Bosch’s Monsters Explained

- TextAlex Denney

To coincide with the release of The Curious World of Hieronymus Bosch on DVD, the documentary’s narrator shines a light on some of Bosch’s more bizarre creations

“Poor is the mind that always uses the inventions of others, and invents nothing itself,” reads the text above a brooding sketch featured in The Curious World of Hieronymus Bosch, David Bickerstaff’s new documentary about the pre-Renaissance painter.

Clearly, this was never going to be an issue for Bosch. Medieval works of art teem with images of heaven and hell, but the Dutch master’s inventions transcend the merely moral to inhabit a world of pure imagination, one that found a modern-day mirror in the work of surrealists like Dalí and Leonora Carrington. His work offers a tantalising glimpse into the medieval mindset, while speaking to our own hopes and dreams with a power that’s undimmed some 500 years after they were created.

“Bosch’s imagination is deeply rooted in the vocabulary of the medieval world, but what he does with it is carry it further so that it does become strikingly modern,” says The Times art critic Rachel Campbell-Johnson in the film, which reveals the painter as a respectable society figure far removed from the crazed eccentric of popular renown. “[He’s] the first artist who truly paints the imagination.”

Still, it’s apt to look at some of his more bizarre creations and wonder, ‘What on earth was he thinking of there?’ To answer that question, we spoke to the documentary’s narrator, artist and filmmaker David Bickerstaff.

St John the Evangelist on Patmos

Bosch’s depiction of St John brainstorming the Book of Revelations with the Virgin Mary contains one disconcerting detail – a small insectoid creature at the martyr’s side. “The strange creature with a cauldron on his head and arrows in his belly is thought to [be] a self-portrait of Bosch, but there is no direct evidence of this,” says Bickerstaff. “The same face with glasses appears in some of Bosch’s other paintings, which has led to the speculation. Medieval and Renaissance artists often used their own portraits in their work. Bosch had an incredibly rich imagination and he was taking individual elements from a variety of sources and putting them into paintings in new ways. The meaning and purpose of this creature is speculative, but there is an element of religious sacrifice shown through the arrows, which lead to the receiving of the Holy Spirit – the ‘cauldron of fire’ imagery. Bosch was a religious man and often used visual metaphors to portray a message to the medieval world.”

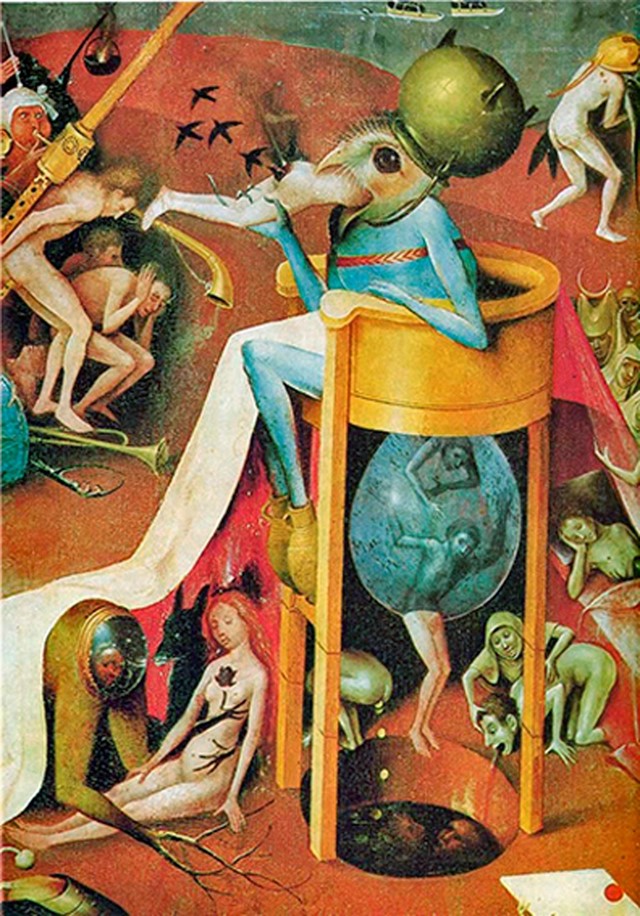

The Temptation of Saint Anthony

According to his biographer, Athanasius, St Anthony was plagued by all manner of beasts in his longstanding beef with the devil, including wolves, lions, snakes and scorpions. Oddly enough, no mention was made of a half-dog, half-bird creature on ice skates – but there it is in Bosch’s painting, casually going about its business as a weary Anthony is dragged to his feet. “There was already a rich tradition of describing strange creatures and mythical environments in the literature of the day,” says Bickerstaff. “Proverbs, homilies, cautionary tales and biblical allegory fed the medieval imagination. Bosch’s skill was to develop a visual language that illustrated and fleshed out these beings. The bird-like creature delivering a note in The Temptation of St Anthony has a funnel on its head, doglike ears and seems to be wearing skates – who knows what this means? But they are elements that repeat themselves in his paintings. Medievalists and psychologists have spent decades trying to decipher Bosch’s symbols and strange menagerie of creatures with little evidence. They are impossible to figure out, but it’s great fun imagining their purpose or meaning.”

