Sawatari Hajime and the Slippery, Secret History of Tentacle Erotica

From shunga to Sawatari Hajime’s new show in London this month, the story of tentacle erotica in Japanese art is a fascinating one – here, Claire Marie Healy shines a light on this tradition, which throws the very nature of the taboo into question

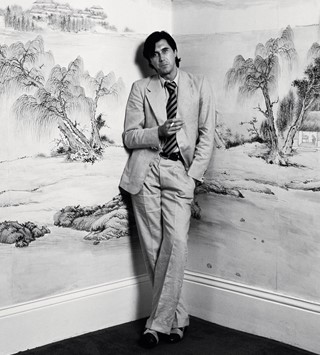

“There is something very sensual about an octopus, whether you like it or not,” says gallerist Michael Hoppen, sitting among a chaotic array of prints and books in his office. “If you’ve got the courage, or if you’ve ever put your hand into a tank and felt one wrap itself around your arm, there’s something very beautiful and sensual about it.”

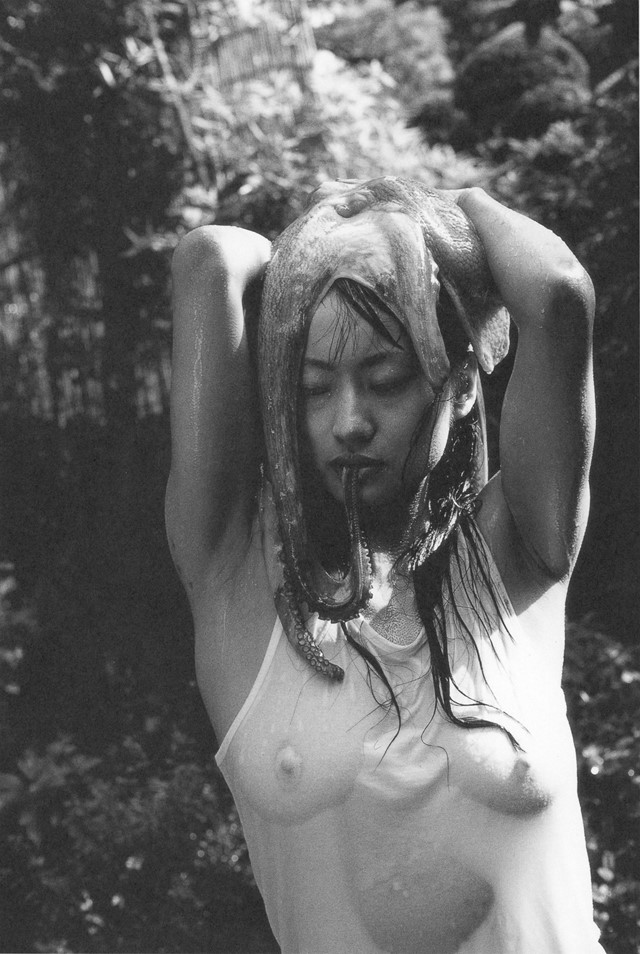

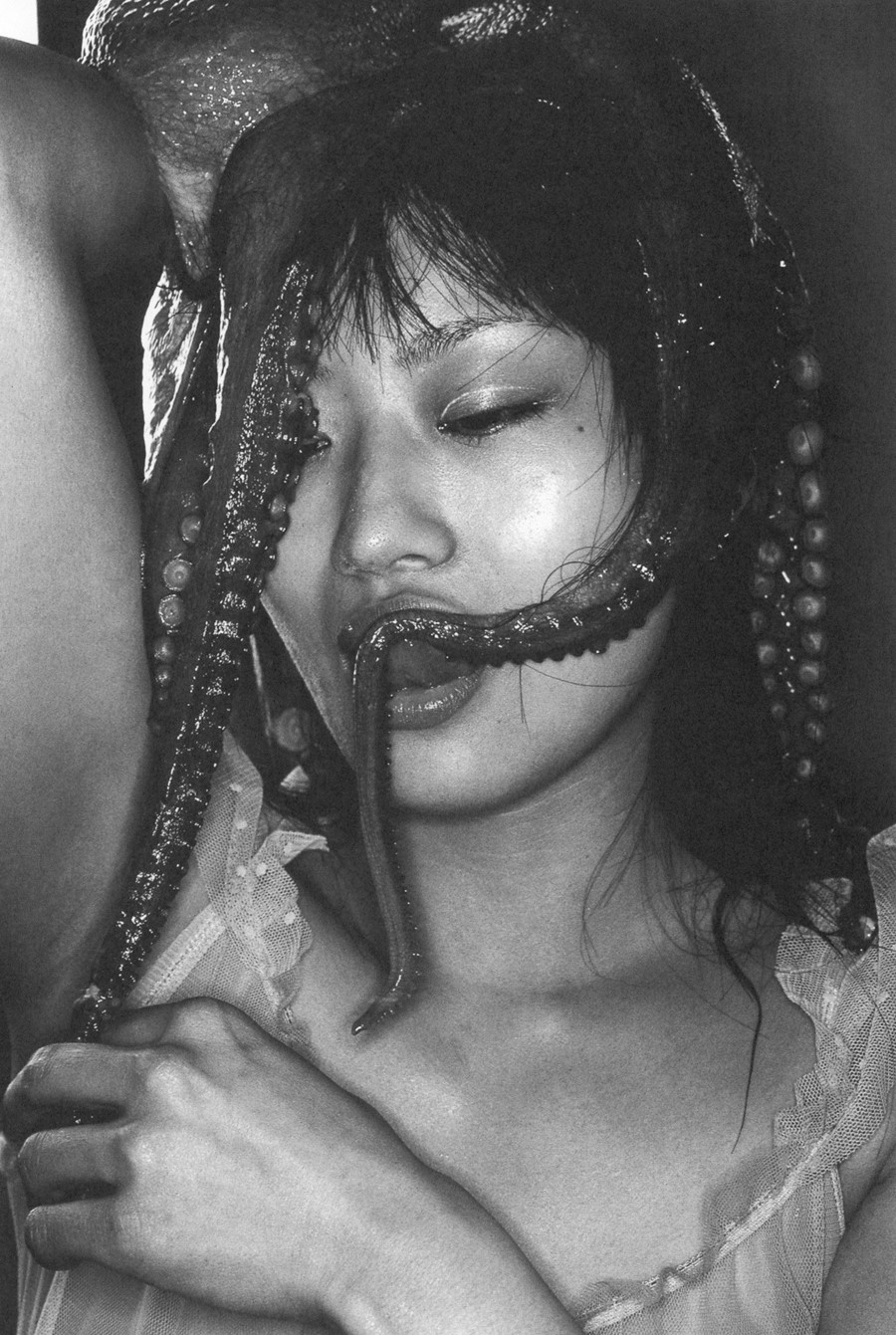

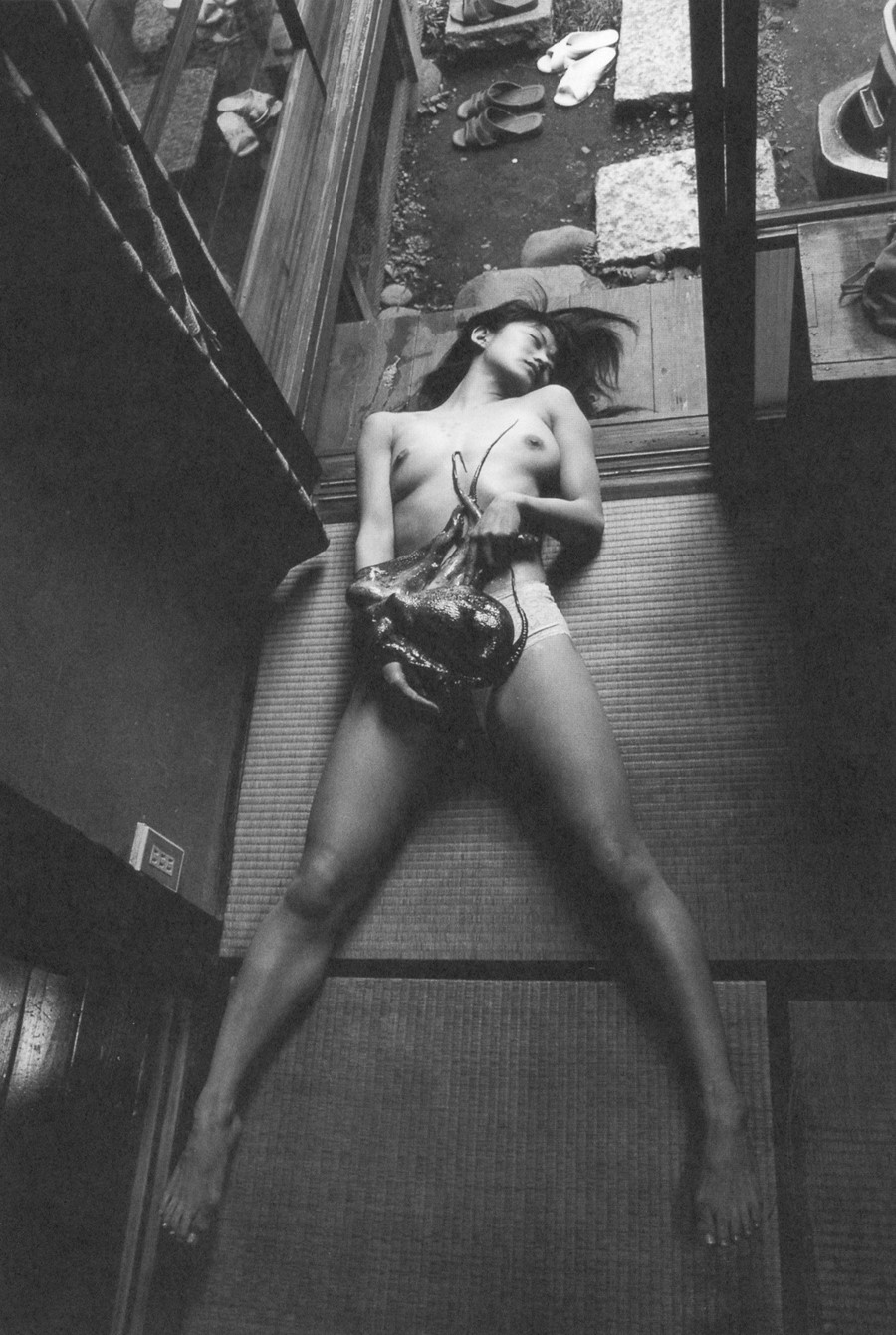

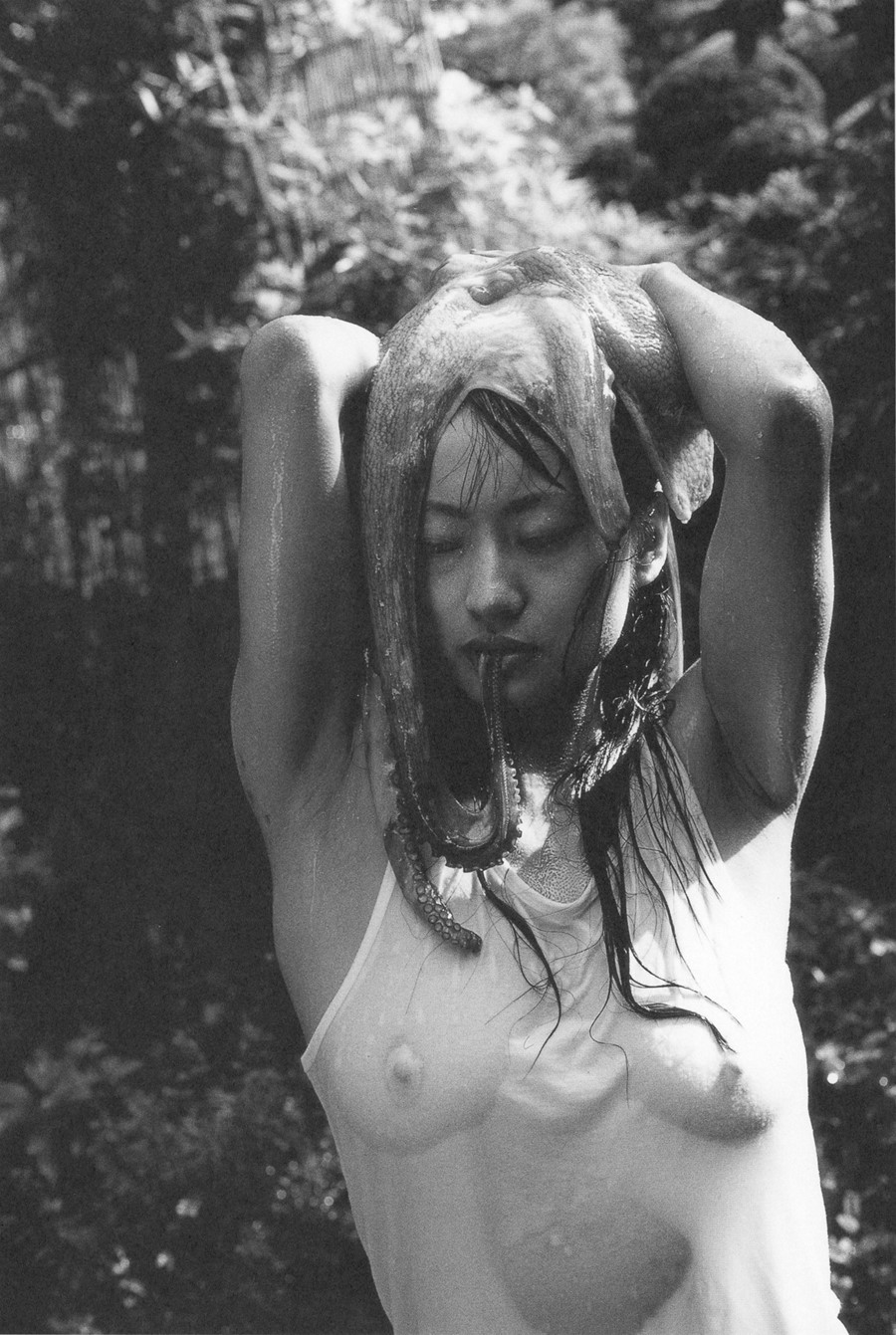

