‘Robyn’s oeuvre is the soundtrack to a life lived outside’ – as the Swedish singer releases Honey, Tom Rasmussen investigates her icon status

- TextTom Rasmussen

Go back in time. Fix yourself on the dancefloor, Cheeky Vimto in hand, there, stuck to the carpet of a regional Revolution, screaming in a feelingless lull as the next David Guetta song blears from the speaker which crackles because too many Vodka Red Bulls have been splashed across its wires.

But – what? – it’s not a David Guetta. And suddenly you’re plunged, unwittingly, into your feelings, pulled from the dross of the usual pop banger and into a sound which understands you in a place where nobody ever has before.

You’re necking the drinks, Dancing On Your Own, wiping your slanted fringe from your sweaty brow as you watch the straight man you, now regretfully, spent all those years lusting after as he kisses your best girl-friend, wishing he was kissing you. But, for the first time, it’s almost OK: because this song gets it.

But why does it get it? In short: because it’s a Robyn song. In full: it’s about the position from which Robyn sings.

Usual popular music isn’t usually about the outcast. The very name of the genre decrees that pop music must be popular, ergo most of it contains diluted sentiments about ubiquitous experiences: love, breakups, how much we love our mums. That isn’t to say that pop can’t be rampantly political, but the politics are often communicated via the full package of the star, not by the actual songs themselves.

There are key, and somewhat problematic, boxes a pop star must check if they are to become a gay (male) icon: looks; tours heavily featuring male dancers sheathed in muscle; support of minimum one LGBTQIA+ charity. Extra points for being great on social media, having multiple reinventions, or a vast and varying array of wigs. Indeed, the gay-icon-gay-stan nexus is littered with misogyny and homophobia, but this isn’t for here.

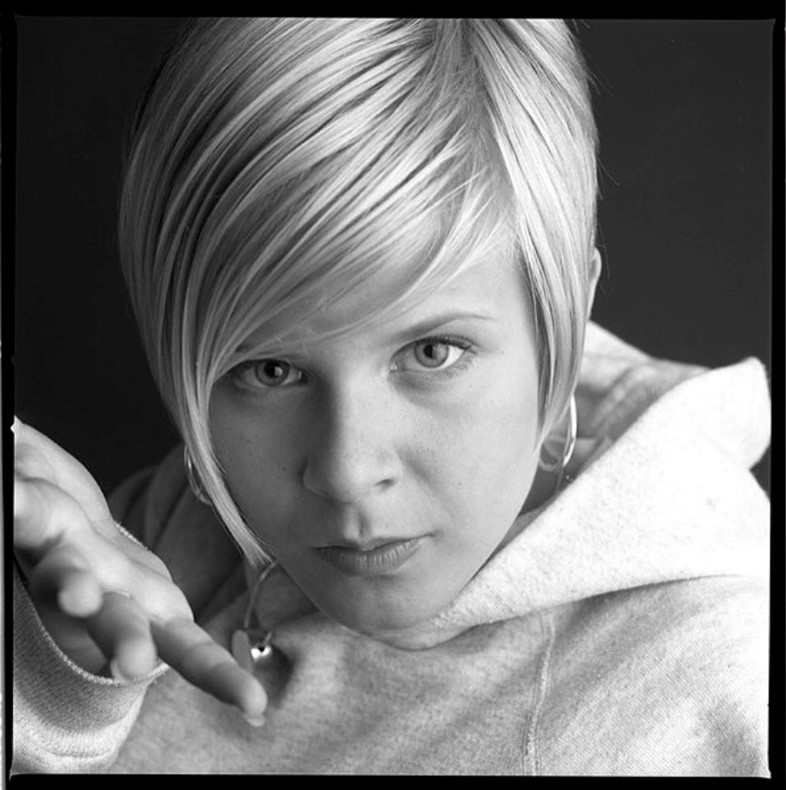

And yet Robyn is a full-on gay icon. In fact, she’s not only an icon of gay status, but of the much sought-after queer status. And yet, remarkably, she checks very few of the aforementioned boxes: she doesn’t really tour, she’s not really got an array of muscle dancers, no wigs in evidence (although she does get points for that edgy bowl cut), and who knows if she’s into supporting charities because she’s not the most active on social media.

