Being Stanley Kubrick’s Right-Hand Man

- TextHynam Kendall

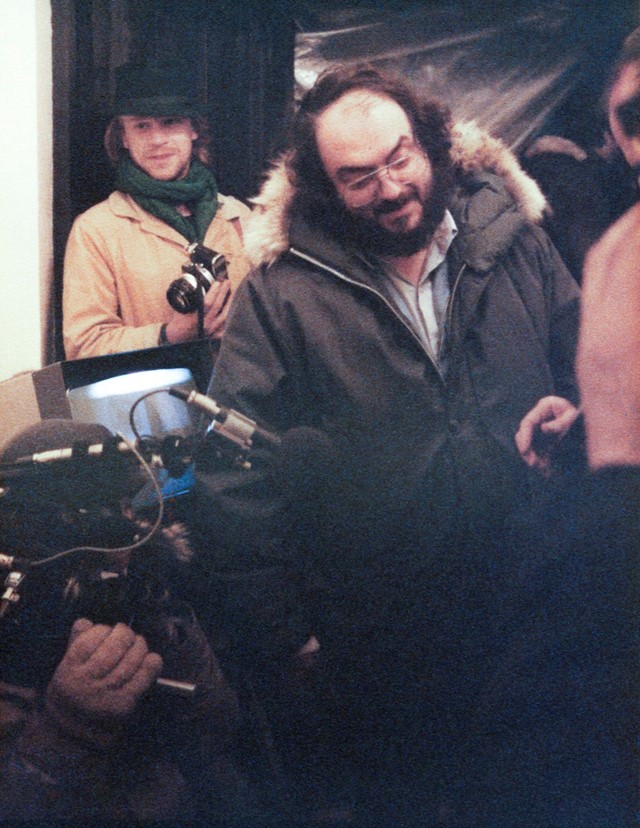

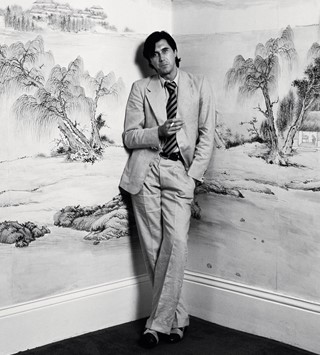

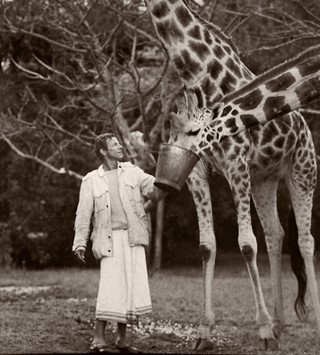

In 1975, Leon Vitali surrendered his promising acting career to serve ‘a genius, who was at the service of art’: Stanley Kubrick. As a new film about the legendary director hits UK theatres, Vitali tells his story...

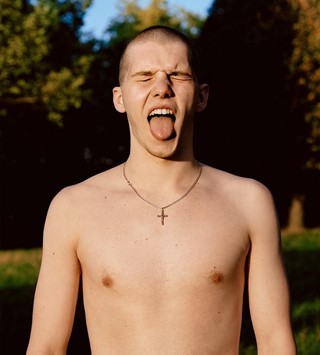

In 1971, Stanley Kubrick’s dystopian juvenile delinquency epic, A Clockwork Orange, hit cinemas in a whirlwind of controversy and intrigue. In a London theatre one groggy evening, a young Mick Jagger-looking audience member watched aghast, turned to his friend at the end and said, “I must work for that director!”

Under normal circumstances, this statement would sound completely absurd. However, the young man in question was rising star and burgeoning pin-up Leon Vitali, an actor gaining traction for a myriad of roles in BBC dramas, the theatre and the odd sitcom, some of which even gave him second or third billing.

After relaying this ambition to his agent, Vitali the unthinkable happened: he was given the chance to actually audition for Stanley Kubrick, eventually securing the juicy supporting role in the director’s 1975 Oscar winner Barry Lyndon.

