Bobby Gillespie on the Making of Primal Scream’s Latest Release

- TextTom Connick

Speaking to Another Man, Gillespie reveals the story behind Give Out But Don’t Give Up: The Original Memphis Recordings – a record which, after 15 years in a box in an attic, is finally seeing release

Screamadelica was a show-stopper. The third studio album of Scottish rockers Primal Scream, its day-glo, sunshine-daubed artwork remains one of British music’s most iconic visuals. Big, brash and with over three million sales under its belt, the record won the first-ever Mercury Prize, and came to define the rollicking, anything-goes pace of the 90s.

But how do you follow an album like that? With Screamadelica’s rocket-speed breakthrough, Primal Scream had become a household name but, as the addiction and excess of that rock and roll dream came to a head, they were faced with the need to follow up a record that had shifted everything around them. In typical ‘fuck you’ fashion, Primal Scream opted to shred everything they’d come to be known for.

Give Out But Don’t Give Up: The Original Memphis Recordings is a snapshot of those years. A recording session that cast aside every idea of what Primal Scream could or should be, it’s a fascinating artefact of British music history, which highlights the band’s incredible, encyclopedic musical knowledge – and which almost never saw the light of day. Locked away in a box in an attic, deemed too much of a departure from their tried-and-true sound, the sessions were shelved in favour of a re-recorded, less experimental reworking of the record. Recently uncovered and finally released, 15 years on, The Original Memphis Recordings is a marker of the band Primal Scream once was, and a pointer to a freer future.

“It was just quite foggy, I think we just got wasted – really, really wasted – and then just jammed” – Bobby Gillespie

