Before and after the 1979 revolution, rock and roll musicians looked towards Iran – something that is often ignored, writes Joobin Bekhrad

- TextJoobin Bekhrad

Given the slew of vitriol that has often surrounded Iran in the mainstream Western media since the 1979 Revolution, it’s not a country you tend to associate with … rock and roll. Yet, both before and after Ayatollah Khomeini returned from exile in France to found the nascent Islamic Republic, rock and roll musicians of the 20th century looked towards the land of roses and nightingales for inspiration; in fact, one of the greatest was even Iranian himself. When it comes to Eastern environs and rock and roll, however, minds usually turn towards the usual suspects: the Stones in Tangier, the Beatles in Rishikesh, Page and Plant wandering around the Sahara Desert, and all that. Many Iranian ‘chapters’ of rock and roll history have been largely forgotten, overlooked and relegated to the gossamer-strewn recesses of memory, which is a shame, especially considering how great some of them are.

The ‘story’, more or less, begins in 1968. That is, of course, overlooking Iran’s sartorial influence in rock and roll via paisley – or the ‘Persian pickle’ – caftans, and other fashion staples rooted in ancient Iranian culture. On his way back from India, Paul McCartney and girlfriend Jane Asher decided to stop over in Tehran, where they feasted on sumptuous stews, smoked ghalyans (the original water-pipe), and jammed with the late, great Vigen, one of Persian pop’s leading figures, who strummed his guitar just for Macca. The same year saw the filming of Performance (released in 1970), Nicolas Roeg’s surreal, catatonic thriller starring Mick Jagger and James Fox. At the heart of the film is Iran – or, Puuushia, as Jagger and co. prefer to call it. Behind Qajar-era mirrors, Jagger recites Iranian legends. He also, much to Keith Richards’ dismay, makes love to Anita Pallenberg to the sound of classical Iranian santoor music, and amidst a hodgepodge of Iranian rugs and textiles. To add to the Iranian theme, the nymph-like groupies surrounding him in his stately London pad tell him they’d much rather become ‘bandits in Persia’ than go to America, and the final scene sees Fox hitting the high road after leaving a note that reads ‘Gone to Persia’.

Some years later, in 1970, Eric Clapton decided to woo best mate George Harrison’s wife Pattie away from him. The best way to do it? By way of a medieval Persian romance. The inspiration for Layla, the guitar slinger’s most well-known tune came from Layla and Majnun, penned by the 12th-century Persian poet Nezami Ganjavi. Used as a Sufi allegory by Ganjavi, Clapton was gifted a copy of the book by a friend who was converting to Islam. With the addition of Clapton’s throat-rending pleas and Duane Allman’s silky-smooth slide guitar lines, it became one of the former’s defining moments. Clapton wasn’t the only one to look towards Iran’s poets for inspiration however. According to Mouse and Kelley, the artists behind the Grateful Dead’s iconic Skull Fuck album and accompanying concert posters, the ‘skulls and roses’ imagery was taken from an illustration in an edition of the Robaiyat (Quatrains) of the 11th-century Persian poet and polymath Omar Khayyam. The transience of life and inevitability of death were – in addition to hardcore wine-imbibing – subjects that many of Khayyam’s poems revolved around, making the Dead’s imagery at once aesthetically fitting, as well as meaningful.

