Claire de Rouen’s director, Lucy Kumara Moore, provides a short introduction to the masterful Japanese culture of book production

The history of 20th century Japanese photobook publishing is a history of beauty, gravitas, technical brilliance and preternatural creative experimentation. It’s also one that reflects this period’s broader political and cultural history: trends in Japanese photography mirrored and responded to major events, with WW2 marking a watershed, and it was often an expression, also, of dialogue and exchange between East and West. Early 20th century Pictorialist photography, for example, assimilated the aesthetics of both Japanese and Western painting in order to create soft-focus, carefully composed photographs that aspired to take the medium beyond that of merely reflecting of reality. Later on, Daido Moriyama’s ambulatory process of recording in an indiscriminate, freewheeling way the quotidian unfolding of his life paid homage to Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (1957) and William Klein’s Life is Good and Good for You in New York (1955) as well as the haiku poems of Basho.

The Japanese culture of book production – editing, sequencing, layout and printing – is masterful and longstanding. When I reorganised the shelves of Claire de Rouen a few years ago, ordering the books alphabetically instead of by country, I kept the Japanese section intact as a way of honouring this brilliance.

One of my favourite stories about book making involves a fashion catalogue in the process of being designed and published in the UK but produced in Japan: halfway through, an elderly Japanese woman telephoned the publisher and asked why silver not matt black staples were being used for the binding. The smallest things make all the difference with a book.

Japanese photography does it all, from Kiyoshi Koishi’s austere abstraction, Daido Moriyama’s jazzy frenzy and Nobuyoshi Araki’s vivacious eroticism to Kishin Shinoyama’s glossed-up pop sex, Rinko Kawauchi’s poetry and Masahisa Fukase’s mournful allegory. Here is a short guide to Japanese photography and photobook publishing, as told through five crucial works.

Early Summer Nerves by Kiyoshi Koishi

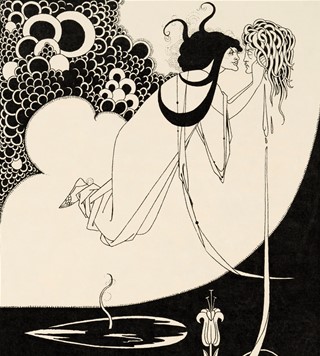

An important work of pre-war Modernist Japanese photography, Early Summer Nerves was released in 1933 and is now in the collection of the British Museum, no less! Much later, in 2005, a facsimile was published by one of my favourite imprints, Nazraeli Press, which is based in California. Published in an edition of 100 numbered copies, Nazraeli’s Early Summer Nerves has sleek zinc metal covers, just like the original. On the front, snazzy black graphical shapes evoke the collage techniques being put to use in the artistic avant-gardes of the 1930s. Inside, a series of full bleed black and white plates are printed onto heavyweight paper. There are only ten images in the book: this is a less-is-more scenario which the Japanese do very well.

Koishi draws on the photogram, solarisation and photomontage techniques of László Moholy-Nagy and Man Ray to create abstract images which are combined with poetic fragments of text. Images of the natural world are layered with streaks of light or the inverse shadow of a coiled spring: Koishi’s works evoke an emotional response to new experiments in science and technology. Before WW2, quantum mechanics – with its description of light as a photon, or discrete package of energy – had not acquired the horrific connotation of post-Hiroshima Japan, but was one of many radical new ideas.

Farewell Photography by Takuma Nakahira and Daido Moriyama

Published by Syashin Hyoron Sha in 1972, Farewell Photography represents a major contribution to postwar Japanese photography and photobook publishing. Both Daido Moriyama and Takuma Nakahira were part of the Provoke group of photographers based in Tokyo in the late 1960s, named after the experimental, and highly influential magazine of the same name (which had a short-lived run from 1968-70). In the aftermath of the war, Provoke photographers practised a subjective, expressive approach to image-making that was at odds with the dominant commercial and documentary imagery of the time – that in fact, involved a complete break down of traditional aesthetic principles.

In this way, a new language of photography evolved in response to the fraught politics and disrupted nationhood of this time. Farewell Photography sees Moriyama producing high contrast and abstracted images inspired by the free-flowing rhythmicality of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and its message of rebellious spirituality. Now almost 80, and with hundreds of books to his name, Moriyama’s photographs have a contrapuntal energy, capturing many things at once in a single frame. Nakahira was cofounder of Provoke, and played a central role in establishing the are-bure-boke style of photography (grainy, blurry and out-of-focus).

