As Placebo round up their world tour, we explore its frontman’s status as an LGBT icon

- TextTom Connick

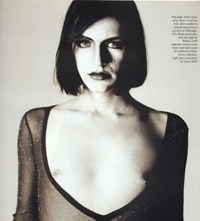

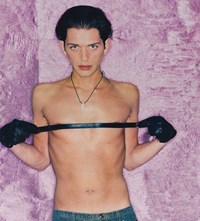

Emerging into a jack-the-lad 90s music scene dwarfed by Britpop’s posturing masculinity, Brian Molko was a breath of fresh air. A cross-dressing, unashamedly queer outlier in a world of boring, straight-as-an-arrow indie blokes, the Placebo frontman shook up the latter half of the decade, becoming a figurehead for outsiders everywhere in the process.

Wholeheartedly embracing their status as “a band for the outcasts, the misfits, the square pegs in the round holes”, as Molko put it in an Independent interview earlier this month, Placebo’s sentimentality and sexual honesty were interlinked – for every musical tale of drug-fuelled bedroom antics, there was another which explored emotional inner turmoil. For the first time in decades, there was a male icon who was both thoughtful and fuckable.

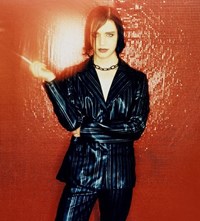

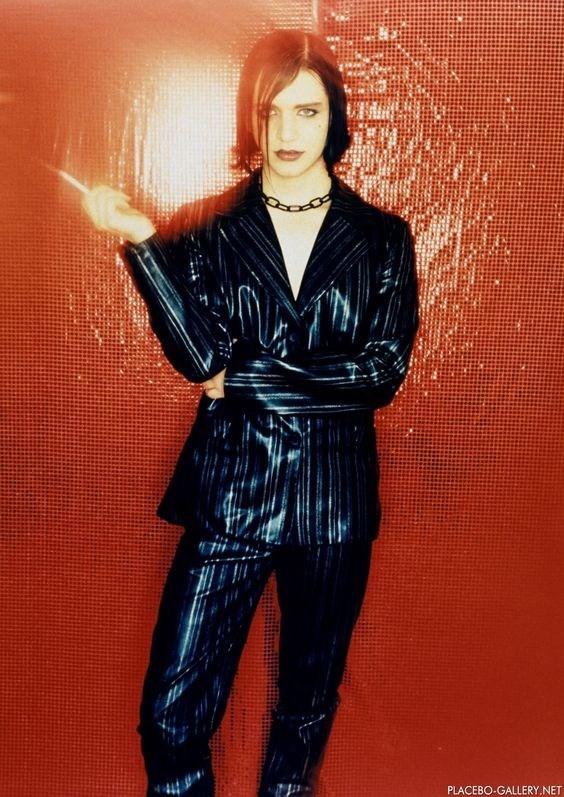

They jumped fences, rounding up the rock kids and the indieheads in equal measure, eschewing tribalism for a more thoughtful, inclusive approach to identity. From catwalks to club culture, Placebo’s seemingly subcultural movement soon impacted on the mainstream. Nancy Boy – a song which reclaimed sexual fluidity and promiscuity from the claws of negative, conservative discourse – leapt to the top of the charts, while the world of fashion practically plucked the clothes from Molko’s back, as designers across the globe attempted to ape his androgynous style. In a way not seen since their longtime inspiration and one-time collaborator David Bowie’s heyday, the weirdos ruled the roost.

Adamant that he was never out to invoke the kind of straight-up shock tactics that Marilyn Manson and other androgynous 90s stars relied on, Molko told Kerrang! this month that his cross-dressing was a largely political statement, aimed squarely at the homophobia that plagued in the music scene at the time. “Basically, I wanted anybody who was slightly homophobic in the audience to look at me and go, ‘ooh, she’s hot. I’d like to fuck her’,” he explained, “before realising that ‘her’ name was Brian, and then have to ask themselves a few questions about, shall we say, the fluidity of sexuality itself.” That fluidity was something Brian saw as inherent in modern sexuality. “For me, it’s not about gender – it’s about people,” he told the Belfast Telegraph of his own sexual attractions, emphasising the humanistic side to his politicised actions.

It’s a legacy that’s persisted through Britpop’s demise and indie’s changing fortunes – one which still pitches Placebo at the top of festival line-ups the world over, and pulls in crowds of thousands of disenfranchised, disillusioned individuals. 20 years on, they remain a force to be reckoned with, piledriving through convention, always one step ahead of societal norms. Flogging old clothing, equipment and rarities in a recent auction to raise funds for mental health charity CALM, a subsequent interview with NME saw Molko admit to his own struggles with depression, skewering mental health stigma in the same way he once tackled gender norms.

Taking to Brixton Academy stage this week to round up their ‘20 Years Of Placebo’ world tour, Molko’s victory lap was slightly tripped-up by a set of damaged vocal cords. While his sneering, acid-tongued vocals might have suffered, though, the group lost little of their combative power. The thunderous rhythm section, led by founding member Stefan Olsdal’s gut-rumbling basslines, saw Brixton’s balcony shudder, while a raw rendition of Without You I’m Nothing – backed by images of the late, great Bowie himself – found power in the wake of immense grief.

It’s that which is Placebo’s true masterstroke. For all their wilful gender fluidity, sexual politics and open-hearted sensuality, the way it’s delivered – cocksure, stomping, and with a snarl – continues to subvert still-existing preconceptions of what a ‘Nancy Boy’ can muster. As 5,000 black-clad fans roared their approval before spilling out into the streets of Brixton, another two decades at the top seem certain.