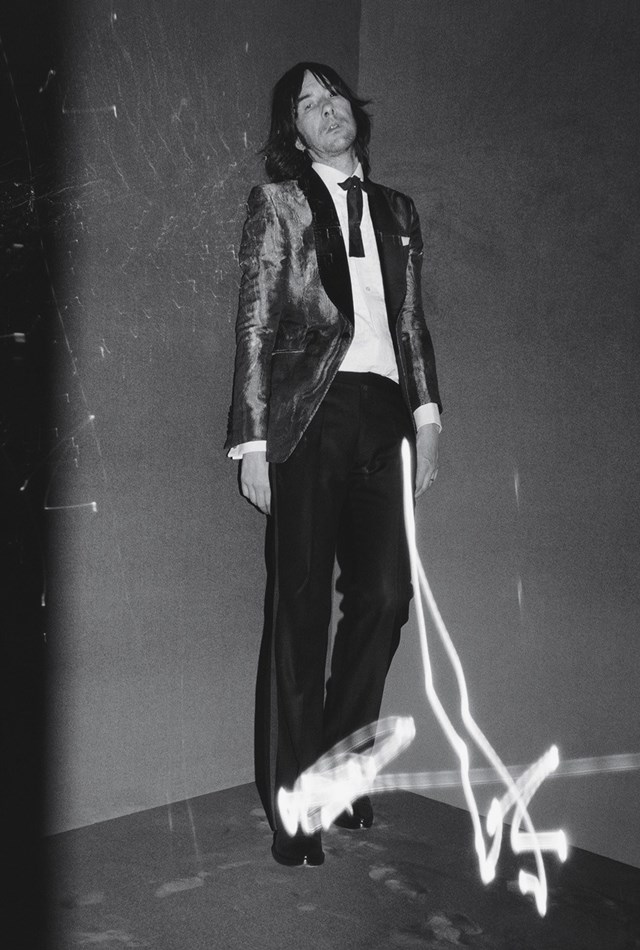

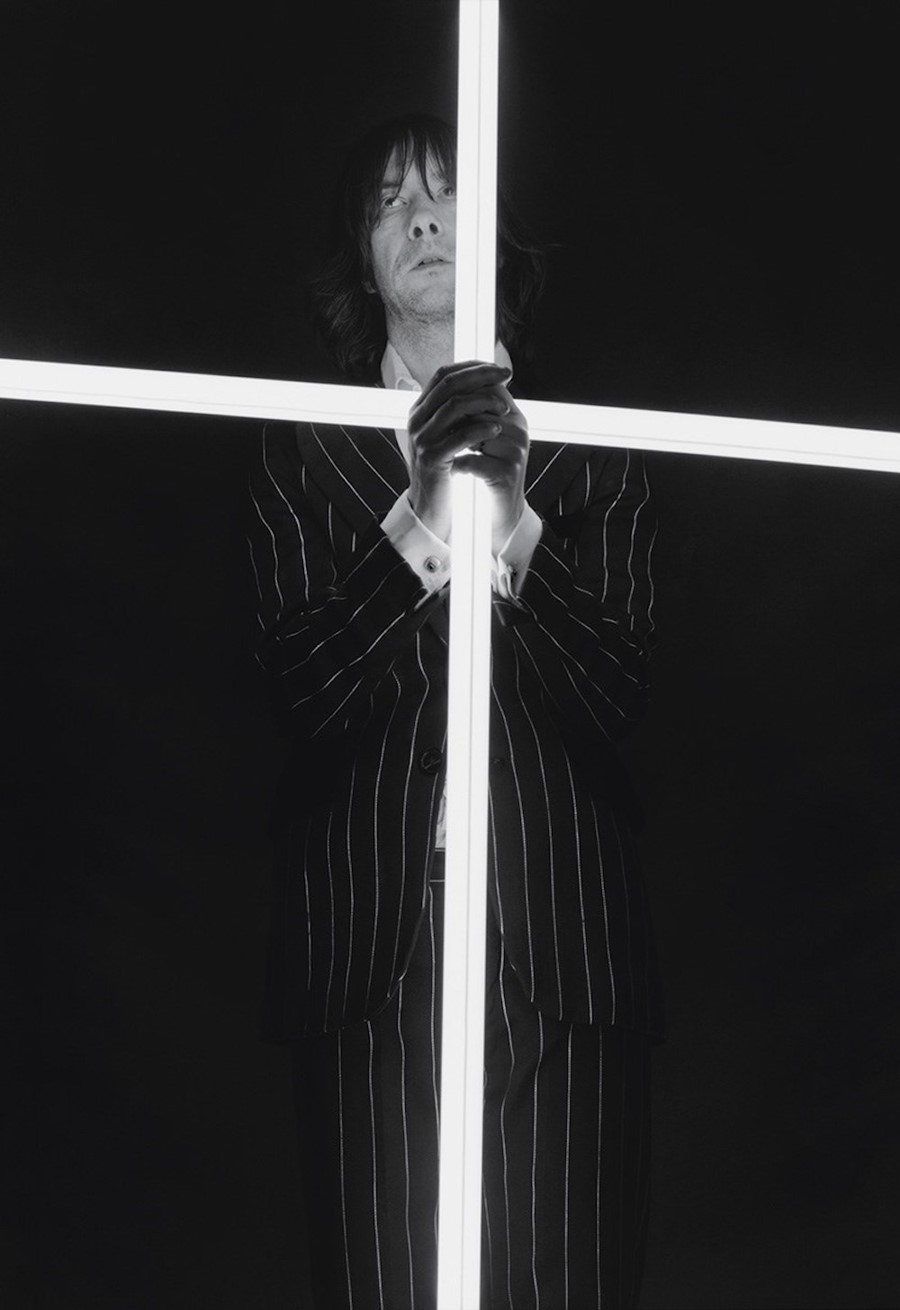

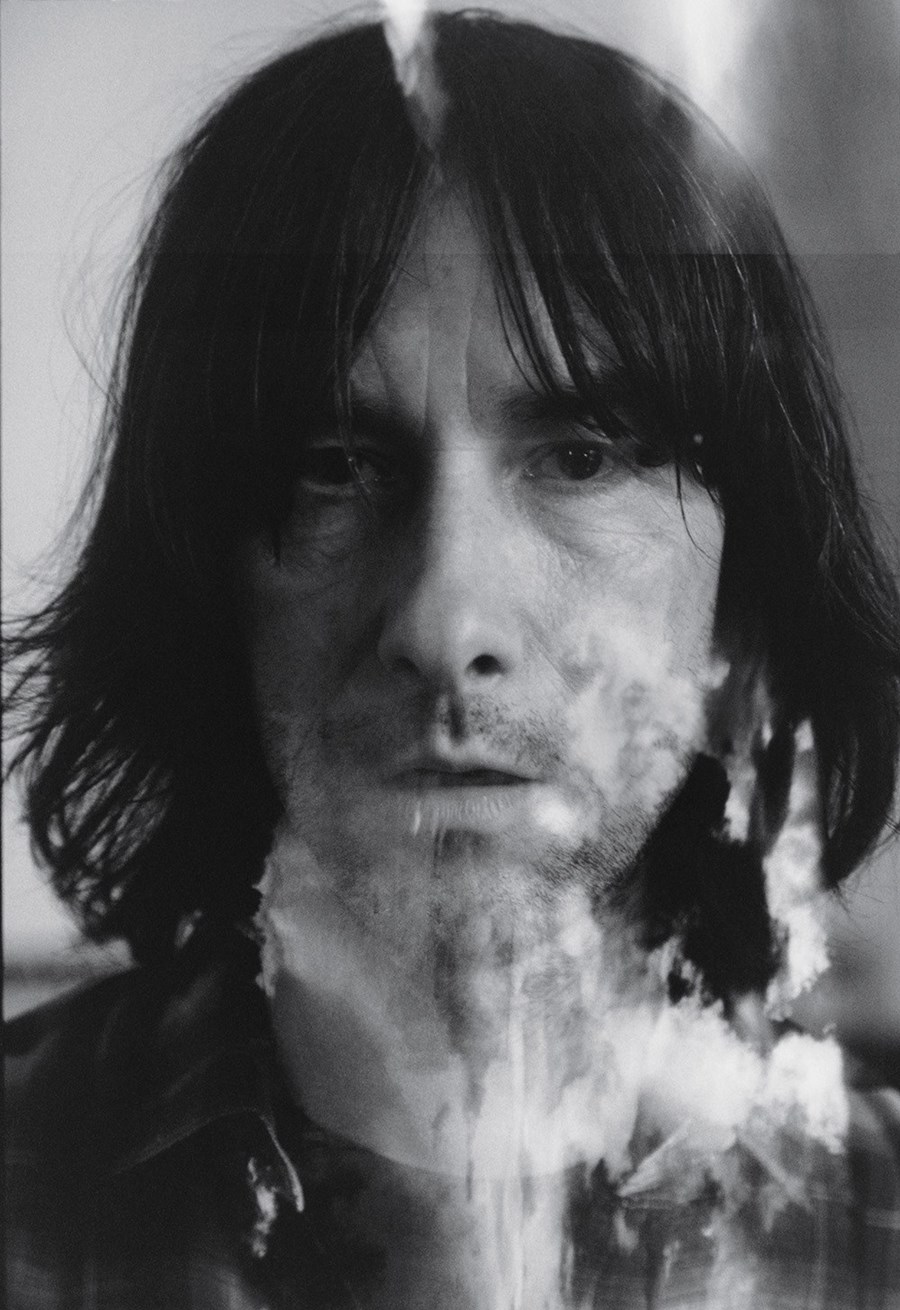

Today, Bobby Gillespie cuts a rather more placid figure than the brash, early 90s superstar you might imagine. In an east London photo studio, he sips back on a coffee, recalling those post-Screamadelica days with a slight weariness, as if he’s right back there in the maelstrom. “We were a bit burned out,” he says understatedly, recalling how, at the tail end of 1993, Sony and their management had pushed them into a Camden studio, eager for a follow-up. “We basically had no songs, so nothing really got done,” he shrugs. “It was just quite foggy, I think we just got wasted – really, really wasted – and then just jammed.” The frustration from their label and management didn’t help proceedings, either. “There were various addictions going down as well,” he continues, “so it was a lot of drugs – I guess somebody probably thought, ‘If we give them something to do, they’ll make something.’ But it’s not that easy – you’ve got to have the songs.”

