Punk Troubles is a new book which explores the Northern Irish punk explosion during the 1970s

- TextTed Stansfield

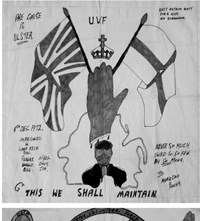

For many people in Northern Ireland, The Troubles are an all too fresh memory. The political conflict lasted three decades and its violence spilled over into the Republic of Ireland, the rest of the UK and even mainland Europe. In the mid-1970s however, punk provided a brief respite for young people growing up in this politically turbulent atmosphere. Catholics and Protestants came together under the banner of the anti-establishment movement, embracing its DIY ethic through music, clothing and writing.

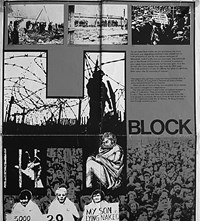

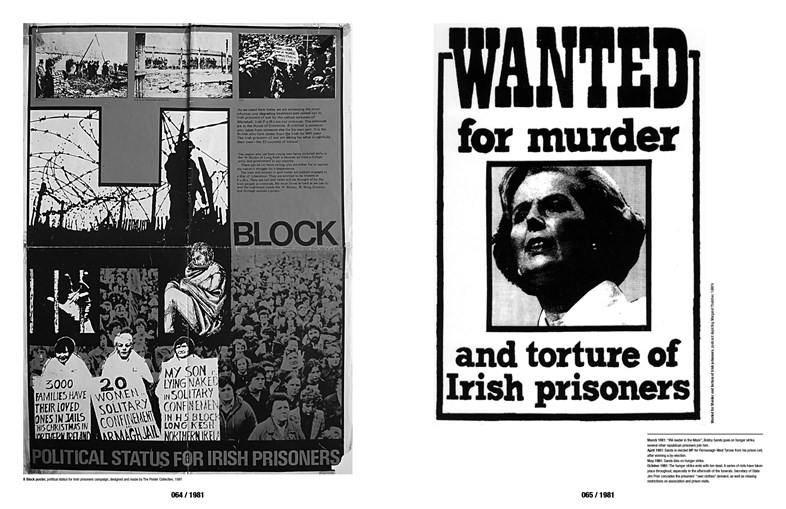

British artist and punk historian Toby Mott experienced this first-hand and has curated a new exhibition about it, together with the American Irish Historical Society and Dashwood Books. He’s created a book too, designed by Dazed’s art director Jamie Andrew Reid and previewed here, alongside an excerpt from a Q&A between Mott and Paul Burgess of Belfast band Ruefrex which was active at this time. Here, they discuss this era in Northern Irish history and the genesis of its punk explosion.

TOBY MOTT: Paul, could you tell me a little bit about the atmosphere of that time, 1977. You grew up in Belfast around the Shankill Road area which is notorious. Could you paint a visual picture for us?

PAUL BURGESS: Sure. Well I mean if you can imagine a Northern English town with the various brick back to backs, chimney stacks pushing out smoke, and I suppose the kind of social deprivation and poor public housing. Then superimpose a terrorist insurrection and, you know, effectively a war and the British Army on the streets, civic police force armed to the teeth. What else? I suppose curfews, searches going in and out of shops, regular indiscriminate bombing of commercial centres with associated random casualties. So it wasn’t great fun to be a teenager in and around that kind of thing.

TM: What age were you in 1977?

PB: I would’ve been 16/17 in 1977, perfect age for punk coming along.

TM: Which community were you a part of, reluctantly or not?

PB: Well I mean I was born into the Protestant community and people immediately make associations, outside Northern Ireland there’s immediately a catch-all designation. If you’re a Protestant you must be a loyalist and be a great supporter of a monarchy, and also be someone who broadly is supportive of Britain. You were expected to buy into all of that pretty unquestionably...

TM: But what would you say your identity is?

PB: Personally, I don’t accept the dichotomy that you’re either Irish or you’re British. I am Irish, I mean I come from Northern Ireland, it’s not rocket science. That said, because of the political reality that I was born into, my culture was a British one, and for a long time those two traditions and cultures were not mutually exclusive in the same way that being Scottish and British or being Welsh and British and so on would’ve been.

TM: Would you say that period in Belfast reflected the real punk backdrop, the clichés of urban decay, alienation and with the added sectarianism and a militarised state?

PB: It ticked all the boxes obviously. We were right in the middle of it at the time. You wouldn’t have had the objectivity to be able to step outside yourself and say ‘Hey, this is actually really quite cool from a sort of a let’s rise up and challenge the state or authority’. But of course, in Northern Ireland to challenge the state and to challenge authority had ramifications for the political situation you found yourself in. So you had this paradox, on the one hand wanting to be a teenager and kick against the man, but if you came from my community that would be seen as, you know, not to be standing up for your side, to being treasonous almost; so in a sense you weren’t allowed the luxury of that teenage rebellion. And punk did seem to give a voice to legitimizing an anti-authoritarian stance.

TM: Were you there at the genesis of the Northern Irish punk explosion?

PB: In as much as we would’ve been in the first phase of bands forming off the back of the news, the John Peel Show and the NME and the emerging theme that was coming about with The Clash and The Pistols and so on. So yeah, we would’ve been among the first to hear that clarion call and say hey, we can bring out fanzines, we can form a band, we can do all of these things, which was radical. I mean because up until that point, with the exception of Stiff Little Fingers, it’s not like we were already gigging in bands playing cover versions of Lynyrd Skynyrd or something which Fingers were of course were, famously with Highway Star. I think that’s a Deep Purple track, I can stand corrected on that but I think that’s where they took their name from.

Punk Troubles: Northern Island will be at American Irish Historical Society, 991 5th Ave, New York, September 21-October 13. Order a copy of the book here.