Leigh Bowery, Ulay and Man Ray join contemporary artists at the Hayward’s new show – but can photographs and prints can ever really do this subversive art form justice?

- TextAmelia Abraham

When I first heard about The Hayward Gallery’s new DRAG exhibition, my first thought was: “Finally, a queer British art show for 2018”. Last year, as Britain celebrated the 50th anniversary of the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality, galleries across the UK hoisted their rainbow flags into the sky and encouraged LGBTQ+ audiences through their doors, with shows like Queer British Art 1861–1967 at Tate Britain, and Coming Out at The Walker in Liverpool. For queer art history geeks, it was like all our Christmases came at once, but then, towards the end of the year, enthusiasm waned, and it began to feel – to me, at least – like our moment was passing. As though, next year, Christmas might be cancelled.

I thought I was the only person who felt this way, but when I arrived at the private view for The Hayward’s DRAG show on Wednesday, the hundreds of people queueing for entry suggested that I wasn’t. A colourful crowd, particularly against the brutalist backdrop of the Southbank’s grey walkways, the line was littered with drag queens and outsider artists, some of whom told me they were excited to see drag portrayed within the four walls of a British institution. But as we headed inside, a problem emerged: the show itself – full name: DRAG: Self-portraits and Body Politics – was simply too small to house so many people.

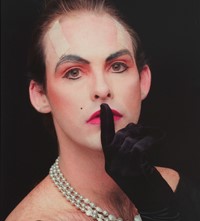

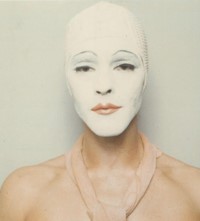

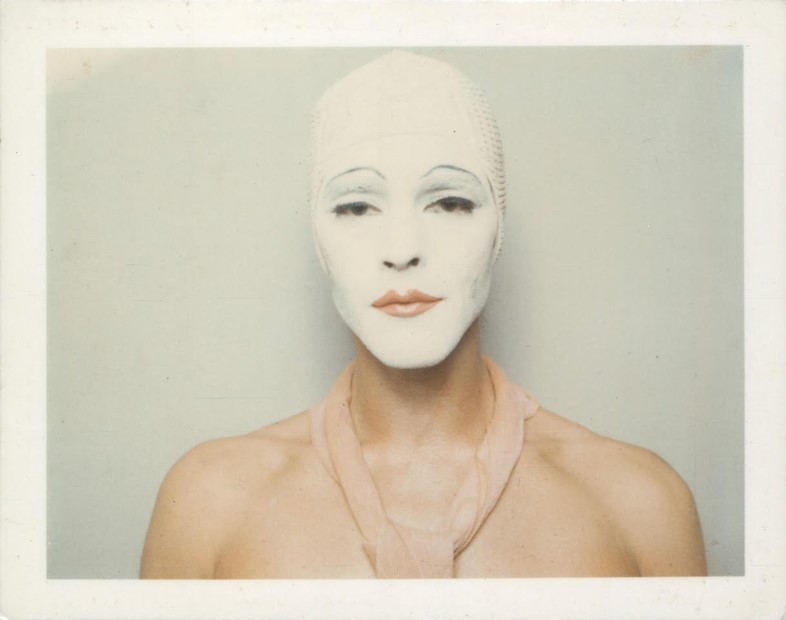

In the one-room gallery space dedicated to a show that featured over two dozen artists, curator Vincent Honoré had squeezed in 60 years of drag history. All the greats were present: on a wall of video works, a film of experimental drag legend Leigh Bowery played on loop alongside Paul Kindersley’s early prototypes of the YouTube makeup tutorial, alongside a video by contemporary performance artist Victoria Sin. In the middle of the room was Renate Bertlmann’s sculpture of a dildo wearing a dress, just visible through the teams of people. Ulay’s work was there, and Man Ray, and David Wojnarowicz, all lumped together with no particular chronology and without context.

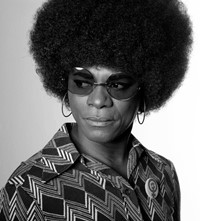

Some complained of a lack of focussed curation. But to me, the randomness and the broadness worked. If drag hinges around the subversion of gender norms, traditionally defined as “clothing more conventionally worn by the opposite sex, especially women's clothes worn by a man”, it has become so much more than that in recent years, as the popularisation of drag has spawned more types of it; drag kings, ‘bio queens’, drag girl bands, performance artists pulling elements from drag and the downright weird and abstract. Here, I thought, the full spectrum is truly on display, and importantly, the curation shows us that the multiplicity has always been there.

