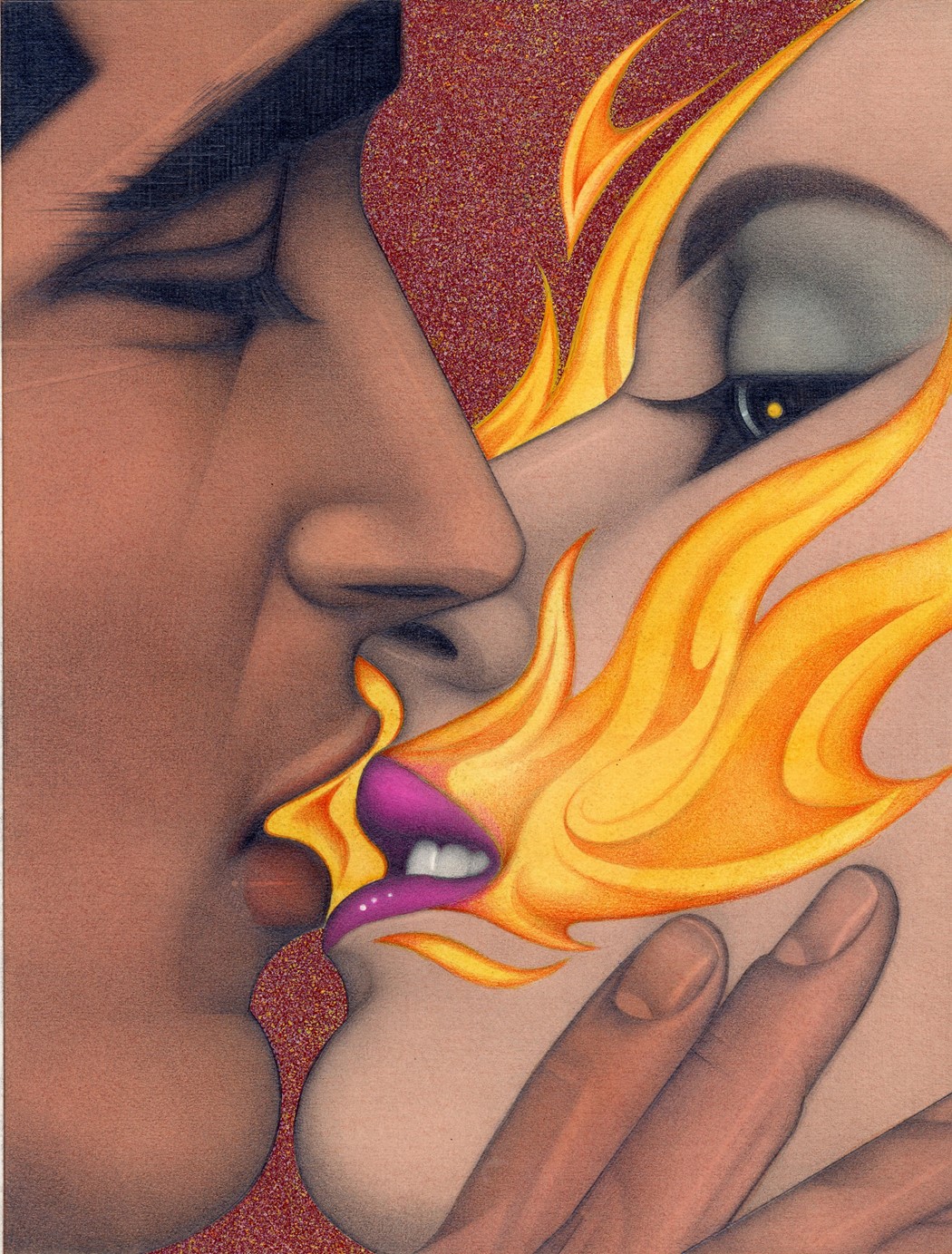

When Odom’s soft, seemingly airbrushed male figures reached peak mainstream during his award-winning and still lauded tenure at Playboy, where his delicate and dreamy men accompanied stories by the likes of Joyce Carol Oats – the viewing public were finally seeing male figures of lust depicted lovingly, softly. Men were presented in the commercial sphere as only women had been before. It is a seemingly small act, but the repercussions were widespread. Homosexuality was rapidly opened out to a spectrum of portrayal: hard, soft and everything in between.