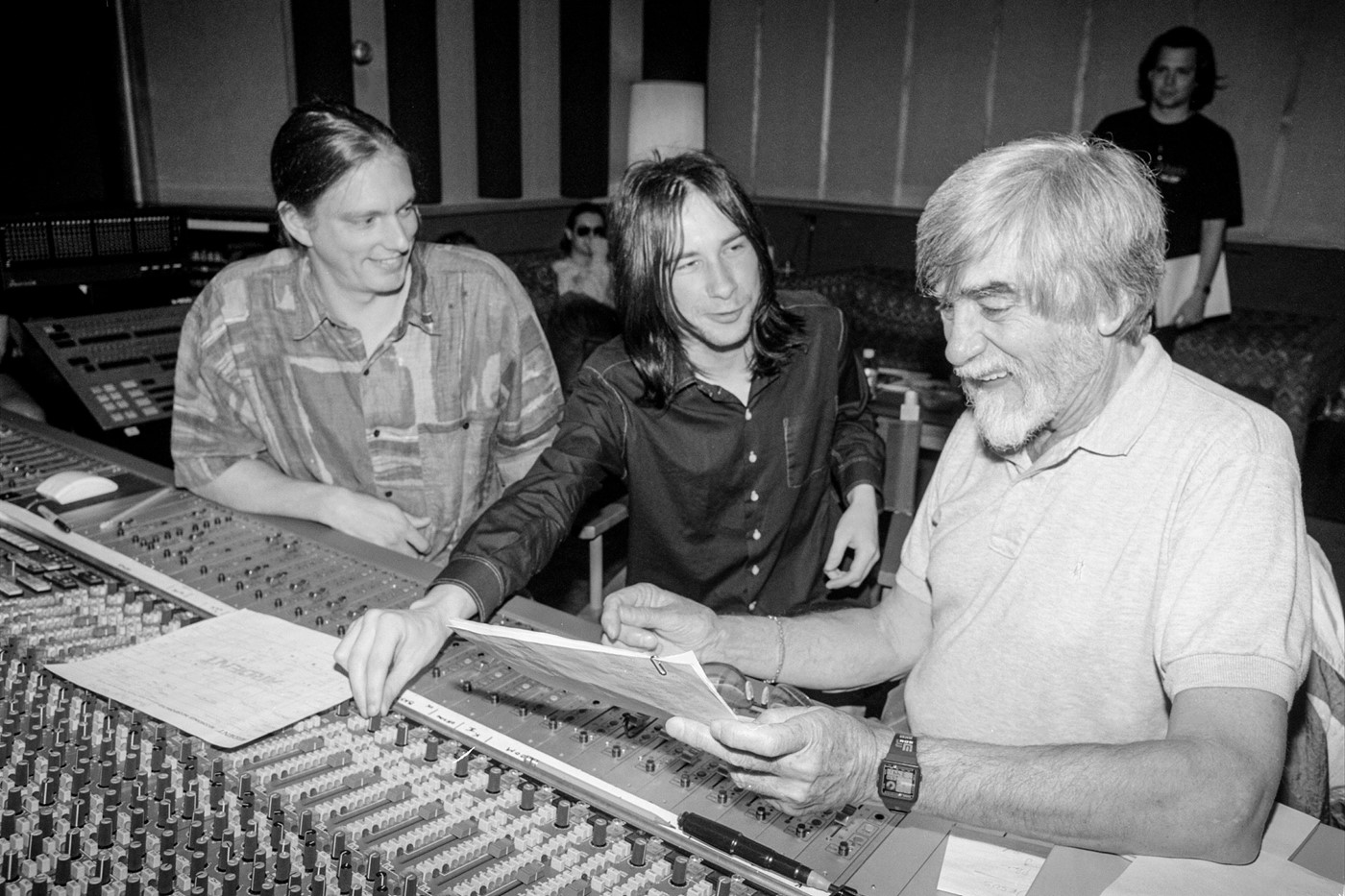

Sinking back into the background, and free from the pressure of incessant touring and forced recording sessions, the band finally began writing. What emerged was a total surprise. “Most of the songs were ballads,” Gillespie explains – a world away from the stomp of Screamadelica. “We were writing five, six, seven-minute country-soul ballads.” A heel-turn though it may have been, it was a fresh start that they decided to roll with. They recruited a new rhythm section out of highly-sought drummer Red Roger Hawkins and bassist David Hood, whose previous credits ranged from Aretha Franklin to Wilson Pickett. “We kind of felt they were the right guys, with the right sensitivity for these ballads, because we wanted to make a grown up, sophisticated, well-ranged, beautiful soul record,” says Gillespie. Securing Tom Dowd as producer – whose work alongside Aretha, Rod Stewart and Dusty Springfield was equally cut away from the Primal Scream of old – the scene was, finally, set. “And then… we went to Memphis.”

“It’s a very emotional record, and I’m very proud of it” – Bobby Gillespie

Gillespie talks of those Memphis days with an infectious excitement. Reeling off drum sounds, recording techniques and producers for more records than most people hear in a lifetime, his encyclopedic knowledge of soul and classic R&B ebbs and flows in The Original Memphis Recordings. Every member of their newly formed line-up pitched in, each song freely evolving as they explored these new sounds. “There’s some really beautiful stuff on there,” he enthuses. “There’s A Big Jet Plane that’s got wurlitzer piano and electric sitar,” he says, laughing at the absurdity of those gentler instruments falling in line with Primal Scream’s perceived image as hard-edged rockers. “But I love it! The feeling is beautiful. The reason we wanted to work with Roger and David was to feel the amount of soulfulness they have when they’re playing, and the gentleness of their touch.”

