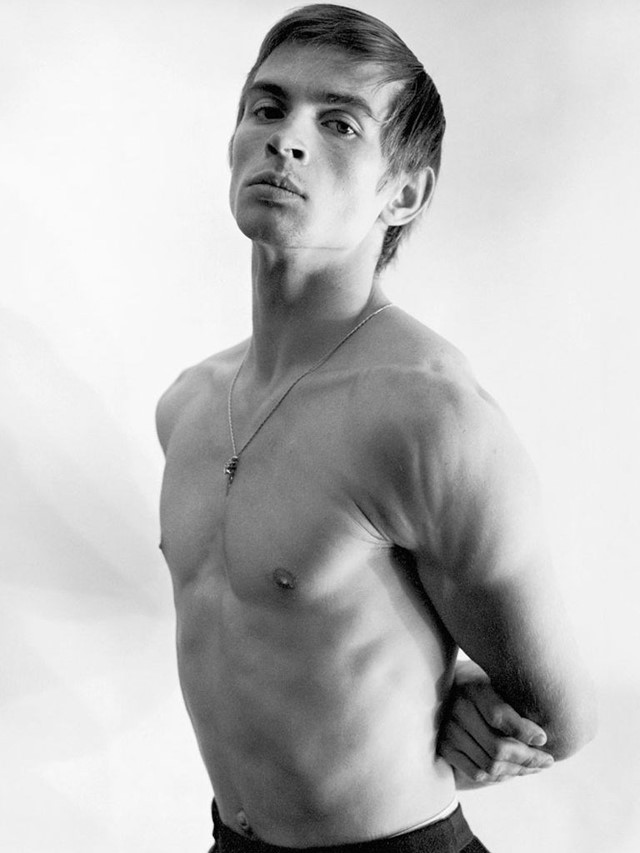

The Story of Rudolf Nureyev, the World’s First Male Ballet Superstar

- TextHynam Kendall

In cinemas from today, Nureyev tells the story of the ‘Brando of ballet’ – watch an exclusive clip from the film here

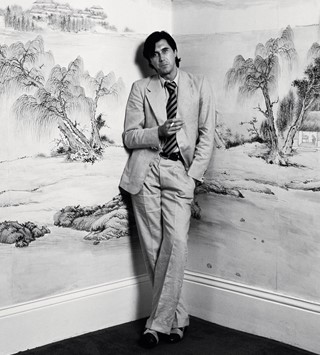

When sibling directors Jacqui and David Morris set out to make a documentary about ballet dancer Rudolf Nureyev’s life, their motivation was not what you might expect. The pair didn’t know a huge amount at all about the dancer – “Only the bones of him” they say during the course of our conversation in Jacqui’s Soho townhouse, which doubles as edit suite and set location for their film projects. The genesis for their documentary Nureyev was, says Jacqui, “Simply the name!” The name? “I knew it was iconic, extraordinary, romantic, epic, loved… but I couldn’t have told you why.”