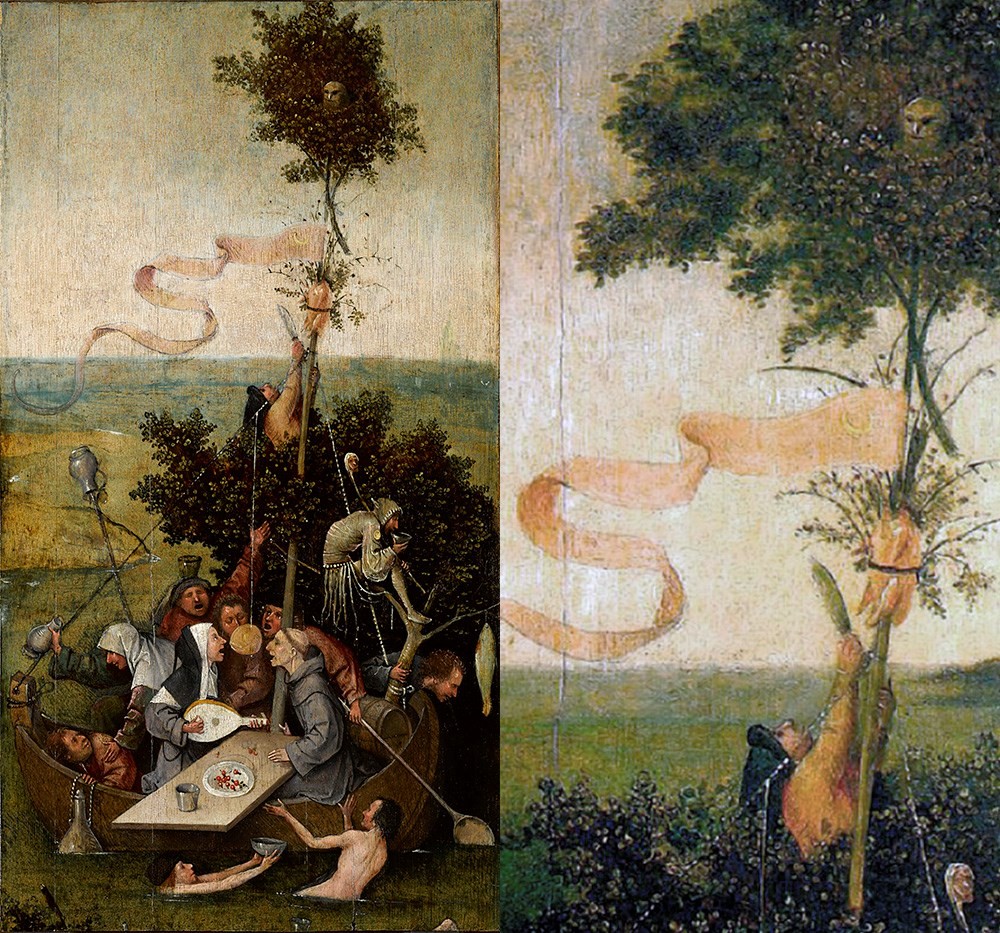

The Ship of Fools

Here, Bosch conjures up a kind of floating Wetherspoons circa 12am, complete with tanked-up revellers clamouring for post-pub nosh. Presiding over the scene with eerie calm is an owl – owls are an ever-present in Bosch’s paintings, though they aren’t, as Twin Peaks’ Log Lady might have put it, what they seem. “[National Gallery curator] Dr Leila Packer says in the film that she believes the owl to be an ominous symbol that is telling us that something is amiss in paradise,” says Bickerstaff. “We in the modern world perceive of the owl as a symbol of wisdom, due to how they are depicted in stories like Winnie the Pooh. But to the medieval world, the owl, with its large eyes and twisting head, was an all-seeing being that sits on high in judgement – a symbol of menace and caution.”