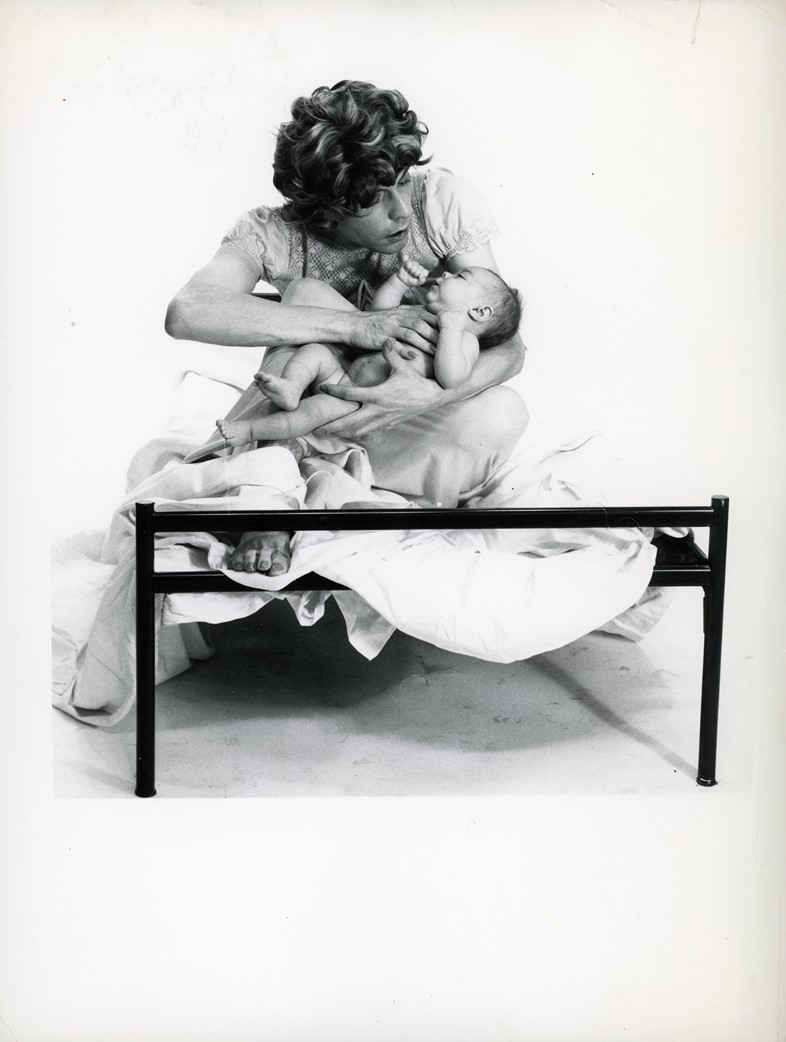

Yes, drag is about gender, says DRAG the exhibition – as you walk in you’re greeted with the Ana Mendieta photographs of her plastering facial hair to her face – but there is also Cindy Sherman’s character drag, or the work of Lynn Hershman Leeson, who embodied her alter-ego Roberta Breitman for around four years, blurring the lines between fantasy and reality. Seeing Leeson’s work in this context immediately makes me think of the RuPaul quote, “We’re born naked and the rest is drag” and the wider show seems occupied with this idea too, asking: What constitutes drag? Where is the boundary? Are we doing it all of the time?

This isn’t the first time drag has been celebrated in the gallery space; all of the featured artists have been successful in their own right (early member of ACT UP Hunter Reynolds had a big solo show at Hales Gallery just last month), the 2016 Berlin Biennale was titled “The Present in Drag,” and so prominent is RuPaul’s Drag Race that Whitney Biennale curator Christopher Lew named it as a key influence for the show in 2017. I couldn’t help but wonder whether this popularity played a role in the Hayward’s decision to organise the show, or in how many people turned up. But more interesting than how many people care about drag now, is how its popularity changes the way that we see the images. And this is at the crux of why the new show feels relevant. In an age where RuPaul puts drag on primetime TV globally, do we still find the sight of Pierre Moliner or Robert Mapplethorpe in drag shocking or subversive?

DRAG: Self-portraits and Body Politics is a must-see exhibition, but overall I felt a little shortchanged, mostly the compactness, but also how the lack of context disappointed the queer art history geek in me and only seemed to speak to the idea that now drag is a quick throwaway; something to glance at on Instagram rather than a resistant or subversive art form in context of everything it stood in opposition to at a time when we weren’t quite so open about gender or sexuality. And of course, drag is, in its essence, a mode of performance, prompting the question of whether photographs and prints can ever really do it justice. The opening night only really came alive when performance artist Adam Christensen came and set the space alight with his accordion performance.

The question of ‘what is drag’ is an exciting and prescient one, but personally, I feel I already know the answer: drag is visceral, noisy, in your face. Go and see the exhibition, yes, but for God’s sake go and see some real drag too.

DRAG: Self-portraits and Body Politics is at the Hayward Gallery until October 22