The Eternal Power of Fear, by Tim Blanks

- TextTim Blanks

From the American nightmares of Raf Simons and Stephen King, Tim Blanks charts the eternal power of fear

Taken from the S/S18 issue of Another Man:

“Woe unto those who spit on the fear generation… the wind will blow it back.” Raf Simons, 2001

The title Raf Simons gave his collection for Spring/Summer 2002 left a contrail of intrigue for so many reasons. The collection itself was pilloried by critics for what they interpreted as terrorist tropes. That point of view only hardened a few months later, on 11th September. But for less doctrinaire types, S/S02 has since picked up a head of steam as “the most important menswear collection of the 2000s”, the moment when Simons’ redefinition of contemporary masculinity hit an inescapable critical mass.

How nice for him. I was more engaged by what Simons meant by “the fear generation”. Generating fear? Or feeling it? The scary or the scared? I loved the designer’s use of the words “woe unto”, with their almost biblical sense of consequence, borne on the wind of retribution.

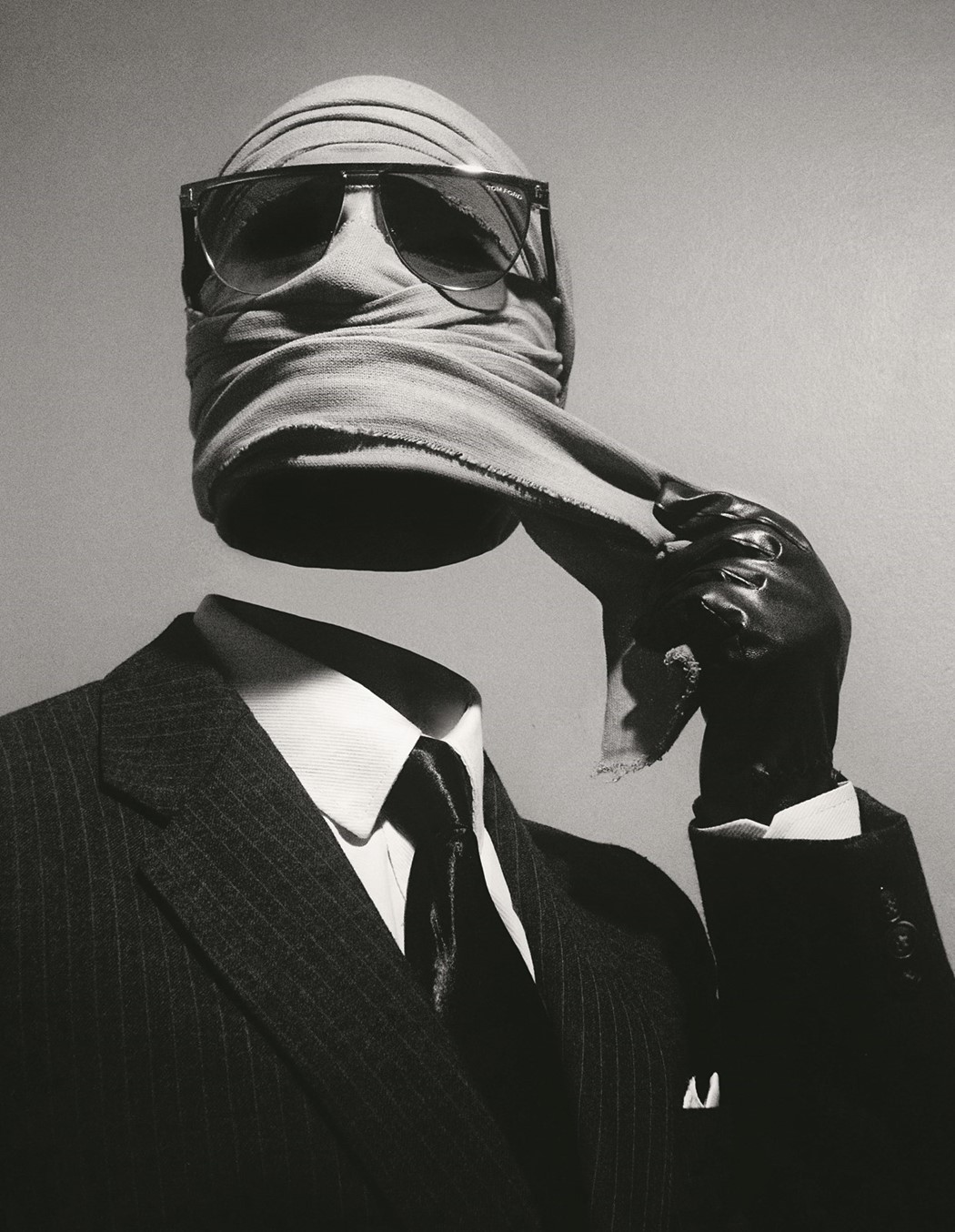

Fast forward 16 surprising years later, with Belgian avant-gardist Raf Simons presenting his second collection for Calvin Klein, the American empire’s go-to label for jeans and underpants, and the fear generation is edging itself to the forefront of fashion, this time on a platform funded by PVH, the multi-billion dollar corporation that owns CK. Imagine my spine, shivering.

When the man himself was still running his business, Calvin Klein was uncanny in his ability to hone in on puritanical America’s repressed horniness. He unleashed the beast. Amazing in hindsight (and in the pages of Rizzoli’s big fat coffee table book celebrating his subversion). But the Puritans didn’t just fear Satan for sex. They were also terrified by the chaos that came after. Indulge me here while I welcome Stephen King, Calvin’s literary equivalent for the way in which he has been able to probe repressed/forbidden recesses of the American psyche to produce work that reshapes popular culture.

How do we count the ways? Carrie! Salem’s Lot! The Shining! The Stand! It! They are universal masterpieces of horror but they are as rooted in quintessential Americana as Klein’s clothing. Especially for outsiders, and that includes not only the college castouts for whom King’s books are sweet revenge, but also those non-Americans who parse his words as a gimlet-eyed record of an idealistic human enterprise gone hideously wrong. (I will use this word once – TRUMP – and insist that there’s never been a better time to re-read King’s masterpiece The Stand.)

