Guillaume and Jonathan Alric discuss how the work of photographers Josef Koudelka and Robert Doisneau has shaped their work

- TextTom Connick

In a few short years, two cousins have become one of music’s most talked about acts, lauded for their beautiful and profoundly moving videos and their unique brand of electronic music that has been known to reduce its listeners to tears. Today, Guillaume and Jonathan Alric – better known by their stage name, The Blaze – release their highly-anticipated debut album, Dancehall. To coincide with this exciting moment, the enigmatic pair have taken over the Another Man website, presenting a series of five articles that shine a light on their extraordinary work.

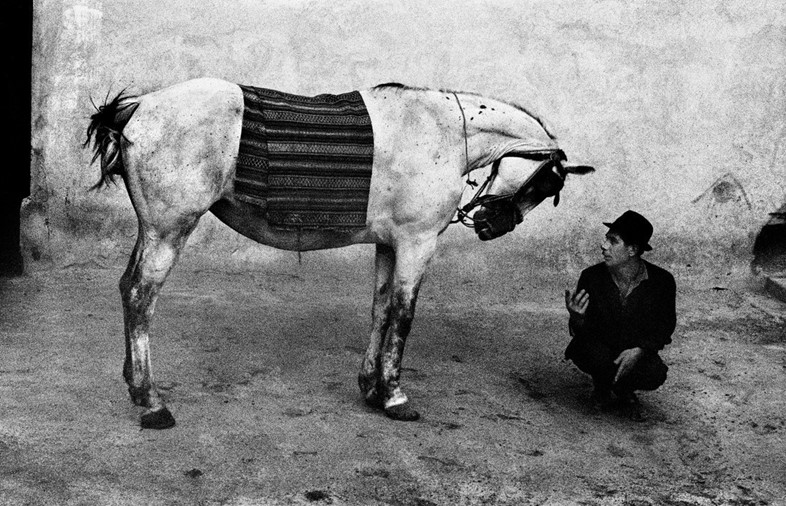

The Blaze’s latest music video, Queens, which is arguably their most emotionally intense offering to date, is a raw portrayal of life and death in a traveller community. Inspired in part by the duo’s own time spent with travellers, the video is also a nod to Czech-French photographer Josef Koudelka, and the impact his humanist photography has had on their own art.

“He did these very long works about gypsy people in the 70s,” explains Guillaume. “He did this work for ten or 20 years. We love this guy because he would go and live with them completely – he really gave himself for his work. That is what we try to do. It’s very honest, in a way, to research humans and to be with them.” That sense of immersion in a foreign culture is integral to The Blaze’s work – it’s a humanist approach that can be felt through Dancehall and its accompanying visuals, but one which really took root in the pair’s early, pre-Blaze experimentation with photography.

As a teenager, Guillaume worked in a photo lab’s dark room; even today, he quickly recalls a moment where Koudelka’s personality really impacted his own. “One day Josef Koudelka came in [to the studio]. He just arrived and immediately started giving vodka to everybody! He invited everybody for a drink. I was young and just thinking, ‘Wow, that guy is like his photography – he’s really human.’ He gave everything.”

Jonathan also cites another humanist photographer as key to their artistic inspirations – Robert Doisneau who, with Henri Cartier-Bresson, was a pioneer of photojournalism. “I was watching a documentary about him a week ago, and I didn’t know that all his photos were mise-en-scène,” he explains, “Made up, you know?” Ostensibly capturing moments in time and chance interactions between humans, Doisneau’s works are actually carefully constructed and feature models, rather than everyday citizens, in a number of seemingly everyday situations.

It’s that delicate balance between real life and fantasy that can be felt through The Blaze’s own experimentations with visual mediums. “I thought it was a moment that the guy was really lucky to witness, and be there to take the photo, but no,” Jonathan continues. “He asked the couples to be there, and they are actors – the photo is not true, but it seems to be true. That’s why it is a good influence for us – this guy tried to catch very poetic moments, and he’d do it in a way that was really inspiring for us; the construction of an image.”