Showing at Michael Hoppen Gallery this month, Sawatari Hajime’s Hysteric Ten photographs tell the story of an octopus, and an actress. Across just eight black-and-white images, these are some of the most confrontational works to have graced London gallery walls this year, but in the context of Japan’s tradition of tentacle erotica, what they confront is more than just standards of taste or sexual mores. These photographs also challenge wider questions about the interplay of fiction and reality, fantasy and the everyday, in all the photographs we consume.

“The fact that these eight-tentacled, nine-brained creatures have slithered their way out of strict censorship and moral codes over the centuries shows the imaginative drive behind our inner lives”

For the curator, whose gallery boasts one of the most important and extensive collections of postwar Japanese photography outside of Asia, his desire to display work of this kind is simply to do with a desire to tell stories, and to showcase the unique way Japanese artists have always told powerful narratives through pictures. “Bringing Japanese work to Europe, as I’ve done for 12 years, is not about bringing just individual, expensive or inexpensive pictures,” he explains, “but about bringing stories (here) so people try and understand a culture through those layers of storytelling. All our artists alive, or no longer with us, in Japan, share that. They are all storytellers.”

Still, it can be difficult to see tentacle erotica as anything but an affront, a strange, slippery interloper that seems alien to our own specific tastes – in a word, the ‘wrong’ kind of story. But contrary to popular belief, contemporary tentacle erotica in Japan shouldn’t be seen as confirmation of a country’s bizarre sexual tastes. Ironically, one reason tentacle erotica has emerged in modern Japan as a source of pleasure at all, in popular manga or the hardcore hentai genre, has been the country’s dated censorship laws. Article 175 of Japan’s penal code – known colloquially as the Obscenity Law – bans any person from distributing, selling or displaying an obscene document or image in the first place, and the genitals of any man or woman have to be pixellated out. There’s an argument that the more extreme sexual narratives of Japan’s visual culture have actually been borne out of this censorship, with, for instance, tentacles replacing the necessary bokashi (fogged) genitalia. Thus, in a hyperactive visual culture at once heavily censored and sex-drenched, the octopus’s erotic potential has wriggled through this double standard.

