Artist Allen Jones: ‘You Have to See Copying as a Compliment’

- TextBen Cobb

From Steven Klein to Stanley Kubrick – filmmakers and fashion photographers alike have ripped off the work of Allen Jones. Here, speaking to Ben Cobb, the provocative artist shares his feelings on plagiarism and today’s ‘name and shame’ culture

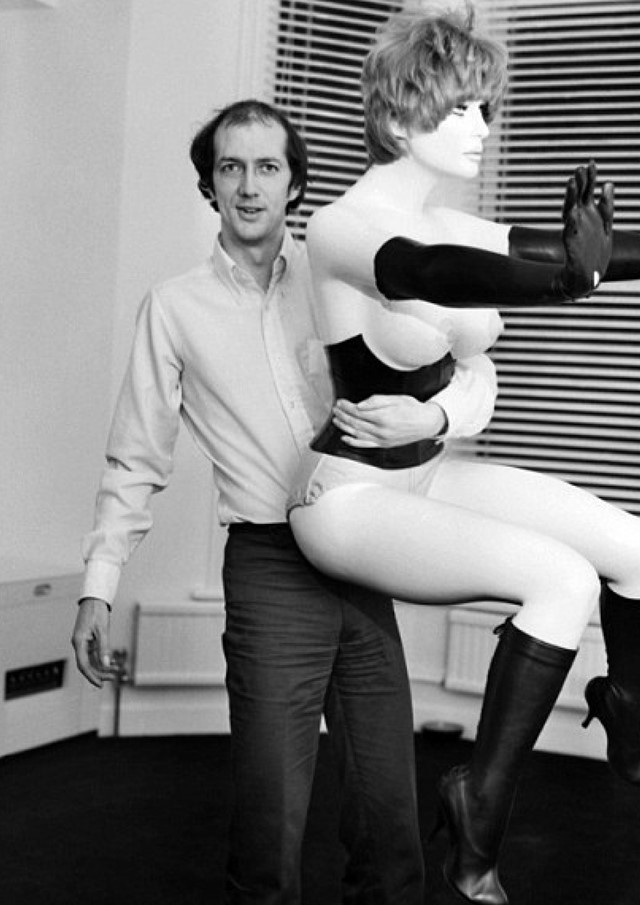

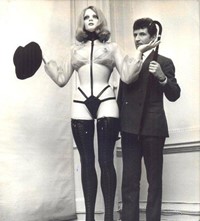

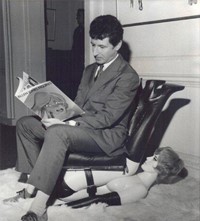

If you don’t know the name Allen Jones, you will most definitely recognise his furniture sculptures. Models of pneumatic women dressed in killer-heeled fetish uniforms, posed as a hatstand, table and chair, these erotically-charged ready-to-serve objects are unforgettable works that have entered the public consciousness – and, from their unveiling in 1970, whipped up ferocious feminist debate. Along the way, they have also been heavily referenced, reappropriated and just plain ripped off in fashion shoots, art pieces and advertisements. Not that Jones seems to mind: over the years, he’s kept a drawer full of images of these copycat incarnations. He’s even turned them into a new book, Allen Jones Copied – From A Higher Priced Original, published by IDEA.

Sat at a small table in his warehouse studio, cup of tea in hand, the 80-year-old pop artist flicks through the pages of Copied. It’s the start of an ongoing series: next up a book of “close-up photos of the anatomy of my sculptures, they’re quite sexy”, he explains, followed by a collection of Jones’s obsessive photos of road markings (cue an inspired mini-lecture on the Baroque Period of parking lines). Laid out on a nearby desk are print-outs from a forthcoming film project that, in the grand tradition of the Pygmalion myth, brings his famous Hatstand sculpture to digital life; the original stares blankly at us from the other side of the room, hands still patiently held out, frozen on a white fur rug for almost half a century – next to her, the gold body armour suit made famous by Kate Moss.

Returning to the book in front of him, Jones stops on an image of a dull domestic scene: two women chatting on a sofa, drinking red wine; in front of them, a man on all fours with a glass table surface on his back. The tagline reads: “Curry that helps you get the most out of your husband.” It’s an advert for Quorn tikka masala. Jones smiles to himself, still incredulous and moves on to the next page…

Ben Cobb: Where did all the material in Copied come from?