For Robyn the icon status is earned by the lyrics, the songs, and the unusual emotions she captures through the viewfinder of the outsider. She gets it.

Robyn seizes the exact tension between the agony, and the ecstasy inside the agony. She sings about niche emotions you can only understand if you’ve stood there, lusting after someone who will never, ever like you back. She writes songs from the position of us, the other – think of Dancing on My Own, Dream On, Be Mine!, Time Machine, Get Myself Together – whilst also demanding that, if you’re lucky enough to score people like us, you’d better be God damn good enough. Remember Who’s That Girl, Handle Me (acoustic, especially), Don’t Fucking Tell Me What To Do, Call Your Girlfriend?

“As a teen, it was music that helped me take ownership of my sadness, the loneliness I hadn’t connected to my queerness yet – listening to her music and strutting into college feeling empowered rather than overwhelmed,” East London queer icon Finn Love extols. “It was club music before I could go to clubs. It’s music about loneliness and anger that isn't sung by a man in an indie band.”

The lyrics and the sound are specific, not generalising, they make you feel like you’ve been seen, like someone else out there gets what it’s like to feel like a total weirdo, to feel lonely, to feel complicated, all while soaring above an orchestra of overtly camp synths.

“Basically, for me, no-one has quite put into words, or music, the actual feelings of unrequited love as well as Robyn,” a friend of mine, who wishes to stay anonymous, gushes over text message. “For myself, as a queer woman of colour, I have been so many people’s experiments, and Robyn puts into words that unspeakable feeling of how it feels to fancy someone who will never fully go for you because you don’t conform to their idea of the perfect, conventional partner. And there’s nothing as healing as being seen by someone else when you’re in that feeling.”

This specificity reaches, also, to where she writes from: heartbreak on the dancefloor, in the midst of rapid time-travel, that liminal agony between best friendship and romantic love. These are the places where queer love lives: behind closed doors, in gazes across a dancefloor, and when, even if just for a night, it finally happens, in other dimensions.

It’s also, arguably, about language: English being her second, and through writing in it at one remove, she manages, prophet-like, to encapsulate an alienation at the heart of every lyric. It’s genuine poetry set to music; it’s feelings first, catchy words second.

And whatever the facts of her personal biography, what’s pertinent is that she knows what it’s like to feel outside, and has from the off (well, after the slight blip that is Robyn Is Here, after which she created her own sound and record label so she could write what she really wanted). One could go into the hard facts of Robyn’s history, but Robyn isn’t facts, she’s emotion. She’s offered so many queers a space to be together in our loneliness, in our separateness. “She’s the only person I want to dance to and cry to at the same time,” Ben Schofield, a friend and fashion editor, explains over a drink.

“Honestly the Body Talk albums have not aged a bit and still bang so much,” music insider Tom Mehrtens explains. “Lyrically her songs are so relatable to the queer experience, the diptych of Dancing On My Own and Call Your Girlfriend is something I think so many queer people can see themselves in. Also Handle Me honestly almost moves me to tears, especially the acoustic version. Finally, the pop fact that she originally sang and released Keep This Fire Burning before giving it to queen of UK soul and queer ally, Beverley Knight, just shows that she had our backs from the get go.”

Robyn intersects many lines for many people, and takes an atypical place in the heart of many queer women, men, and non-binary folk, which is rare when you examine the fan bases of other, indeed brilliant, gay icons who often sit within much stricter gendered lines. Robyn sings about being misunderstood, and for so long we felt misunderstood, with no culture to mirror back what that – being queer, being outside – really feels like. Robyn’s oeuvre is the soundtrack to a life lived outside: one that isn’t trying to take us inside but, rather, exalts the power of standing right where we are, in the corner, watching you kiss her.