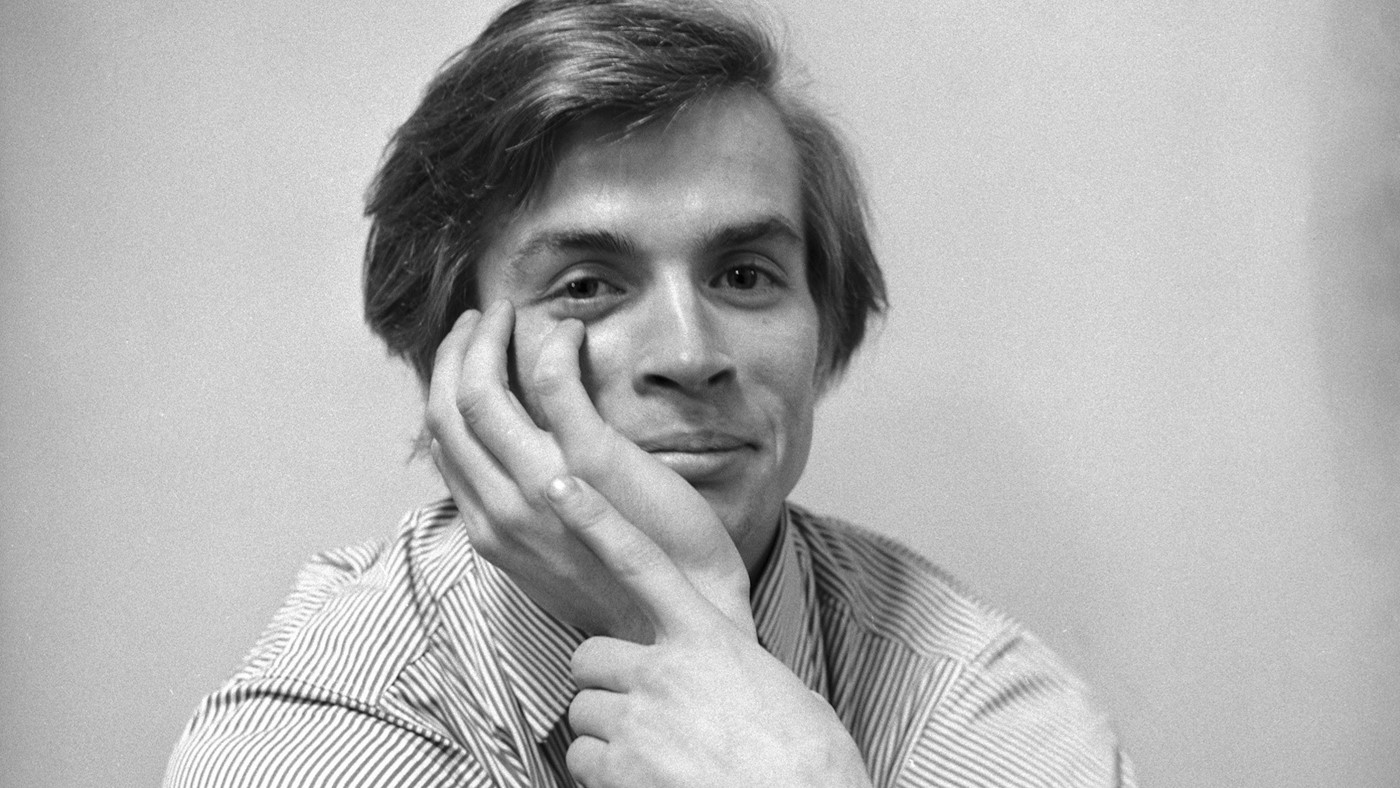

Nureyev was undoubtedly all of those things. He wasn’t technically the best, but he was the first male ballet superstar, paving the way for dancers such as Mikhail Baryshnikov. In a piece of film the directors show me, from the early 1970s, Nureyev sits on a talk show sofa receiving rapturous applause, which lasts – it feels – around five minutes. The show host Dick Cavette turns to the dancer and says, “This is more applause than Mick Jagger got!” And I get it. I want to know why.

First, Jacqui and David approached the Nureyev Foundation, which acts as a centre-point for all Nureyev artefacts, and won them over by screening their previous two documentaries – including the BAFTA-nominated McCullin. As a result, Jacqui and David became the first people entrusted with trawling through the foundation’s enormous archive of video footage. For the most part, this footage came courtesy of Nureyev’s travelling fan base of older women who, enamoured with the dancer, would follow him on his tours, filming from the back rows or from the wings. Much of the footage remained unwatched for years due to the sheer volume of it. The process was long and arduous. In fact, it took the duo two years to complete.

But their persistence paid off. The result is not only a documentary containing around 16 minutes of dance footage that even the most diehard Nureyev fan has never seen, but also a cinematic storytelling unlike any other. Between the beautifully-restored footage and interviews (the final interviews of some participants, who sadly passed since wrapping), the pair have added film of specially commissioned dance tableaux by British choreographer Russell Maliphant. The sequences tell the life story of Nureyev where footage is lacking. It’s not actually been done before in documentary. “Well, if you’re going to be the first cinematic telling of an artist,” says David, “you might as well keep the firsts coming…” Here, the duo tell us more about the making of this film and the ballet superstar.

When you’re finding footage that has never been seen before, do you feel pressure to use it all?

Jacqui Morris: That’s actually a really important question – for us, no. At the end of the day, it’s not a book. You haven’t got the luxury of an audience spending ten hours with the material. You’ve actually got to keep someone’s attention for two hours. To be a filmmaker is to be disciplined.

“During the ballet The Afternoon of a Faun he’s giving a blowjob, you know. Lots of the elderly people from Covent Garden would have been clutching their pearls” – David Morris

What was the most important piece of found footage that you used?