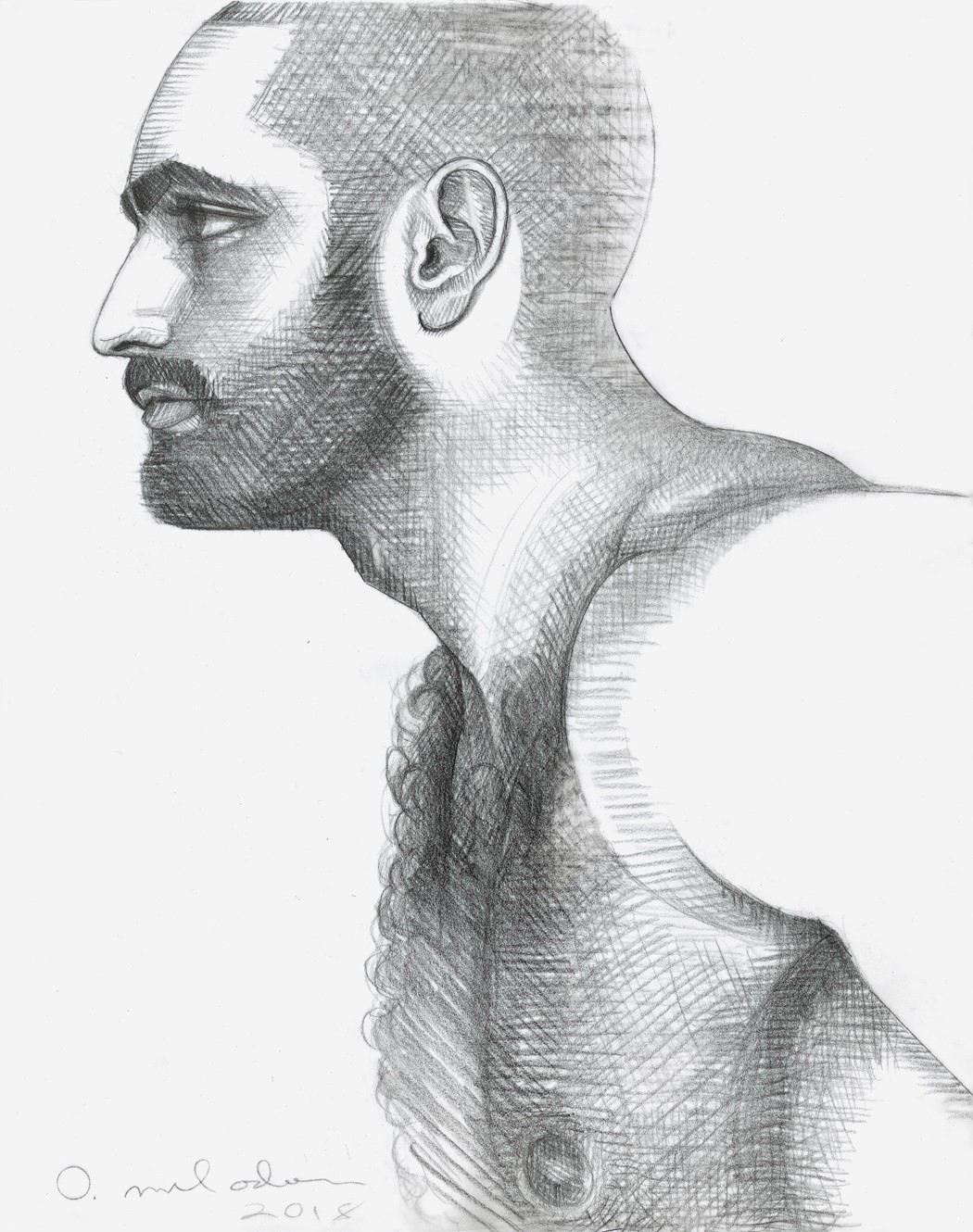

This month, Daniel Cooney Fine Art gallery assembles decades of the American artist’s work in a retrospective aptly titled Gorgeous. The exhibition features a vast selection from Odom’s own private collection, as well as iconic pieces from his time at Playboy, and even, for the avid fan, never-before-seen drawings. In anticipation of the show, Odom talks to Another Man about his dark, dreamy aesthetic and what it means to be a successful queer artist whose work spans five decades.

Your show is called Gorgeous. I wanted to discuss your relationship with that word and why it best describes your work.

Mel Odom: It’s much less used than ‘beautiful’. It’s kind of archaic. And as though it has a little something extra. There’s also a sense of camp to the word!

The narrative of the show is essentially a biography, are some pieces more personal than others?