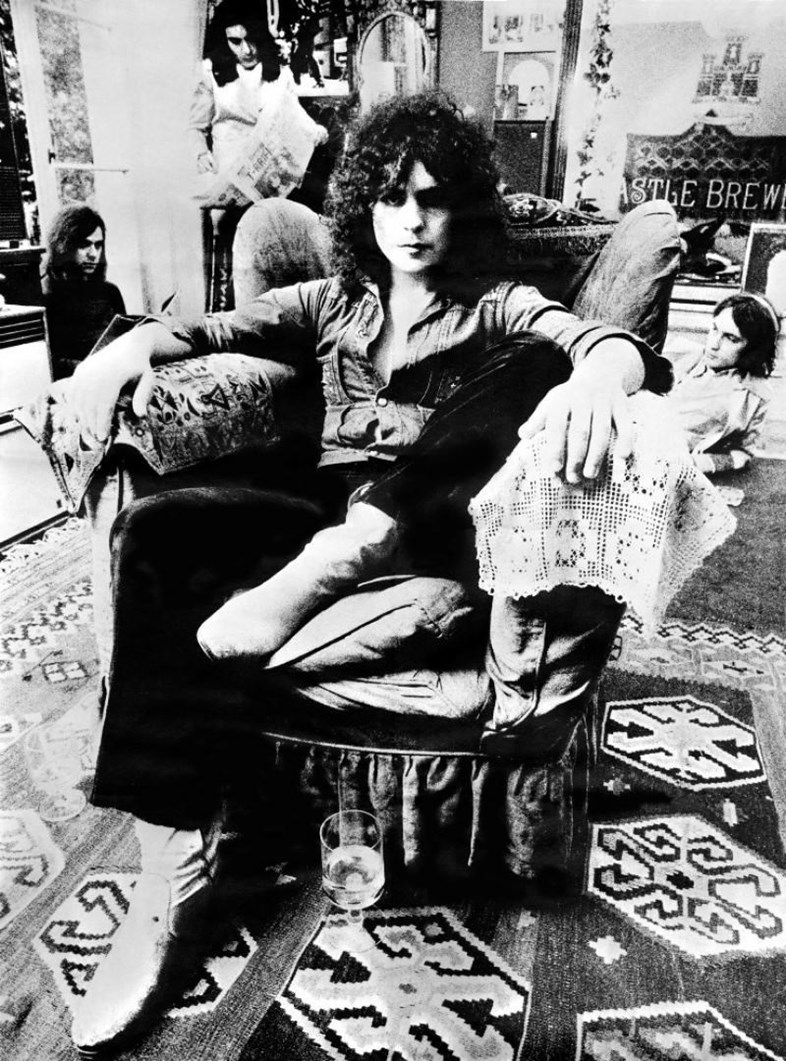

It goes without saying that where there is mystery, romance, and ‘exotic’ environs, there’s Marc Bolan, the daddy of glam rock snuffed out too soon. If there’s anyone who takes the cake for the most references to Iran in rock and roll, it’s Bolan. I’m a labourer of love in my Persian gloves, he famously sang on Hot Love (1971), one of his biggest hits. The name-dropping continued afterwards as well: Do the monkey wrench on a Persian bench, he instructed on Explosive Mouth (1974), while on City Port (1977) he looked up to the sky: Peering eyes and Persian skies removed my eyes and took them right away.

Speaking of eyes and looking up to the sky, no account of Iranian episodes in rock and roll history would be complete without mention of the larger-than-life Freddie Mercury. Before he was ‘Freddie’, the rock god was Farrokh Bulsara, a goofy-looking Parsi (Persian Zoroastrian) boy in Tanzania. Freddie and his family, like all other Parsis (the term literally means ‘Persian’), were adherents of Zoroastrianism, the ancient monotheistic Iranian faith, whose ancestors had migrated to India from Iran in successive waves, beginning in the eighth century. “I’ll always walk around like a Persian popinjay,” he once remarked in an interview, “and no one’s gonna stop me, honey!” More recently, in a BBC documentary about Zoroastrianism and the Iranian New Year, Freddie’s sister Kashmira mentioned how proud the singer had been of his Iranian ancestry and how his ancient Iranian faith had inspired him throughout his short, yet brilliant life.

After the 1979 Revolution and the abdication of the Shah – the ‘King of Kings’ – the tune changed somewhat. Instead of looking to fair Puuushia and its poets, rock and rollers, by and large, drew inspiration from Ayatollah Khomeini and the nascent Islamic Republic. Take the Stranglers’ Shah Shah a Go Go (1979), for example, any one of the menacing tunes of the xenophobic Fearless Iranians from Hell from the 80s, or even Pedro Almodovar’s Iran-themed, rock and roll-flavoured Labyrinth of Passion (1982). In terms of the most iconic post-Revolution song, however, one would be hard-pressed to argue against the Clash’s Rock the Casbah (1982). On the surface, there’s absolutely nothing Iranian about Strummer’s invective: the ‘casbah’ and ‘shareef’ he screams about are Arabic words that invoke Algiers in North Africa more than faraway Tehran, while the well-known promo features a traditionally dressed Arab and Orthodox Jew getting up to no good. Unbeknownst to many, however, Strummer wrote the song in protest to Ayatollah Khomeini, who wasn’t the biggest fan of rock and roll. By order of the prophet, he cried, we ban that boogie sound! Strummer, perhaps, should have known better than to dish out such an Orientalist mashup; he had, after all, visited Iran as a child with his diplomat father.