A new documentary tells the story of Trojan Records, which introduced Jamaican music to the UK – here, we speak with DJ and radio host Don Letts who experienced it first hand

- TextTom Connick

Launched in 1968, Trojan Records felt alien. An Island Records offshoot which pushed rocksteady, reggae and dub into the realms of British popular music, it was a huge risk, and one of Britain’s first steps towards multiculturalism. At the time of its launch, big-time rock and roll acts were dominating the airwaves, and though the Windrush generation were contributing to British society across the board, they weren’t hearing their own culture reflected back. Trojan changed that, providing Jamaican music with a British outlet for the first time. Taking its moniker from the nickname of one Arthur ‘Duke’ Reid, Trojan Records began issuing records from esteemed Jamaican producers like Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, Edward ‘Bunny’ Lee, and Duke Reid himself. It was a seismic shift in British music culture.

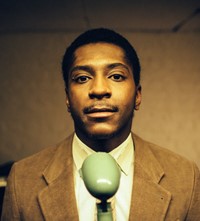

New documentary Rudeboy: The Story Of Trojan Records, directed by the Grammy-nominated Nicolas Jack Davies, chronicles the rise of Trojan, and the political and social movement it both soundtracked and shaped. DJ, radio host and British music icon Don Letts was at the heart of that movement. Trojan, he explains, gave the young, black Don a means to own his heritage like never before. “Before Trojan came along, I was growing up with my white mates, and I’m digging The Who, The Beatles, The Kinks, The Stones – all that stuff. But it was almost like I was a poor relation, because I didn’t have anything to bring to the party.” In 1969, that all changed. A cover of Neil Diamond’s Red Red Wine, by Trojan artist Tony Tribe, hit the charts and the UK caught onto Jamaican music like never before. Where previously British audiences’ sole exposure to the Jamaican music came from novelty hits like My Boy Lollipop, finally it had a serious outlet.

“All of a sudden,” remembers Letts, “I’m holding my head up a bit more. The year after, there’s Bob & Marcia’s Young Gifted And Black – and obviously, for me, that was really empowering. We needed that kind of energy.” Another year later, Jamaican duo Dave and Ansell Collins released Double Barrel, one of Trojan’s most iconic records. It hit number one in the UK singles chart. “Now I’ve got this musical equity with my white mates,” says Letts, “This is what I’m bringing to the party.”

“All of a sudden there was a lot of black acts on Top Of The Pops, for instance. Now, that might seem like a really simple thing, but to my parents, that was like, ‘Oh shit – we’ve arrived. We’ve got something to contribute to this society’” – Don Letts

It wasn’t just the black youth who were buoyed by that musical diversification – “It was also a great sense of pride to my parents’ generation,” Letts explains. “They’d come over after the Second World War, to help rebuild the country an’ all that. The way that they tried to assimilate was to deny their roots – deny their culture. They tried to Anglicise themselves, which, to be honest with you, meant they were getting screwed.” The explosion of Trojan Records helped legitimise Jamaican culture across age groups and skin colours – suddenly, even Letts’ parents’ generation could be proud of their heritage. “All of a sudden there was a lot of black acts on Top Of The Pops, for instance,” he explains. “Now, that might seem like a really simple thing, but to my parents, that was like, ‘Oh shit – we’ve arrived. We’ve got something to contribute to this society.’”

Nowadays, it’s impossible to divorce the concept of ‘Britishness’ from that of Jamaican culture – the two are intrinsically intertwined. In the 70s, the early days of that ‘melting pot’ society found an outlet in the skinhead. Today perhaps best epitomised by Shane Meadows’ This Is England, the early days moral and cultural code of that subculture couldn’t be further from the white nationalist stereotype it is now lumbered with. The original skinhead culture was integral to Trojan’s development. “[Trojan] made an album called Skinhead Moonstomp, and on the cover was these white skinheads in boots and braces – they weren’t the racists,” Letts explains. As headlines later began to focus on the less savoury offshoots of the movement however, Trojan’s best intentions – and the Trojan skinhead subculture that evolved out of it – became side-lined in the media’s discourse. “In any large group of people, there’s going to be some dickheads,” says Letts. “Up and down the country, people got the wrong end of the stick.”

“I think it’s by embracing that multiculturalism that we’ll make this country great again. That’s how you make a country great” – Don Letts

It’s a story that has numerous ties to the present day. With the rise of white nationalism threatening inclusive modern culture once more, it seems – sadly – that Trojan’s cultural impact couldn’t have too lasting an effect on society. “I think it’s by embracing that multiculturalism that we’ll make this country great again,” says Letts. “That’s how you make a country great.” That “black and British duality” is something Letts embraces, he admits – it’s also one that Rudeboy charts, the film following that spread of multiculturalism, as that Jamaican influence moved from recording studios to the streets of 70s Britain.

Trojan, through that string of early 70s hits, sowed the seeds of a love affair with Jamaican music that can still be felt throughout Britain today. Modern pop stars like Dua Lipa draw upon dancehall and dominate the charts, while underground British dance genres like dubstep would be nothing without the bass sounds Trojan brought over; everyone from Little Mix to James Blake exhibits elements of Trojan’s DNA. As the label celebrates its 50th birthday, then, it’s important to celebrate that musical impact as much as the political one.

“For the most part, Trojan records were up-tempo, big vibe tunes,” Letts explains, keen to separate the cultural and social implications of Trojan’s wider impact from the dancefloor-filling of the tracks themselves. “They weren’t overtly political, or militant, in the heydays.” It’s that dedication to making something danceable – among all the political and social mire of the 60s – which made Trojan connect, and still sees Trojan records sending the clubs Letts DJs in wild, even today. “Despite all that, Trojan’s been kept alive in the hearts, minds and feet of the people,” says Letts, “Even if the record business collapsed tomorrow, Trojan would live on.”

Rudeboy: The Story Of Trojan Records is out now via Pulse Films