Allen Jones: Half the stuff comes to me unsolicited; people find my address and send it to me. Others are from people who have created something and think I might like it because it’s an affectionate take or a parody. A couple of times a year I’ll get images from an art dealer because someone has brought in a piece, like an upturned figure, and they’ll ask, ‘Is this yours?’ – some art dealers really should do better research. Most recently, there have been advertisements on the London Underground and high-end glossy magazines do parodies which are actually terrific photos and look quite sexy.

BC: In particular the Steven Klein shoot from Interview…

AJ: With that one shoot, what’s interesting isn’t that it was influenced by my work in general, but that it’s based on such a specific newspaper image of me. I quite like that… but it would have been nice if there had been a small credit in the magazine somewhere. Usually they’ll tell you what shoes the person is wearing and since the whole thing was plainly a rip-off of my images, I just thought that showed a lack of style to be honest. Whereas Skin Two, the fetish magazine, has often used my work for ideas, but they usually put a little gesture or acknowledgement to me in there.

BC: Rather than outrage, do you feel flattered by these imitations?

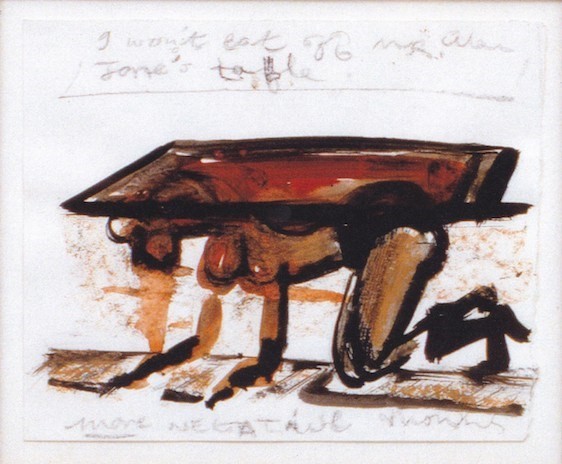

AJ: There are three things in the book that are by female artists and all of them plainly make their own statement on the back of my sculptures: that’s fine, that’s legitimate. I was quite tickled to see Marlene Dumas had based one of her drawings on my table sculpture and includes a little acknowledgement. It’s nice to see that your work has entered the fabric of art in that way, that it’s used as a sounding board, something to bounce ideas off. I also included a Chinese parody in the book: the artist’s original work is about 30-feet long and features all these famous tableaus from the history of art so, of course, it’s a bit of a kick that someone on the other side of the world should include it.

BC: That is very much within the art realm, and there’s a strong tradition of artists referencing other artists throughout history. But when your work is borrowed as part of advertising and there’s a commercial element involved, do you feel differently? For instance, the Stoli vodka advert in the book…

AJ: Well, with that there is a possibility that they chose to use a man as a table sculpture instead of a woman to play that feminist/chauvinist game. But it could also be that by changing the image they knew that then I couldn’t make a case out of it because, so I am told, you cannot patent an idea. You can patent a thing or an object, but not an idea. I think Jeff Koons was taken to court as he did a sculpture of some people sitting on a park bench that he copied from a photograph. The photographer recognised it and took it to court but he didn’t win because the simple truth is that his work was a photograph and Koons’s was a sculpture. However, I’ve never tested the idea in court because I’ve never sued anyone.

BC: Have you ever been tempted to?

AJ: No. Most recently, there was that image of Dasha Zhukova sat on a black version of my chair sculpture. It was Norman Rosenthal who first told me about this Scandinavian artist living in NY who was doing versions of my furniture sculptures but turning the women into black women. Then I saw one in the paper with Dasha sat on it and there was this whole controversy… My take on it was that either an artist adds something to the argument or the original story in which case it’s something you take notice of, or it doesn’t. To me, it didn’t get my juices going the fact he’d made a statement by simply making the figure black. Also, it looks as though they were body casts and that’s very different from sublimating the thing into some idealised figure, which is what I do. In the end, I wasn’t outraged by it; it just would have been nice if it had been something that I thought was pretty good.

BC: What do you think makes a good rip-off?

AJ: I think if it has some humour to it or brings something else to the table, or you can see that someone has done an elegant take on it, then you realise there is some artifice to it. To be honest, I’ve never really analysed my reaction to all these imitations. But I was obviously interested in these things enough to keep them. The spectrum was so broad that it seemed to me to be an interesting idea to externalise it in a book and make a statement out of it…

BC: And what statement are you making?