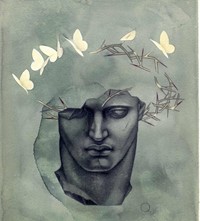

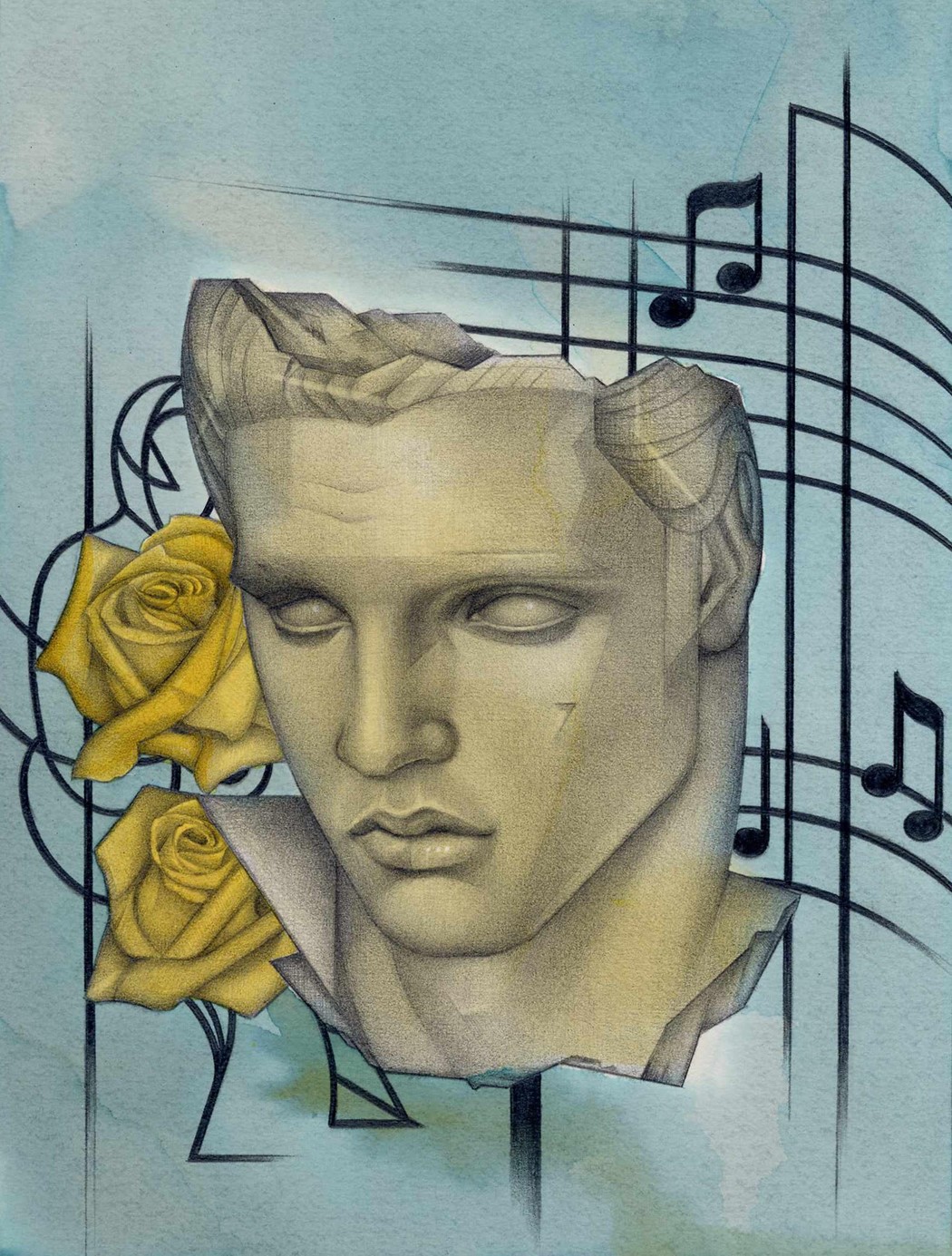

Mel Odom: There’s a drawing that I did called Crown of Wings. It was done during the [AIDS] epidemic and I was so sad about having so many of my friends dying. Valentino was coming out with a men’s fragrance and they had set me an assignment for it, but it never happened. I had done a drawing of a statue head for them and just felt like the broken face was so beautiful and so poignant, so I did this second drawing for myself. As I said, my friends were all dying and it was not something I was able to put into words so this was my way to say it – that I was missing them.

You had quite a small town upbringing in North Carolina. Growing up, what art did you have access to?

Mel Odom: Really, very little. It was a tobacco farming community and my dad had a tobacco farm with his sisters, so it wasn’t an ‘arty’ environment. About the time I turned seven my parents paid for me to have drawing lessons after school with a lady in town and she had art books I could look at, but I suppose the art I saw was predominantly illustrations in magazines. Beautiful drawings of Jell-O and women’s make-up and hats in the adverts. That was what I saw and that was what I thought was beautiful. There were no galleries to go to but lots of magazines.

So your parents didn’t have an interest in art?

Mel Odom: No, no. As well as having the farm, my father was a mailman and my mother was what they would call ‘a simple housewife’ back then. I’m sure she was just thrilled that I would have something to do that would keep me quiet and out of the way. Locally I became pretty exotic, teachers would come to me and request drawings. I was known as the little artist of the town!

Once you discovered art, which artists and artworks helped guide your visual identity?

Mel Odom: Aubrey Beardsley. He was and is my favourite artist. When I was 15, Life magazine did a fashion layout of black and white fashions against huge blow-ups of Beardsley drawings. I had never seen his work until then and I just went crazy. I started drawing in pen and ink to copy him. Also, I grew up watching a lot of cartoons and, oh gosh, that informed me too. Very much. Popeye – I still watch Popeye every Saturday morning – and Disney’s silly symphonies… Disney actually probably is one of my earliest and most important influences.