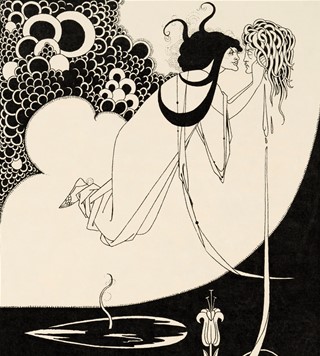

But for Hoppen and Sawatari, Hysteric Ten should be seen in-conversation with older forms of image-making, not the kind of tentacle erotica one might find in hidden corners online or on manga store shelves today. In early modern Japan, between 1600 and 1900, thousands of sexually explicit works of art were produced and circulated. Known as ‘spring pictures’, or shunga, the works were created by artists of the ukiyo-e school, translating as “pictures of the floating world”. Created through ink paintings and woodblock prints – applied to hand-scrolls and mass-produced illustrated texts – sexually explicit artworks were designed to be viewed in book form, to be shared between couples or friends in the privacy of the home. They were, importantly, anything but taboo – owned by men and women (who were often gifted prints on their wedding nights), they were a source of laughter and pleasure that transcended the constrictions of class and gender in public society. What’s more, they were painted by some of the era’s greatest artists, including Kitagawa Utamaro and Katsushika Hokusai. It was the latter who created art history’s enduring statement on the octopus as erotic counterpoint: in Hokusai’s infamous woodblock print, ‘The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife’ (1814), an entanglement between a woman and two octopuses is depicted. (In translation, the written notes that line the backdrop controversially indicate that all parties are pleased).

“In (Japan's) hyperactive visual culture, at once heavily censored and sex-drenched, the octopus’s erotic potential has wriggled through this double standard”

While Hokusai might be the most famous image-maker of tentacle erotica – recently, you may have seen it on Peggy Olsen’s office wall in Mad Men, or in Park Chan-wook’s twisted, sexually charged The Handmaiden – his rendition was not the first. Inspired by a popular Taishokan Buddhist fable, in which a female diver steals a pearl from a palace at the bottom of the sea and is pursued by various creatures, other contemporaries produced shunga that depicted their own octopus fantasies in the same time period. But by the turn of the century, with the dawn of the Meiji period, the wholesale importing of Victorian views on modesty meant that shunga was officially designated an obscene remnant of the past. This influx of western morality endures to the present day: for proof, note how the British Museum’s unforgettable shunga show in 2013 was refused by ten Japanese museums before the Eisei Bunko Museum finally accepted it in 2015, and yet any visitor to Tokyo will note the very public face of explicitly sexual manga. It’s within this contemporary landscape, with strange double standards on explicit content, that a photographer like Sawatari is making his photos. “As regulations are gradually becoming stricter also in Japan, there are in fact quite a lot of photographs that I’ve shot but never exhibited,” the artist admits, writing over email.

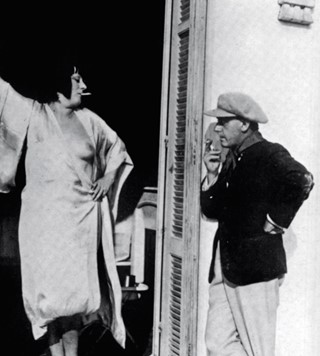

Shunga has long fascinated artists in the west, too, with works of tentacle erotica making their way into the collections of 20th-century Japanophiles in Europe and into the artwork of figures like Rodin and Picasso. The latter publically rejected shunga in public, including in front of avid collectors Gertrude Stein and Apollinaire. But he maintained a private collection and, as shown in Tate Modern’s current show Picasso 1932, he was undoubtedly inspired by Hokusai’s fantasy as well as potentially the underwater filming of octopuses by French filmmaker Jean Painlevé, influences which mixed to result in his “Reclining Nude”, transforming mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter into a bulbous, multi-limbed alien.