AJ: It’s a statement about the power of an image. The image of those sculptures I’m sure have been used many times by people who have no idea of my name or what I do. They just might have seen it in a book and thought, ‘That’s a great image!’ And to be plugged into the popular consciousness in that way is… satisfying is the wrong word, it sounds too lofty, but it feels nice to know I must be doing something right. I’m interested in that popular consciousness rather than the ivory tower of the Art World.

BC: I like the idea that if you put something on your table sculpture or sit on one of your chairs, it immediately stops being art and becomes design…

AJ: Yes, exactly and that actually happened at the gallery opening. Everyone was stood around in the crowded room with a glass of wine, and this woman had finished her glass and she was just about to put it on the table sculpture and she suddenly caught my eye and mouthed, ‘Is it alright?’ I shrugged, meaning that was her call: for me, that was a confrontation, a decision she was having to make. ‘Is this an artwork?’ So, in that way, I thought it was a successful sculpture because it threw up all those funny questions.

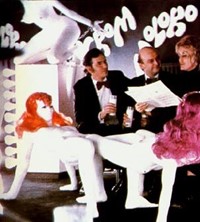

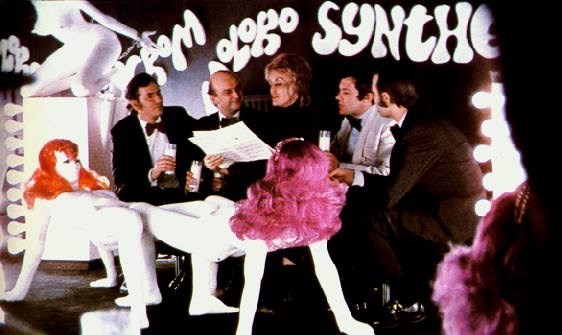

BC: In the book, you include a still of the Korova Milk Bar from Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange… Was that one of your earliest experiences of being copied?

AJ: I never met Kubrick, we only spoke on the phone – he was famous for that. He sent me the Anthony Burgess book and at first his questions was, ‘Would I work on the film?’ I thought I could do it and did some drawings for the furniture; I wasn’t thinking about the table sculpture, I was trying to do something new for him. When it came down to it I said, ‘If I do this, it’s going to be about three months’ work’ – I was teaching part time back then and I couldn’t afford to work for three months for nothing!

BC: Let me stop you there: Kubrick wasn’t going to pay you?

AJ: No, he thought I would do it just for a credit. Kubrick’s words were: ‘I’m a famous director and you’ll get a lot of work off the back of this.’ I couldn’t quite believe what I was hearing. In probably my finest moment, I replied to him: ‘Yes, but I’m not a set designer. If you get me a show at the Louvre then I’ll do it.’ In the end, I realised it wasn’t going anywhere so I said, ‘Listen, you like the idea, feel free’.

BC: So you just gave him your idea?

AJ: Yes, but I’ve always seen fine art as a laboratory for visual ideas. My design for the waitress uniforms at the Korova with the backside cut out – the costume is in the book too – ended up becoming my Waitress project, so everything gets used.

BC: You’ve mentioned before how you got the idea of a figure as furniture from an image you saw in a fetish magazine… Is that maybe why you feel so easy about other people copying your sculptures? Because you took the original idea from somewhere else…

AJ: Yes, quite possibly – that’s an interesting point. The source was a popular non-fine art publication and then the image has fed back into the popular domain.

I’m sure that this is the same for all artists but your only responsibility when you’re making the work is to the canons of taste. You just make it as honestly and directly as you can but once it’s on the wall, it’s open season. The cliché is to say it’s like your child: you have some control over a child’s environment and how they see the world but once they leave home and they’re out there in the world, you’re not responsible for them or their actions or how people respond to them… Actually, maybe that’s not such a silly analogy.

BC: There is also something very timely about this book. On Instagram, there is a rabid culture for naming and shaming plagiarism, calling out references… Do you think that’s a positive development?

AJ: I’m an old man so I don’t look at Instagram but that’s interesting, I didn’t know that. The truth is it’s a tough world – there’s another cliché for you! You know Nobel Prize winners get the prize but there are probably 20 people behind them working away, sharing their ideas with the prizewinner. It’s an eternal debate.

BC: What advice would you give to a young artist who has seen their work ripped off?

AJ: They have to see it as a compliment and see it as advertising… otherwise you’ll just go crazy. So I say, take it as a compliment and move on.

Allen Jones Copied – From A Higher Priced Original, published by IDEA, is out now.