The curator of the Photographers’ Gallery’s new exhibition about cross-dressing unpacks the lesser-known history of this practice

- TextFrancesca Gavin

Obsessions can start young. French filmmaker Sébastien Lifshitz, who is best known for Bambi (2013), a documentary about France’s most celebrated transsexual, was always drawn to trans history. He had been collecting photographs of cross-dressers from flea markets, junk shops, eBay and the like since he was ten. After directing Wild Side (2004), a feature film about the life of a transsexual woman living in France, he became even more inspired by these ‘bruised existences lived against the grain’ and began to collect, often anonymous, photographs more seriously. Some of these images were published in two books The Invisibles: Vintage Portraits of Love and Pride Gay Couples in the Early Twentieth Century (2014), while many are going on display at a new exhibition at the Photographers’ Gallery, opening on Friday.

Ahead of the opening, curator Karen McQuaid discusses the exhibition and why photography sheds light on a lesser known past.

When was cross-dressing first documented?

As a social practice, it has a scattered but pretty continuous history that reaches as far back as gender-specific clothing itself. There are literary and figurative representations of cross-dressing from the Aztecs, the ancient Egyptians, Greeks and Romans. It shows up in Norse mythology, the Hindu epics and the Odyssey. It was prohibited in the Bible in Deuteronomy 22:5 and it was effectively made illegal in the UK in 1885. So it’s safe to say it’s been around a while…

When were images of cross-dressers first exhibited?

We have photographs in the exhibition dating back to the 1880s. Interestingly, while we were planning our exhibition, the National Portrait Gallery acquired a portrait of celebrated diplomat and cross-dresser Chevalier d’Eon by Gilbert Stuart. It’s the first painted portrait of a man in women’s clothing in their collection. We know that the Stuart portrait is a copy of an earlier painting by Laurent Mosnier – and that was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1791.

What is the relationship between photography and the history of cross-dressing?

Photography is key in providing evidence of people resisting the dominant and prescribed way of ‘being’ – some do so boldly in public and some quietly behind closed doors. These particular photographs prove varied and long-standing precedents for today’s diverse trans and queer spectrum. For many cross-dressers, and people playing dress-up in order to explore their identity, photography offers reassurance, some sort of visual arbiter that they have succeeded in achieving the look they aimed for. A lot of people only wish to present as someone from the ‘opposite’ gender, or indeed as someone non-binary, for part of the time, and sadly many people do not feel safe enough to be as they wish to be in public. A photograph can stay with you, in your hand, you wallet, on your phone or on your person – with you at all times, when you’re in ‘drab’ or your everyday clothing as a reminder of another, perhaps truer version of yourself. Photography has always been used as a site for reinvention and self-expression.

Who were people in these images?

The anonymous nature of the majority of these photographs means you can do little but speculate about the lives of the people posed in them or took them. The people in these photographs would have had very different motivations for presenting as they do before the camera. The degree of acceptance from their chosen community and wider society would have varied greatly – as would the levels of personal risk involved. As you wind through the show you encounter a range of scenarios, environments, you jump across decades and through both private and public space. The tension between public and private space, and public and private self, is felt throughout the show.

Is there any relationship between performance and these characters?

Some of the most fascinating photographs in the exhibition are from theatres that were set up within Prisoner of War Camps. POW’s set up makeshift theatres to occupy themselves and men took on female roles. Often these ‘drag-soldiers’ would continue cross-dressing offstage, becoming camp ‘stars’ and gathering fans. This phenomena is a really good example of suppressed narratives, as their very existence was long brushed under the carpet. Today, historians recognise that female impersonators were an integral part of camp life.

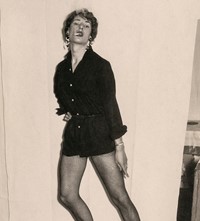

Cabaret and performance is present in many ways in the exhibition – from Bambi’s backstage photographs from Le Carrousel de Paris in the 1950s to American drag institutions such as Finocchio’s Club in San Francisco and the Jewel Box in Miami, both opening in the late 1930s and 40s. Some of the photographs of entertainers and performers would have been shot at professional studios with a team of skilled artists and technicians. Tools for promotion, these ‘headshots’ would have ended up cabaret posters and in the press. But there are many examples too of people turning the wall of their front room, or a sun-drenched garden porch into their own studio, and approaching it with every bit as much seriousness and theatrical poise.

Under Cover: A Secret History Of Cross-Dressers is at the Photographers’ Gallery, February 23–June 3, 2018.