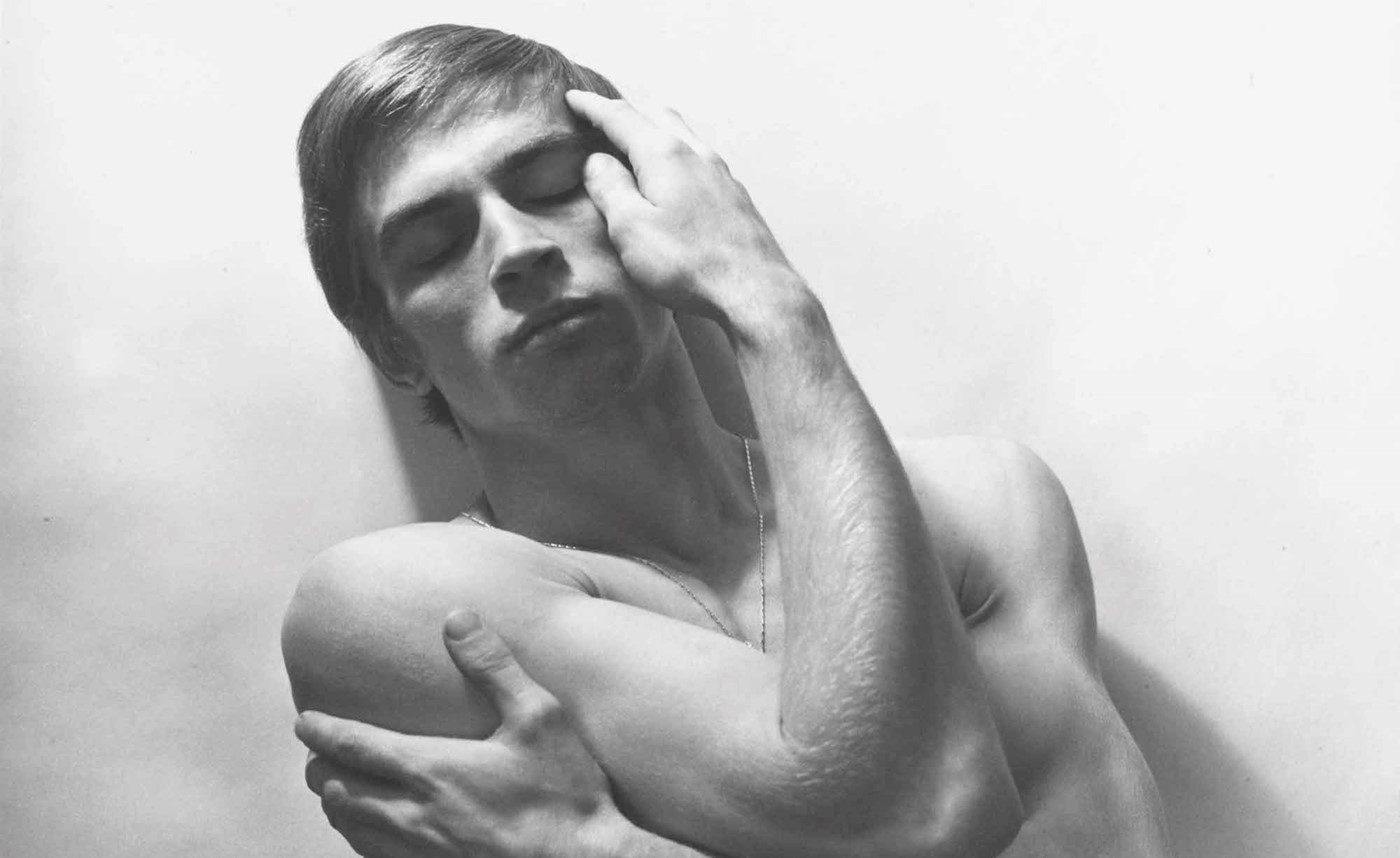

Jacqui Morris: The work that Nureyev did in the 70s with those three important American dance choreographers: Paul Taylor, who sadly just died, Murray Louis, Martha Graham. It’s avant-garde, it’s interesting. Very different to the Nureyev that the audience will have seen. And some of the footage is very provocative, don’t you think? Dancing half-naked…

David Morris: …and sexualised. During the ballet The Afternoon of a Faun he’s giving a blowjob, you know. Lots of the elderly people from Covent Garden would have been clutching their pearls. It’s still provocative now.