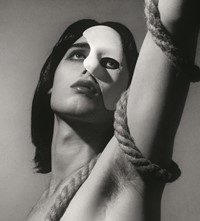

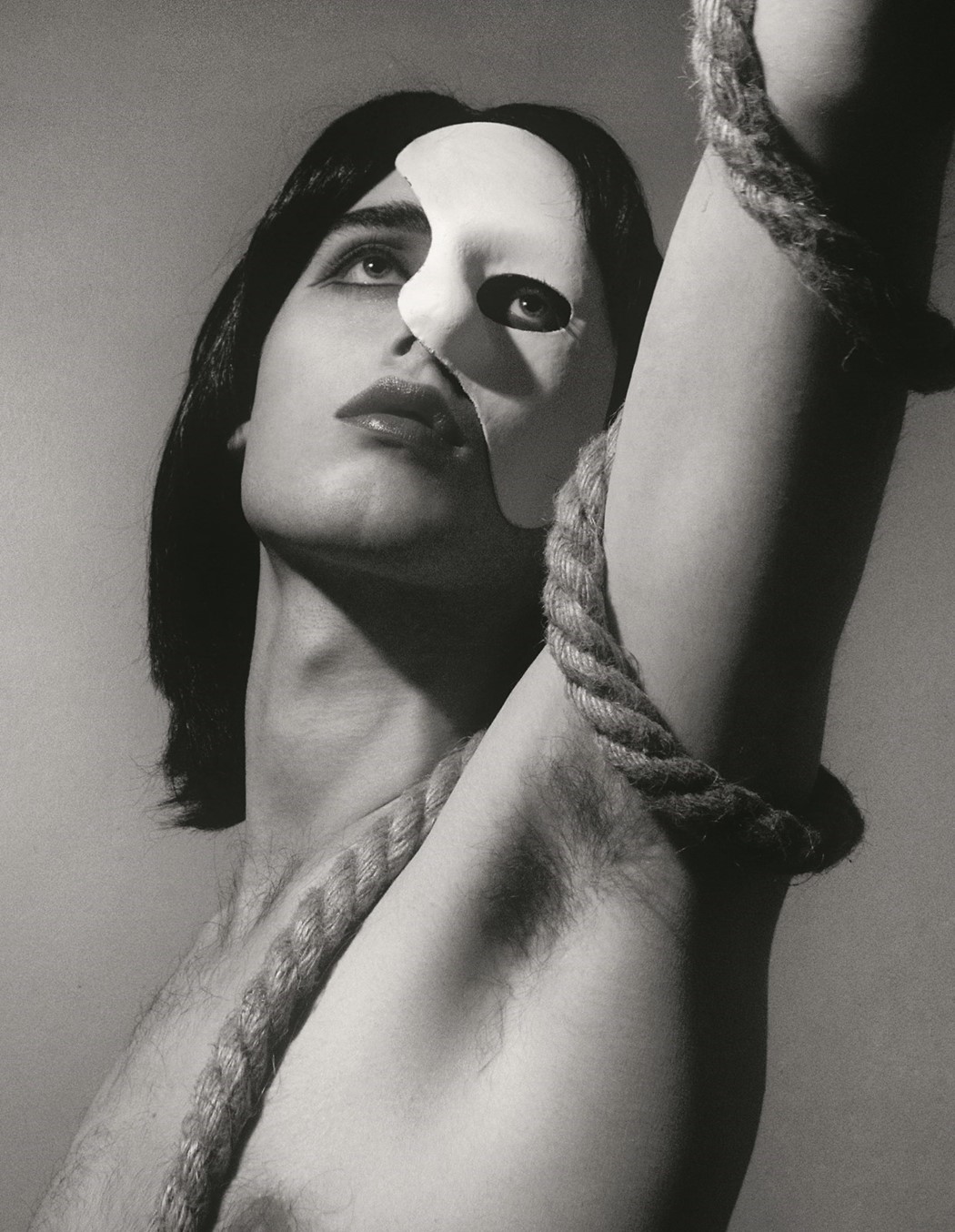

Indulge me again (perpetual indulgence, in fact). One of those non-Americans was Raf Simons. The backdrop of his spring show for Calvin was an orgy of King-isms: the swinging axe of Jack Torrance in The Shining, the pompoms and ominously swaying buckets evoking Carrie’s horrific denouement… and then, within the collection, the blood-stained dresses also summoning up Carrie’s ghastly prom, and the cowboy boots echoing the tchok-tchok of monstrous Randall Flagg’s footwear in The Stand. I’ll concede that there isn’t anything innately evil about a cowboy boot, except that, in the context of a Raf Simons show, all bases are loaded. It wasn’t so long ago that he offered a collection under his own name that stepped through the clean-cut college-boy looking glass into the inverted hell of (David) Lynchland.

“We are in times that are tremendously difficult, sometimes to speak about monsters we need monsters,” Guillermo del Toro sagely observed, while he was winning almost every award available to humankind for his glorious monster movie The Shape of Water. That is where we are now, speaking about monsters. Del Toro’s dream project is a film based on At the Mountains of Madness, a novelette by an early 20th-century American writer named HP Lovecraft. And this is how everything comes together. Stephen King’s interest in writing – in horror, in fact – was sparked by his early exposure to a Lovecraft story called The Lurker at the Threshold (found, appropriately, in his father’s attic). King called Lovecraft “the 20th century’s greatest practitioner of the classic horror tale”. I, in my infinite teen arrogance, assumed that the halls of higher education would accept my interest in Lovecraft as a legitimate subject for a thesis. Oh, how they laughed, just as they laughed at Lovecraft in his truncated, tortured lifetime. Imagine my vindication to discover that anyone from Michel Houellebecq to Mark E Smith was also bowing at his shrine.

Setting aside that momentary bitterness (things worked out quite well minus the university education), Lovecraft said this in 1925: “The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest fear is fear of the unknown.” His acolyte Stephen King amplified the idea decades later: “Fear is fertile and rage is its offspring.” Take a look around. It’s here.

