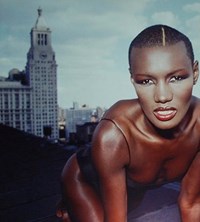

Grace Jones: Bloodlight and Bami, which hits cinemas tomorrow, shows many different facets of the Jamaican superstar

She was banned for life from Walt Disney World in Florida for exposing a breast mid-performance; she arrived late to a recording because she was torching then-boyfriend Dolph Lundgren’s trousers; and she rebuffed Lady Gaga’s invitation to collaborate, explaining she “just couldn’t find a soul” in there. With Grace Jones, the salacious stories just keep on coming, which makes it easy to write her off as a larger-than-life diva who’s spent four-plus decades courting controversy. But that would be a criminally poor estimation.

The fearless 69-year-old singer, subversive performance artist and all-around androgynous glamazon has been blazing trails since she first moved to Paris in 1970 to find work as a model. She was a muse to designer Jean Paul Gaultier and visual artist Jean-Paul Goude (with whom she had a son), a hedonistic disco diva, a badass Bond girl and a confidante to both Warhol and Haring. But those stories are out there for those looking to brush up on their 20th century pop culture history. In Sophie Fiennes’ intimate documentary portrait, Grace Jones: Bloodlight and Bami, which premiered last month at the Toronto International Film Festival, we skip the stale archive footage and are instead treated to a fascinatingly fragmented travelogue ten years in the making.

There are snippets of a Jones family trip back to Jamaica, time spent in the recording studio for her 2008 album Hurricane and a plethora of performances in Moscow, Tokyo, Paris and New York. Whether she’s drinking coconut water by a dirt track or indulging in a champagne breakfast wearing but a fur coat, Fiennes reveals the many faces of a woman who’s long-cultivated near-bulletproof mystique. In the lead-up to the film’s UK release, we list five facets of Jones on full display in Fiennes’ documentary portrait.

1. She only performs once you’ve paid her in full

“Sometimes, you have to be a high-flying bitch,” Jones sums up after a take-no-prisoners telephone meltdown in the documentary, paraphrasing the 1995 film Dolores Claiborne. She’s always been clear about only performing upon receipt of full payment – something electronics company LG clearly didn’t taken very seriously when they booked her for a London gig. Given these engagements serve to finance her own creative endeavours, she only commits to them once companies cough up the cash. Until then, they can beg all they want, as LG did, though the multinational’s whimpers fell on deaf ears.

2. She’s always meticulously curated her public image

Jones has long-exercised fierce control over all images and footage that go out into the world. While we’re treated to dazzling, carefully choreographed live musical numbers shot for the documentary – the kind Jones would approve, boasting white body paint, hula hoop twirls and Eiko Ishioka death masks – Bloodlight and Bami also finds her relinquishing some of that tightly guarded scrutiny to reveal a nurturing and vulnerable grandmother, daughter and ex-partner. “This has been a learning experience,” Jones suggested in Toronto. “Sometimes I feel like, ‘oh, my tummy is a bit fat there!’ It’s a good feeling to let that go, because I’m a prisoner of vanity. It has made me a stronger person, to look beyond this idea that everything has to be perfect.”

3. She channels past abuse into a commanding stage persona

A few telling scenes in Bloodlight and Bami find Jones applying make-up backstage, as a warrior would don her armour before heading out for battle. It brings to mind the collective trauma she and her siblings experienced at the hands of their grandmother’s violent, extremely Pentecostal husband, Mas P. As kids, they were treated to his sadistic beatings and humiliation back in Jamaica. Jones has now flipped that abuse and channelled it into her stage persona. She’d previously laid this out in her 2015 book I’ll Never Write My Memoirs, but it’s quite moving to hear the Jones clan share how they’ve transformed pain into fuel over the course of their adult lives.

4. Her mother was an incredible singer

Bloodlight and Bami is a family affair, notably through the presence of her son Paulo, his wife Azella and their daughter Athena. Sadly, since the film’s TIFF premiere, Jones’ mother Marjorie has passed away. The film showcases the incredible singer she was during a goosebumps-worthy church performance in Jamaica. And although Jones has her very legitimate reservations about the institution of Christian worship (see: #3), we see her fully own the part of ‘supportive daughter’, taking a few swigs of wine directly from the bottle in the backseat of a car before walking into the Lord’s house to cheer mum on.

5. She still gets asked to do incredibly tacky things

This won’t come as a surprise to many, but Jones has a Rolodex full of priceless, hilarious retorts for whenever someone crosses her. A French TV producer who tries to impose his tawdry, choreographed nightmare of lingerie-clad nymphets gyrating around Jones? “I look like the lesbian madam in a whorehouse!” she tells him incredulously. The film captures many such glimpses of Jones’ legendary sense of humour. Most of the time, she doesn’t even need to be riled up for the verbal bijoux to effortlessly roll off the tongue. Pointing to a serving of fresh oysters, she quips: “I wish my pussy was this tight.” God bless Grace Jones.

Grace Jones: Bloodlight and Bami has its UK premiere on 25 October at BFI Southbank. The documentary then opens in select theatres on 27 October.