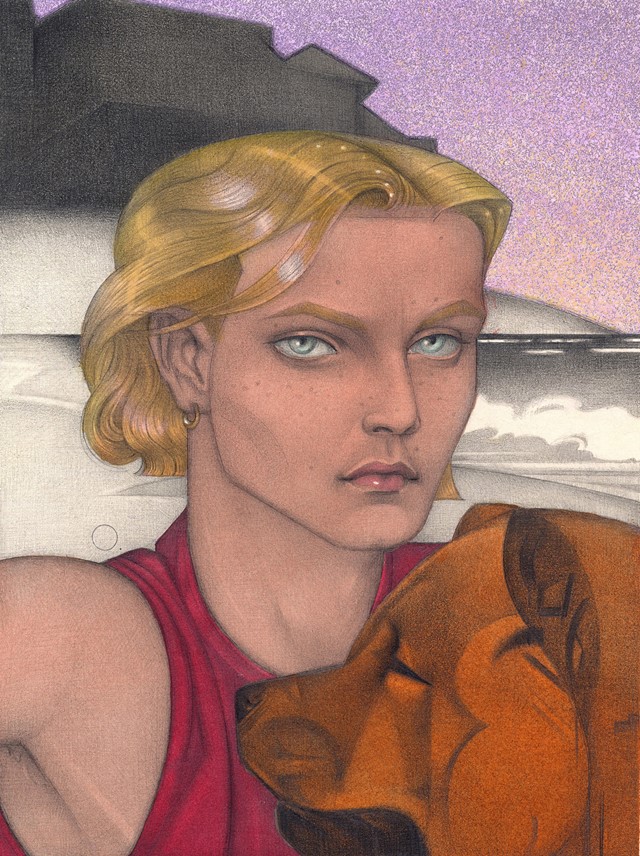

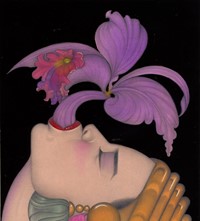

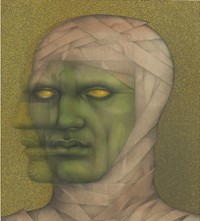

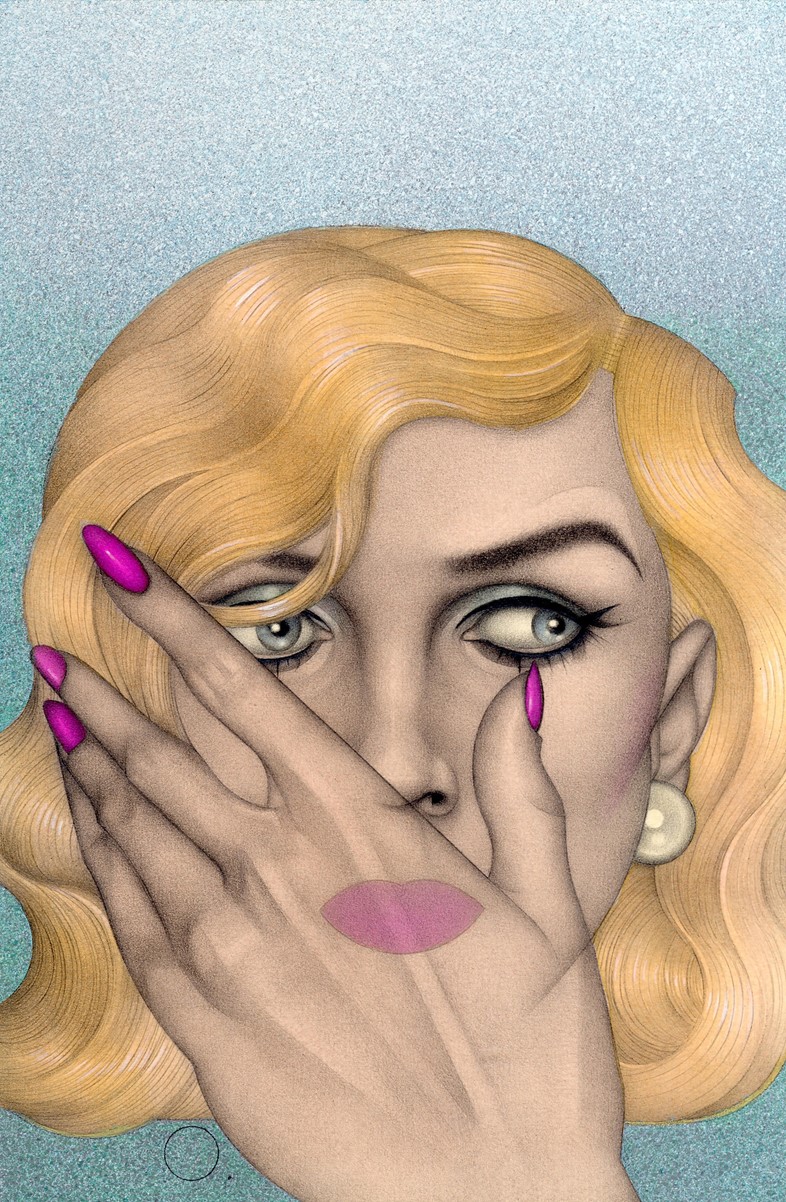

What denotes a Mel Odom?

Mel Odom: Usually there’s a degree of sensuality and a poetry about it. This sounds quite pretentious and I don’t usually say this, but I think of my artworks as visual poems. I was an illustrator for 20 years so there’s also a technical and meticulous element to it. Drawings can take weeks on end. And it’s pencil, it’s not airbrush – people think it’s airbrush but it’s not. It’s never been airbrush, I’m such a puritan. I feel like now there aren’t a lot of people who can do what I do. It’s the process of doing it that is so exciting to me: I’m alone, smoking weed, and it’s just me and the piece of paper for weeks. I also think there’s a precision in my drawings that happened because when I first moved to New York in 1975 it was pretty wild, I was as big a hick as was possible and I couldn’t control what was going on around me, so I put the control into my art.

Your works have been described as queer, do you agree with those allusions?

Mel Odom: Yes I do because they’re beautiful.

What is queer aesthetic and how do you think you fit into it?

Mel Odom: The first book cover I ever did was for a book called Nocturnes for the King of Naples by Edmund White and it was a very, very successful book. It was a picture of a guy but I drew him as a love object not as a lust object. I drew him the way people generally depict women – I made him very sensual. I was doing the anti-Tom of Finland, and depicting men and male love in a dreamy way. I think I helped change or add to the queer aesthetic in this way: with softness. With no hardness at all.

I’ve read interviews in which you refer to yourself as an illustrator – do ‘illustrator’ and ‘artist’ exist independently?

