Following the appearance of a hand fan at the close of the Dior Men Pre-Fall 2020 show in Miami, Reiss Smith charts the history of the object – specifically its adoption by the LGBTQ community

- TextReiss Smith

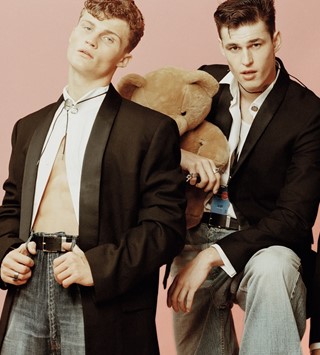

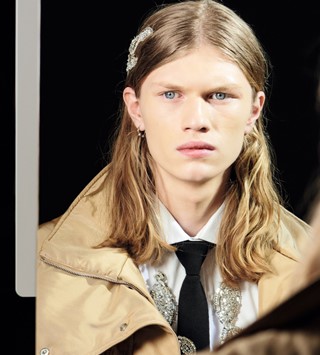

After the attention-grabbing collaborations with Shawn Stussy and Air Jordan, Dior’s Pre-Fall 2020 show ended with a quieter, but no less striking look. A white ‘Tailleur Oblique’ suit, lapel adorned with flowers, worn with a delicate silk and organza folding hand fan.

The fan is a curio plucked straight from the playbox of drag, much in the recent tradition of historically queer signifiers making their way into mainstream menswear. The most notable example of this phenomenon has been Louis Vuitton’s appropriation of the harness – a piece of bondage paraphernalia recast as luxury evening wear.

In the world of drag performance, the hand fan is a semaphore flag. “In contemporary drag it is used for punctuation,” says Joe E. Jeffreys, a drag historian and teacher at The New School and New York University. “The ‘clacking’ of a fan is a stylised auditory and visual form of underlining or exclamation. It signifies a robust style and a certain sassy attitude.”

Centuries before it was adopted by the LGBTQ community, the folding fan was the preserve of Japan’s aristocracy and Samurai classes. According to SOAS (School of Oriental and African Studies), the oldest surviving example dates back to 670 AD and was used not just for keeping cool, but for communicating court orders, maps and other important notations.

By the 15th century the fan had travelled along the Silk Road to Europe, and had reached the USA by the 19th century. In both cases, ornately embellished designs became a status symbol for women of high regard, and were reportedly used to convey secret messages (drawing the fan across the face was akin to saying “I love you,” Sotheby’s Alexandra Starp wrote in 2018).

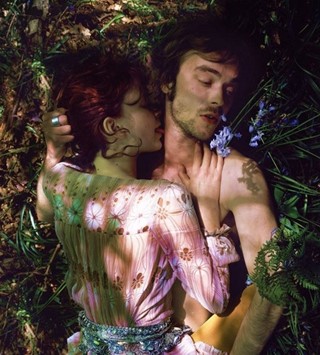

It’s difficult to pinpoint the fan’s assimilation into drag and queer culture. Decades before the advent of RuPaul’s Drag Race, fans were certainly part of the 1980s ballroom scene – the enclave of trans women and queer men of colour tenderly documented in Paris is Burning (1990) and more recently, the Ryan Murphy series Pose. Even more, they formed part of fanning, the dance which formed a sort of white counterpart to the voguing of the ballroom.

Candida Scott Piel, considered a mother of the fanning movement, said that the dance was popularised after a group of San Francisco men visited New York in the 1970s, There, they witnessed a troupe dancing with fans in a nightclub, and brought the idea back home with them. At first, these men would dance with cheap paper fans, but eventually they were replaced with softer fabric versions. It was highly stylised and flourished on both the east and west coasts, but was driven to near-extinction by the Aids crisis. Piel told the website Flagger Central that “so many fan players kept their cards close to their chests [that] when they died, they left no legacy”.

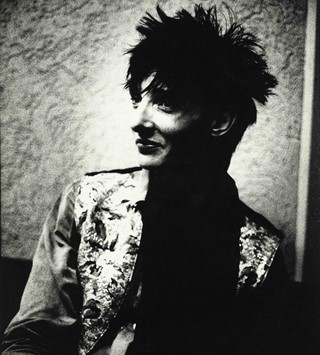

Pablo Solomon, a designer who has studied Asian art and social anthropology, and who has a lifelong involvement in art and dance, says that the use of hand fans by the LGBTQ community extends outside of performance. “In past times when homosexuality was not accepted in general society, it was not unusual for gay men from Europe and America to live and work in places like Morocco, Thailand, Vietnam, and China in order to follow their sexual inclinations,” he explains. “These countries derived a lot of their income from providing prostitutes – both male and female, and especially young – to foreigners.”

Solomon notes that the fan was “an item of flirtation”, used as a part of an “effeminate, seductive persona”. He offers as evidence: “The early movies of the 1930s and 40s often depicted expatriates living in exotic places, with those who were gay and perhaps shady stereotypically dressed in a kimono, with at least some make-up on and usually fan in hand.”

Dior said that its fan was inspired by classic French designs, an example of its atelier’s usual savoir faire. Whether the brand considered its other, historic connotations remains, at present, a mystery. But there’s no denying that it brought a certain queer appeal to the collection, one which is very much en vogue as wider conversations about gender expression continue apace. Jeffreys summarises this charm with a brief anecdote: “In my collection I have a vintage ‘Foldaway Fan’ box that notes the product ‘folds to fit your handbag’. It also states in big type on the side: ‘Keep Cool and Be Gay’. I think that sums it up perfectly.”