Unlike these artists, Sawatari’s photographs shock because they are just that – photographs. We feel that a real woman has encountered a real octopus in these images; we can almost feel the suckers on our own skin. And yet the artist is not alone in this approach. The late Ren Hang, whose bright architecture of limbs interacting with nature were fuelled by his activism for freedom of expression in China, sometimes photographed his nude female subjects with octopuses, covering their faces with their slimy limbs or picturing them eating them off a plate. Ai Weiwei, an early advocate of the photographer’s, paid tribute to Hang’s East Asian sensuality in Time magazine in 2014, saying, “In Chinese literature or poetry, sex is about something which is impossible. It’s very different from the west. It’s sexier.” Also no stranger to controversy, famed provocateur Nobuyoshi Araki’s Tombeau Tokyo featured sex dolls and toys amid floral compositions, like a perverted Dutch masterwork – and also sees a female model taking a bath, cheerily, with an octopus.

“Taboos are things that change with the times, and that are handled differently in different countries or regions in the first place. I think of my work as a constant operation on the brink of rule violation… it’s just that the things that I’ve been pursuing from the beginning came to be tabooed at certain times and places” – Sawatari Hajime

In the USA, one famous Herb Ritts-lensed series comes to mind, in which a future Academy Award nominee, Djimon Hounsou, is depicted with a dead octopus on his head. In Ritts’ hands, it becomes an image of surrealist, otherworldly beauty, but the actor was somewhat understandably anxious at the shoot concept, according to reports. This is worlds away from Sawatari’s actress-subject in Hysteric Ten, who is a regular collaborator of the photographer’s, and complete partner in the project’s concept. “I was simply convinced that she was spirited enough an actress to embody that idea of ‘being entangled with an octopus’ that I was having in mind. It’s something that people don’t normally like to do, (but) she played the part with the pride of a professional actress,” describes Sawatari. A woman’s role in any rendering of tentacle erotica is often charged with the misogyny so pervasive in sexual imagery, of course. (It’s worth noting that, in manga circles, some female artists are reclaiming the genre and bringing out its potential to empower women.) But Hysteric Ten, which in the original book also includes a wider, more demure series of portraits of the actress, seems an equal collaboration between artist and actress.

“Whatever their degree of ‘realism’, all photographs embody a ‘romantic’ relation to reality”, wrote Susan Sontag in an introduction to Peter Hujar’s Portraits in Life and Death. The encounter might have been real, but the performance in Sawatari’s images is a fantasy; the images, and what they make you imagine, a fiction. And while Hysteric Ten might confront a taboo, taboos are always relative, as the photographer explains. “Taboos are things that change with the times, and that are handled differently in different countries or regions in the first place,” he says, bringing to mind the journey that tentacle erotica has undergone in the public perception, from ancient fables to shunga and the contemporary pornographic landscape in Japan. “I think of my work as a constant operation on the brink of rule violation… it’s just that the things that I’ve been pursuing from the beginning came to be tabooed at certain times and places.”

For Hoppen’s part, he wants people to remember that the use of octopuses in erotic scenarios are a straight shot to the realm of fantasy – in some ways, no more or less than that. The fact that these eight-tentacled, nine-brained creatures have slithered their way out of strict censorship and moral codes over the centuries, simply shows the imaginative drive behind our inner lives. “We all have things that drive us, that turn us on and turn us off,” says Hoppen. “I think some of those things are kept private and some are very public. But I (do) think people need to operate within fantastical imaginations.”

“In my view, the essence of a poem is not in the letters, but it’s in the spaces between the lines where the actual poetry unfolds. This is perhaps a very Japanese kind of sensibility” – Sawatari Hajime

In a biography of Picasso, Roland Penrose writes of the artist’s wife, Olga, that “a woman seated in a chair could resemble the convulsed tentacles of an octopus”. That less-than-flattering image makes us question what should really be taboo, or unallowable, in art. Somehow, contorting the image of a woman’s body into the shape of an octopus – transforming her body into a symbol of mingled male fear and admiration – seems more offensive than having her model with one.

Either way, between the devil and the deep blue sea, tentacles in art continue to fascinate. For Sawatari, the beauty is in the gap of understanding that occurs when these images are viewed: that space where you’re like, ‘What do I think about what I’m looking at?’ “In my view, the essence of a poem is not in the letters, It’s in the spaces between the lines where the actual poetry unfolds,” he says. “This is perhaps a very Japanese kind of sensibility.”

Sawatari Hajime is at Michael Hoppen Gallery, London SW3 3TD, September 24–October 15