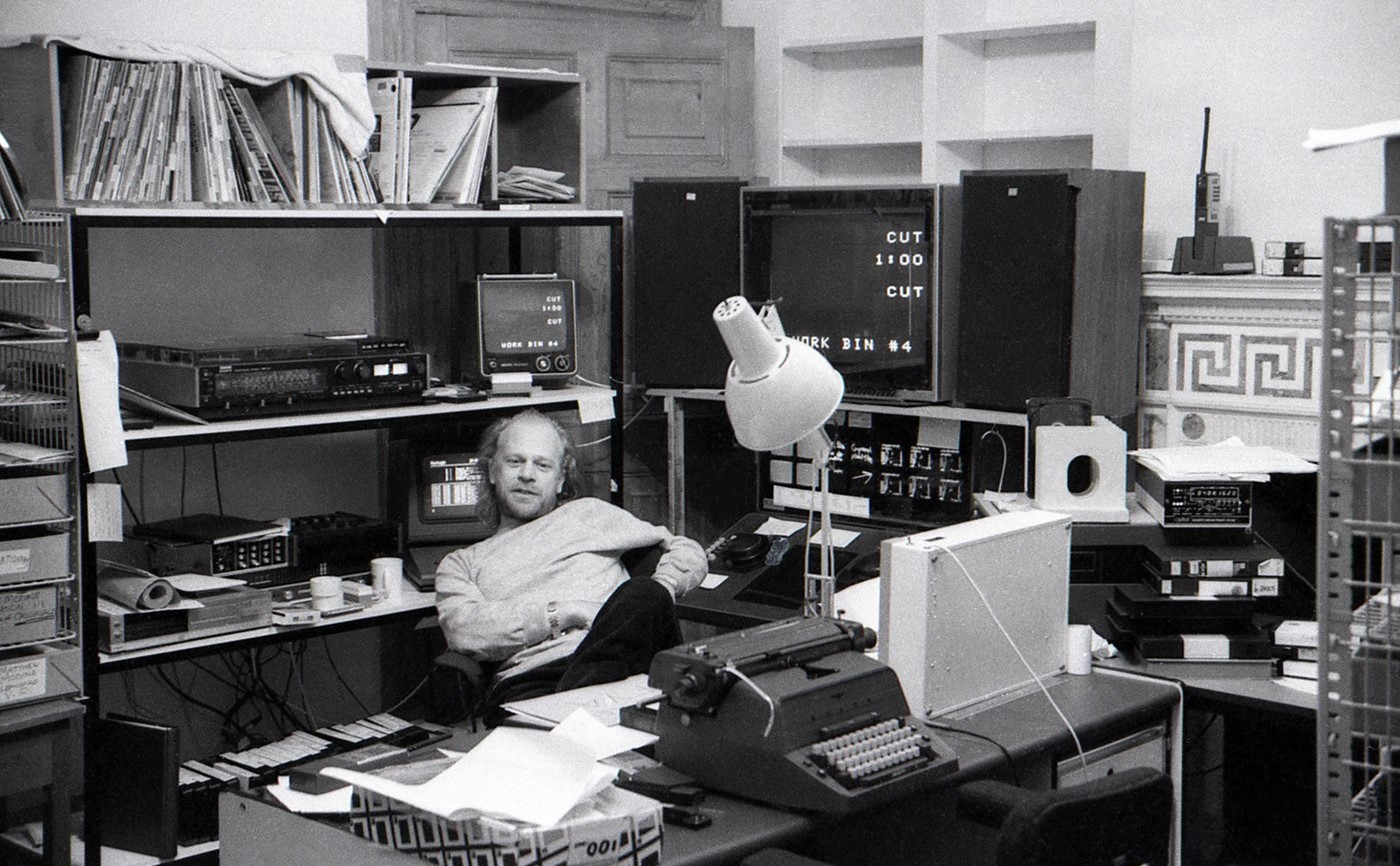

Between takes on set, Vitali would barrage Kubrick with questions: how did the equipment work? Why would he operate the equipment this way or that? Vitali’s interest and passion abounded, with him finally asking Kubrick if there would ever be a possibility to work for him. Kubrick, testing the sincerity of the offer, set Vitaliti to task, and his assignment was thus: to go to the US and cast the child role of Danny Torrance in Kubrick’s upcoming film, The Shining.

Vitali tested countless child actors, finding, casting and even coaching the eventual – and lauded – choice, Danny Lloyd. Impressed by his commitment, Kubrick would go on to employ Vitali as his “right arm” for over two decades, having Vitali do every job from research, assisting, casting, production inventories and even acting as Master of Ceremonies “Red Cloak” in one particular film, Eyes Wide Shut.

In Tony Zierra’s documentary Filmworker, out tomorrow, Vitali recounts a life with one of the world’s most celebrated auteurs. In anticipation of its release, and alongside an exclusive clip, Vitali talks to Another Man.

AM: Filmworker opens with the metaphor of a moth being attracted to a flame that would burn it. Is this a fair description of your relationship with Kubrick?

LV: With Stanley, it was a feeling in my gut that I had to work with him, it wasn’t anything more calculated or masochistic than that. Through luck of an audition, there was a kind of direct access to this dream – an entry, a way in. This is perhaps why I feel it was more of a kind of serendipity than anything else. Meeting Stanley was the first time I thought I might be anything other than an actor. If I hadn’t have met Stanley, I would have stayed an actor, absolutely.

“I never thought I was giving any part of myself up because I was so in love with his whole world. I was lucky. I was part of a creative process that made art that was bigger than me”

AM: In the film there is a sense of your career change being for ‘the greater good’. At times your colleagues describe the decision as ‘selfless’.

LV: Yes that’s a genuine feeling that I had, and still have it – that it was for the greater good. I never thought I was giving any part of myself up because I was so in love with his whole world. I was lucky. I was part of a creative process that made art that was bigger than me.

