For a new generation of emerging designers, it seems that commerciality isn’t the priority, writes Rob Nowill

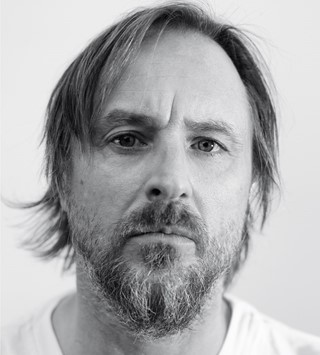

- TextRob Nowill

Has there ever been a worse time for a round of international fashion weeks? The stock market is coming out of its worst December since the Great Depression. Businesses from Asos to Apple are issuing profit warnings. And the Gilets Jaunes protests are winding down just weeks before fashion editors descend upon the city. The talk over Christmas dinners and New Year’s drinks has been about politics, the environment, the future. It’s hard to pivot back to thinking about trouser lengths.

It prompts the question, too, of exactly what the point of a fashion show is. There’s a fairly binary view of them, in general: depending on who you ask, they’re either a vital platform for creativity, or an example of capitalism’s worst excesses. On a fundamental level, of course, they’re a marketing platform for fashion designers. The brands show their wares to buyers and journalists (not to mention countless hangers-on), which means they sell more stuff.

But what about a fashion show that’s only showing things that can’t be produced or sold? And how about if what comes down the runway isn’t fashion at all? A fashion show without any fashion sounds like a contradiction in terms. Oddly, at the moment, it isn’t.

At the last round of men’s fashion shows in London, a duo of collections stood out. The MAN show – a presentation of a mixed group of emerging designers, sponsored by the organisation Fashion East – included two of the city’s most-discussed emerging names: Stefan Cooke and Rottingdean Bazaar. Both, to a greater or lesser extent, showed little in the way of wearable clothing, even by the outlandish standards of the typical runway show.

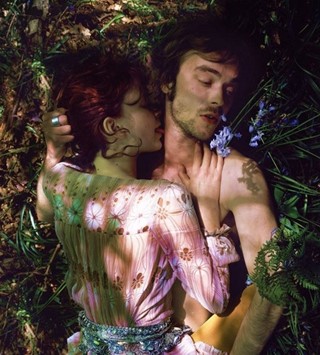

Rottingdean Bazaar (a label-slash-art-project-slash-in-joke by James Theseus Buck and Luke Brook) showed fancy dress costumes. Not fashion garments made to look like costumes. Actual pieces that were on loan from fancy dress stores (the models even carried placards listing the store that the pieces were borrowed from). It was head-scratching. If it was intended as a commentary, the designers weren’t saying on what: reviewers at the time were given little in the way of explanation, and the designers did not respond to an interview request for this piece.

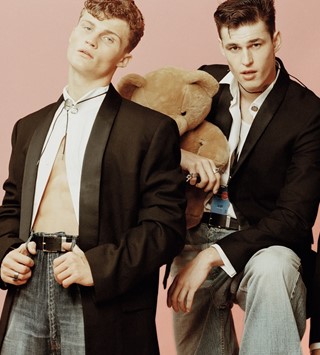

Stefan Cooke, meanwhile, showed garments made from over 7,000 buttons, strung together to create the illusion of argyle tops. The labour involved in their creation was astounding. In many ways, their work was the opposite of Rottingdean’s: crafted instead of sourced; sincere instead of ironic. But, undeniably, the pieces were just as impossible to mass-produce.

“The value of a piece of clothing from a luxury brand is different from one of our pieces: our focus is on new ideas, and expressing our point of view” – Stefan Cooke

The reaction was mixed. At the time, American Vogue praised the “humanity and humour” of both, while the Guardian called it “fun, funny, and riotous”. But others in the crowd groused that it their antics were juvenile, and attention-seeking, and gimmicky. What’s the point, they asked, in dragging a load half of the industry out – on a Saturday morning – to see clothes that can never be reproduced?

Cooke takes a different view. “Being a commercial brand depends how you look at it,” he says. “The value of a piece of clothing from a luxury brand is different from one of our pieces: our focus is on new ideas, and expressing our point of view.” Jake Burt, Cooke’s design partner, agrees: “We just loved the idea of the button pieces. So we did it, and it looked good. There’s value in that. And it’s better than selling a load of branded T-shirts.” Besides, Cooke is keen to point out that despite their inordinate workmanship (and, presumably, cost), he did receive private orders for his hand-made button pieces.

But it’s a stark contrast to London’s previous generation of emerging designers, who were notable for a preternatural sense of canny commerciality, even from the outset of their careers. When Grace Wales Bonner showed as part of Fashion East in 2015, her winningly wearable zip-through sweaters and high-rise jeans meant she was quickly picked up by retailers including Matchesfashion.com. Similarly, Craig Green may have been infamously mocked by David Gandy for the sculptural headpieces used in his first collection, but his workwear jackets and homely knits have become commercial dynamite. It’s hard to see how the new crop of designers will attract retailers so quickly.

But is that such a bad thing? One complaint that circulates increasingly around the fashion industry is the sense of a never-ending conveyor belt of ‘hot’ designers. Talents who have barely graduated from design school are being picked up and sold by international retailers before they have established design signatures, or the ability to produce their pieces at scale – and, too often, they burn out due to financial pressures, production problems, or simply by running out of good designs.

“There’s a lot of hype around being sellable. But I think it’s most the soulless part of the whole process. Whatever I make, even if it doesn’t sell, is valid” – Edwin Mohney

It’s something that even the retailers are acutely aware of. “What we want is ideas,” says Stavros Karelis, of the boutique Machine-A. “There will be time for the designers to commercialise their vision. I just want to see something different.” Damien Paul, head of menswear at Matchesfashion.com, agrees. “Because of social media, we’re increasingly seeing designers become starts overnight. I think the period of learning can be reduced, and that level of stardom can be difficult to sustain.” In essence: there’s a value in designers taking the time to experiment, to make mistakes, and to focus on what they find interesting (as opposed to what will sell, which is often a different thing entirely).

It can open other doors, too. Edwin Mohney, whose debut collection was shown six months earlier at the Central Martins MA show, showed models wearing inflatable swimming pools and rubber chickens. “It was fun to do absolutely whatever I wanted, and not really think at all about commercial viability,” he explains over the phone. His playful ideas and willingness to shock has led to commissions in costume design. And though his designs haven’t yet resonated commercially, he doesn’t care. “There’s a lot of hype around being sellable. But I think it’s most the soulless part of the whole process,” he reflects. “Whatever I make, even if it doesn’t sell, is valid.”

A confession: I was one of the editors who was left irritated by the MAN show. I left the venue muttering that I might as well have stayed home. But, six months on, Cooke’s work has stayed with me. It was thoughtful, and considered, and skilful. Even if it makes no money, there’s a value in that.