Given Gillespie’s palpable pride in the recordings, it feels impossible that such a record could have been shelved. Upon finishing the sessions, the band went their separate ways, leaving Dowd to mix. Returning a few weeks later, they second-guessed what they heard. “Dowd played us the album and, at the time, we thought it was too grown up for us,” Gillespie explains. “We felt maybe a bit embarrassed by it, because we were all such punks; we felt that it should have been more dirty, more fucked up. But dirty and fucked up isn’t what Tom Dowd does – he does sophisticated, beautifully arranged adult rock pop music.” He shrugs: “I just think maybe we’d been out there too long and we should have just all gone home.”

When they returned to London, they ransacked the sessions, re-recording some parts, re-mixing others, and crafting Give Out But Don’t Give Up into the gnarlier version that eventually saw release. “I guess maybe I felt it was too revealing,” he sighs, citing a loss of confidence in the song Free, which he left to Denise Johnson to sing when the time came. “For years I wished I’d sung that fucking song.”

Now, with the benefit of hindsight and a further 15 years of music-making, his view is different. “To me it’s a real, pure Primal Scream record,” he says. “There’s a real feeling of sadness to the record that I love – which we haven’t really done that much since.” That emotional balladry is something that’s not returned to Primal Scream since, either. “I think we were embarrassed by the openness of the emotion, and after that we shut up,” he shrugs. “[Follow-up record] Vanishing Point was dark, XTRMNTR was like that – it was a total ‘fuck you’. There was no feeling – so I guess it’s a good timeline or diary of how we were in the 90s,” he laughs. Turning his attention back to those Memphis sessions, that darkness slips away once more. “It’s a very emotional record, and I’m very proud of it,” he adds.

The rediscovery and release of Give Out But Don’t Give Up: The Original Memphis Recordings has given Gillespie a chance to breathe – it’s the removal of a 15-year albatross that’s been hanging around the band’s neck. Does he finally feel validated, then? “Well… I still wish I’d sung on Free!” he laughs. “I’ll do it for myself some time.”

Primal Scream’s Give Out But Don’t Give Up: The Original Memphis Recordings is out now