So I’m going to jump to Jack the Ripper. I don’t know what he was (I’m a believer in the transparent membranes that divide multiple universes, which collide on a regular basis, generating massive confusion amongst those with perceptions as defined as ours) but, in one of his arcane missives to the law, Jack wrote this: “Saw you, box of toys”. Those words make my blood run ice-cold. I’ll go out on a limb here and connect with cosmicism, the Lovecraftian notion that ordinary life – box of toys – is a thin shell stretched over a reality so truly alien that it is beyond mere human comprehension. Like Jack, an avatar from another dimension.

Alternate realities are a pop cultural obsession. The Upside Down of Stranger Things is only the most popular of the visions of what lies beyond. Dark offers another. So does The OA. I was partial to Cloverfield and its offspring, until The Cloverfield Paradox with its derivative Alien-isms. But even there, the prospect of a cataclysmic intrusion from elsewhere had an irresistibly resonant thrill. That’s our need for monsters, as Del Toro said.

But particular times breed particular monsters. In the early 70s, during the oil crisis, the cycle of disaster movies in which humanity was consumed by high-rise fire, by earthquake, by giant wave was defined by pundits as a reflection of the helplessness of humankind in the face of fickle fate. Resistance was futile. Then came the solitary stalkers, butchering concupiscent teens, punishing America for losing touch with its Puritan roots.

What monster has contemporary culture conjured into being? Our current flirtation with apocalypse looks like it’s driven by climate change, more so now that we know the space beasts in the Cloverfield trifecta were released by an effort to remedy environmental catastrophe. “Two distinct realities interacting in a multiverse chaos,” says the scientist by way of explaining the “paradox” run out of control.

“Out of control” is the key. No one had a clue what monsters the internet would unleash. Utopian dreams of an enlightened global connective evaporated in horrendous trollery and cat pix. That’s “human” nature for you. But it also seems to be very much about our uncertain relationship with technology, and the way it is exposing us to the unpredictable unknown. The more we discover, the less we know. Information doesn’t equate with enlightenment, even less wisdom. The first line of Lovecraft’s 1926 story The Call of Cthulhu refers to “the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents”. For him, that unknown sparked paroxysms of dread. He externalised it in a fabulously alien cosmology that knocked L Ron Hubbard’s Scientology crap into a cocked hat.

Lovecraft proposed the Earth as the site of a last stand between gigantic entities (religion would dub them God and the Devil) with the losers exiled to the Pleiades. With a little chemical assistance, I would lie in the backyard gazing up at that particular, easily locatable constellation and will the colours out of space that Lovecraft wrote of. Confronted by nothingness, many of us want to feel something, anything. And that, more often than not, is fear. Logical enough. Quite grand in a way. Who hasn’t wished in a desperate moment that the veil of their everyday could be torn asunder by an overwhelming visitation from HR Giger’s alien? How would we react in a moment of consummate horror? Edmund Burke, the 18th-century Irish philosopher who is regarded as one of the fathers of conservatism, wrote, “The strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling inclines us most to the sublime.” For him, that emotion was terror. (The only person I know who regularly uses the word “sublime” is Raf Simons. Just saying.) I can’t think of anything more likely to induce existential fear in an organism as narcissistic as man than a sense of his cosmic insignificance. Maybe the only thing we have to fear isn’t actually fear itself. Stephen King says, “The most awful word in the English tongue is ‘alone’.” The chaos of the cosmos implies isolation on a maddening scale. Is that where the sublime hides? Not being a self-destructive romantic poet, I hardly feel qualified to judge.

Still, in confronting the swirling, psychedelic, unsettling void of the Great Unknown, I’m willing to heed proto-psychonaut Arthur C Clarke, whose Third Law of Prediction is this: Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic. (The other two laws are almost as good.) I’m still wondering about the fear generation. I don’t think Clarke’s words are necessarily a salve for unmoored psyches, because magic is a challenge that demands levels of comprehension and cohesion that human beings seem less and less possessed of. I found these words somewhere else, wish I could remember where: “Modernity suddenly feels less like a barrier to supernatural threat and more like a highway for its transit.” They seem more like words for the fear generation to live by.