Midori by Nobuyoshi Araki

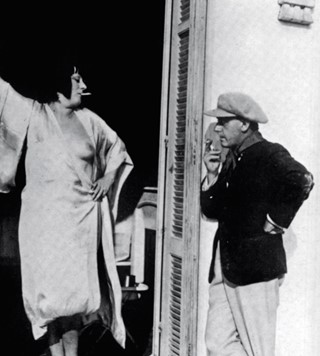

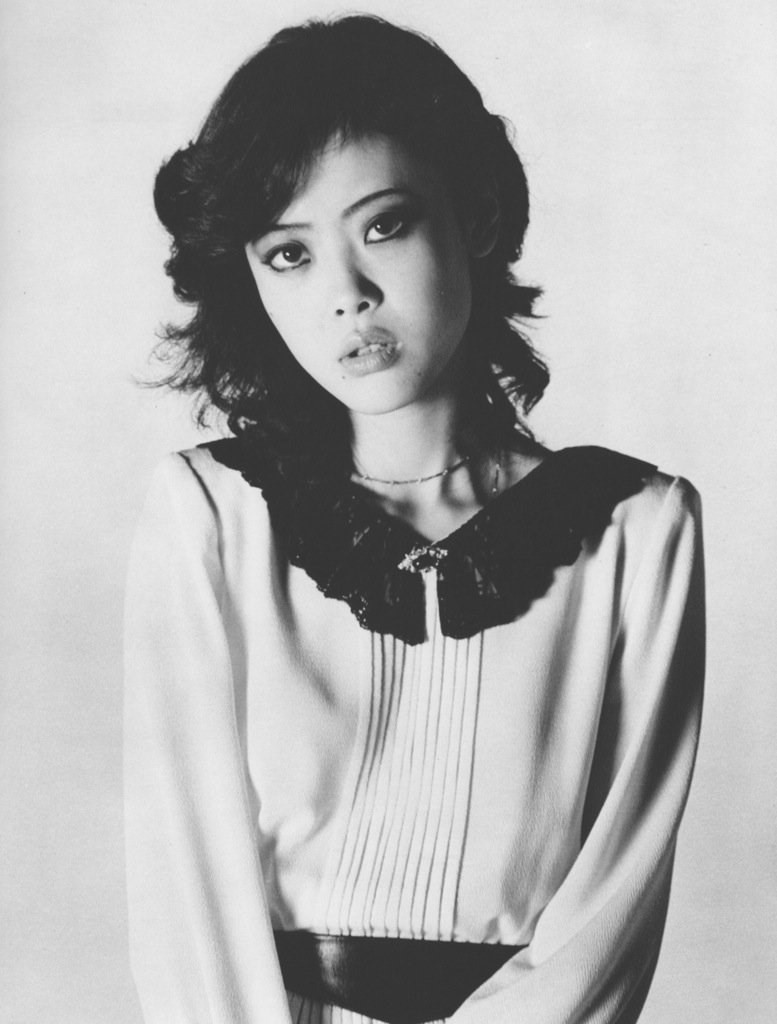

This is not Araki’s most famous or most important book – which might be Sentimental Journey, the document of his relationship with his wife, Yoko, which he self-published in 1971. But Midori is one of my favourites. First thoughts of Araki are often of sexually-explicit, high-octane colour visions of naked women in bondage, toy dinosaurs and suggestive flowers (which I love, by the way). But his work is anything but one-dimensional and in Midori, a series on the daily life of a young woman employed in a Japanese bathhouse in Yoshiwara, Tokyo, the tone is decorous not raunchy.

The book’s emotional pitch oscillates between serenity and melancholy: the title is taken from a 19th century novel about the younger sister of a bathhouse girl – which concentrates on the chapter of her life just before she takes on this role, too. Araki’s subject is given a fictional name, not her own. In this sense, perhaps, she is inappropriately romanticised. But she is undeniably beautiful – and her gaze is strong. Published in 1982, Midori is one of the rarest of Araki’s books.

Rasen Kaigan (album) by Lieko Shiga

Shiga’s book was published in 2013 so I am breaking the rules a little, but I wanted to include a contemporary woman in this list and the spiritual and oneiric overtones of Rasen Kaigan (album) connect it back, in my mind, to the expressionistic approach of the Provoke photographers. The title means ‘Spiral Coast’, and refers to Kitakama in the Miyagi Prefecture of Japan where Shiga began a residency as the village photographer in 2008, recording the rituals and religious events of the coastal community there. In 2011 Kitakama was badly affected by the tsunami and Shiga lost all the work she had made there prior to this natural disaster.

Rasen Kaigan is Shiga’s response to the event in which a significant number of the village residents lost their lives: dizzy, psychedelic-coloured photographs taken at night or in the half-light with distressed analogue cross-processing and double exposures. Pictures of scarred or scorched looking beaches, blankets strewn across the ground, leafless trees and groups of people gathered in communion amount to a constructive and poetic response to tragedy. One of the theories of the capabilities of photography that I find most compelling is German writer Walter Benjamin’s concept of the ‘optical unconscious’ – a term he coined in 1931 to suggest the capacity of photography to reveal the unseen – a kind of inner reality usually hidden from the naked eye. To me, this is what Rasen Kaigan achieves, and beautifully so.

Ravens by Masahisa Fukase

Repeatedly described as a major contribution to the history of photography, Fukase’s Ravens was initially published in 1986 and the first edition, long out of print, is now worth a fortune. It gathers together a decade’s work, through the course of which Fukase became increasingly obsessed with documenting unkindness-es of ravens in rural and urban Japan. They appear as patterns of opaque shapes across a dark sky, or silhouetted, ominous individuals, as prehistorically-clawed beasts or elegant and fugitive characters in fading light.

Ravens could be thought of as an interrogation into photography’s relationship with light and dark: everywhere in this project the image seems to suck the viewer into a closed, otherworldly space that is invariably dimmed. It is also an unrelenting allegorical proposition – Fukase calls upon the raven, as a symbol of foreboding, to express both his own trauma (his divorce left him scarred) as well as those of his country, post-Hiroshima. A new edition was published by MACK in 2017.

Lucy Kumara Moore is director of Claire de Rouen, as well as a curator and writer