Mel Odom: I generally don’t believe that there is a difference. You know, the Sistine Chapel was illustration. I mean it was Michelangelo depicting what the church was selling. Once I started thinking about what paintings had been all along and what they were used for, I think I realised that art becomes illustration from a distance. I’ve been lucky enough to be commercial in my career, and if it’s done commercially it’s considered illustration. But I’m a little squeamish calling myself an artist because I feel that’s for other people to say.

Some of your most iconic illustrations came during your time with Playboy.

Mel Odom: Thank you! They approached me. They had seen my work in Blueboy magazine. They were known for their quality back then, so I was illustrating for people like Joyce Carol Oates and Tom Robbins. I was doing enviable assignments and I was 27! It was a dream. They would enter all my drawings in illustration competitions, and off the back of it I was winning all kinds of awards! I worked for Playboy magazine for 17 years. And these drawings of mine would go all over the world, literally; Spanish editions, French editions… my images sold farther and wider than I could ever have imagined.

It was thanks to working with publications like Playboy that you gained a huge international commercial success. Was this ever a burden?

Mel Odom: You know the thing about being an artist is that somebody still has to pay the bills. And regarding commerciality: I wanted people to look.

But what were the downsides to your commerciality?

Mel Odom: There were galleries who wouldn’t even look at my work because I was a successful illustrator and that bothered me. I felt that my work was heartfelt enough to stand on its own without whatever article it had accompanied. It hurt. It still hurts. But you know what, then you see your drawing on the cover of Time magazine and you think, ‘Fuck you!’ I’m on the cover of Time magazine you fuckers!

Mel Odom: Gorgeous is at Daniel Cooney Fine Art, New York, from January 10-Feburary 23, 2018