AM: Initially you had concerns about Filmworker, as you didn’t want it to come across as ‘glorifying’ yourself

LV: It sounds so counterintuitive, but even from my acting days, I didn’t want personal attention beyond the acting. You could even say I have sympathy for the big movie star types. For example, Nicole Kidman, who is an incredible actor that I am lucky to have worked with [for Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut], was at Cannes last year at the same time as me. I was there with Filmworker, and she had four movies there herself and had to spend all day every day being interviewed. There was no time to see each other. Time is not her own. It’s not when you’re a huge star. So I have always been wary of that. [With Filmworker], I agreed also because I wanted people to know what work goes on ‘below the line’ and was anxious to highlight those people, of which I’m one. I always sit and watch a film through the credits to completion in tribute to them. I wait all the way until I see those important words: The End.

“He died in March [1999] and there was so much work to do on Eyes Wide Shut that I didn’t stop to let myself experience it until I finished the last print of the film in October. And then I felt it. He wasn’t around. And I was alone”

AM: Was the process hard or uncomfortable for you at all?

LV: Yes. Absolutely. It even became like a huge giant public therapy session in a way. Tony [Zierra, the director] would be the first to admit that it took some time for me to come into it. After a few sessions, he decided we should go up into my attic to look through my stacks of notebooks. Stanley always told me to write everything down, and so I did. There were hundreds of notebooks up there, believe me. Being around them started to relax me. I had existed in Stanley’s world for so long, so it was a strange feeling to detach myself from years and years and years of subjectivity. And then, there, surrounded by these notes and memories, it started to come back to me. You know, he died in March [1999] and there was so much work to do on Eyes Wide Shut that I didn’t stop to let myself experience it until I finished the last print of the film in October. And then I felt it. He wasn’t around. And I was alone.

AM: You were working sometimes literally 24 hours a day, co-habiting with him. Your role in his life has been described as his ‘right arm’. When you are devoted to someone like that, is there the feeling of some kind of loss of self?

LV: No, because luckily I have a strong sense of self-identity – not to sound quasi-Freudian here. But I’ll tell you, it was the first time I ever felt bereft. And the first time I ever went onto antidepressants. Understand it wasn’t just the work with Stanley, I lost a friend. If you upset him he gave you a rocket, sure, but he’d often also say, ‘let’s sit down for a minute,’ and in those moments we would talk about so much – politics, soccer, actors and movies we liked. And every time we did that, it was back to when we first met.

“For me Stanley was the most transparent human being... If he was angry, he was really angry, and if he was kind, it was sometimes too much to take”

AM: There are Kafka-esque tales of you and the crew sleeping fully dressed amidst piles of endless work that refused to go down. Due to this and Kubrik’s lack of press relations, there was a myth about him, he had reputation for being somewhat dictatorial. But the man you describe in Filmworker, sounds very different.

LV: Oh yes, for me Stanley was the most transparent human being. If he felt something, you saw it absolute. If he was angry, he was really angry, and if he was kind, it was sometimes too much to take. And the way he worked was unbelievably collaborative, which people didn’t know. He was often called a control freak but actually he allowed all the actors to do a scene however they wanted to. Some actors say, “well he never directed me” and that’s not true. What he did was to make you go over and over the scene in order that you find your way into it. It was a gentler way. It was always still his vision.

He knew that the medium is one of the most collaborative there is and allowed everyone to enter the dialogue and as a result the project would change and develop as we were making it. We started off with a script, and by the end of the shooting you often felt, “oh! How did that get to this? Where did that original movie go?” He was strong enough to allow the film to go somewhere else if and when it needed. And let me tell you, he just didn’t care about what people said about him, how they perceived him. For him, he had one focus, which was the movie, the art.

AM: There are only a few directors whose name has entered the lexicon. Kubrick’s is one, and we hear of things described as ‘Kubrickian’. What does that term mean to you?

LV: I think his name has entered the lexicon because he’s widely accepted as a genius. In the film he is referred to as ‘master’ and his work as ‘glorious’. Genius is a fight against convention. Artists are disobedient. They cannot help but break the rules. If anything describes Stanley, I suppose that does. Because you can’t put your finger on the work, there’s not one way to explain it. No two of his films are the same. For example, Full Metal Jacket and Paths of Glory are both war movies, but exist completely separately from each other. He played with every genre and the nuances within those genres. The great people are those whose work you can revisit over and over again because the architecture of what they do is so ingenious and striking.

“Genius is a fight against convention. Artists are disobedient. They cannot help but break the rules. If anything describes Stanley, I suppose that does”

AM: In the film, you saw that sometimes there was a cost to your devotion. Your children quite candidly discussed the periods in which you were unavailable to them when they were growing up. But there was never a sense of regret from you?

LV: No. Never. And there still isn’t, believe me. I was working with someone of great, great, great talent. The pleasure of that is like an ointment for any bad moment I might have had. Coming to Stanley with my work to look over was the most terrifying part, wondering if he was going to like it. But it wasn’t a fear of Stanley. It was a fear of whether I did it well enough, knowing what the end piece would be. Knowing that it would be art. The pleasure of the art validated everything.

Filmworker hits UK theatres today