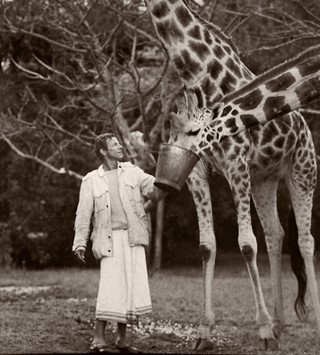

Nureyev is often described in animalistic metaphor, and subsequently his relationships as prey. We can’t dispute the sincerity of his loves, but we can certainly agree that he did benefit from the majority of his conquests.

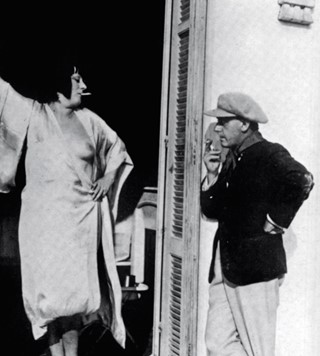

David Morris: In 1961, when Nureyev defected from Russia to the West, managing to seek asylum while on his dance tour in Paris, he went straight for Margot Fonteyn. She was the most famous female dancer in the world. And then, knowing him from bootlegged films he’d seen in Russia, Nureyev went straight after that for Erik Bruhn. He was the most famous male dancer. He fucked Erik, maybe fucked both. So yes he did use people, there’s no doubt about it. What Nureyev really did with people was bring them into his orbit, then once in, he completely dominated them. But he was incredibly loyal to the people who were close to him. I describe him as an Exocet missile… this is somebody who was brought up starving in the back end of beyond, he was so poor that his family would strip the bark off trees to eat. His life was an animalistic fight. And so through circumstance he became a ‘Tartar’ – somebody who was dangerous. Ballet only became his passion because his mother snuck the whole family into a ballet when he was seven, and he was at that impressionable age where he saw on stage a possible means out of there. That was his personality – find a way to survive. An instinctive predator.

“What Nureyev really did with people was bring them into his orbit, then once in, he completely dominated them” – David Morris

In the 70s there was a French choreographer and teacher, Michel Renault, who Nureyev hated. Renault disagreed with Nureyev during a class and Nureyev thumped him, broke his jaw. When he was prosecuted and had to pay 2,500 francs, Nureyev said, ‘If I’d have known it would be so little I’d have hit him a second time!’ So it was also that kind of personality. The Brando of ballet. A beautiful brute.

Were the foundation nervous about how the film would portray Nureyev?

David Morris: No, because they know he could be a bastard. But it also added to the public’s interest in him.

Jacqui Morris: Also, his story was bigger than that. He was bigger than the bad behaviour.

David Morris: He had so little growing up, and was bullied and beaten himself. If you’re brought up in the way he was, you’re literally and figuratively hungry and fighting all the time.

“His story was bigger than that. He was bigger than the bad behaviour” – Jacqui Morris

Regarding some aspects of his story, such as the violence towards women – we would slap, kick and purposely drop dance partners – should we view these things through the lens of the time, or do we have a responsibility to watch it with a more modern, more enlightened viewpoint?

David Morris: It was never good. But interestingly often the people who he was violent towards would come out and defend him, saying, ‘yes, he was violent towards me, but he brought out the best possible performance.’ You’re right in that it’s a mindset of the time and as the storyteller you really have to be careful about how you explain that. You can’t defend him for doing it, but you can’t turn it into a morality tale.

So can – and should – we separate art from the artist?

David Morris: I had this conversation recently regarding Wagner, he was a virulent anti-semite, but his music has lasted the test of time. Is lasting the test of time the definitive answer about successfully separating the two? Because Nureyev’s work has also done that.

“Before Nureyev, male dancers were porters. They were there to hold up the women and only that. It took this fighting man, this animal, this hungry peasant to change ballet” – David Morris

What is the most important way in which Nureyev pioneered ballet?

Jacqui Morris: Well, he gave male ballet dancers a voice!

David Morris: Lady MacMillan, Sir Kenneth MacMillan’s widow, says in the film that before Nureyev, male dancers were porters. They were there to hold up the women and only that. It took this fighting man, this animal, this hungry peasant to change ballet.

Jacqui Morris: And Nureyev proved he was right, proved it by bringing in big crowds to the very end. He was booked in at the Colosseum year in year out, and was doing so pretty much up to his death! (Even if he probably shouldn’t have…) But, you see, it was him that left us hungry for more.

Nureyev is out now