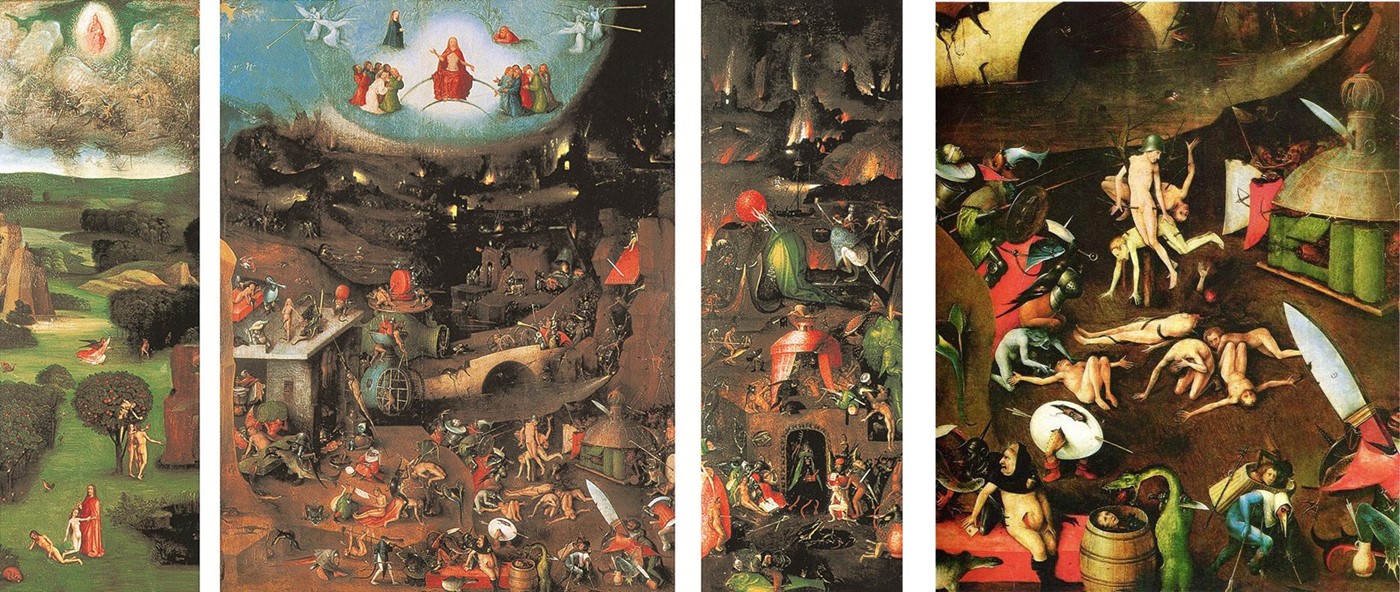

The Last Judgment

Amid the chaos of The Last Judgment’s central panel, an egg with legs stands pierced by a single arrow, one eye peering out through a crack in the shell as if horror-struck by the scene. Like owls, eggs are everywhere in Bosch’s paintings – “a symbol of birth but also entrapment”, according to Bickerstaff – but also, perhaps, a dream symbol plucked from the depths of Bosch’s id. “Sometimes I think Bosch indulges himself in his powers of imagination beyond any direct necessity to illustrate a message or theme,” says Bickerstaff. “There are a lot of scenes within scenes and visual conundrums that serve to confound and entertain in equal measure.” Writing of his masterpiece, The Garden of Earthly Delights, art critic Kelly Grovier notes the tiny egg sitting dead-centre in the scene, in the middle of an X drawn from the painting’s four corners. “Suddenly, the tempestuous vision collapses into a mystical vanishing point,” she writes. “Through the timeless symbol of the unhatched egg, Bosch offers us a way out of his troubled work: the hope of a birth that’s evermore about to be.”

The Garden of Earthly Delights

Was Bosch a stern moralist who saw the world, in the words of art historian Joseph Leo Koerner, as “an enemy territory that should be held in contempt”? Or a sneaky advocate for the pleasures of the flesh? Either way, there’s no mistaking the joy he takes in the details of his fevered canvases. One signature was to take everyday household objects and turn them into instruments of torture: a harp serving as a gallows, a meat grinder used to process human flesh, and, in one fiendish scene from The Garden of Earthly Delights, a bird-like demon on a latrine, chowing down on the damned before excreting them from a giant blue bubble into a cesspit. “[Bosch] plays with our perception of scale and inverts our understanding of the world,” says Bickerstaff. “Everyday devices are scaled up to become industrial machines that consume humans or spew out hybrid creatures. Card tables and backgammon boards also appear frequently, especially in hell, but prosaic objects are usually perverted to evil means. There always seems to be a circle of life being depicted – birth, consumption and death. From heaven to hell and everything in between.”

The Curious World of Hieronymus Bosch is out now on DVD